Córas na Poblachta (English: Republican System), a minor Irish republican political party, is founded on February 21, 1940.

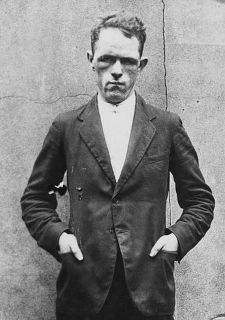

The idea for a new party is discussed at a meeting in Dublin on February 21, 1940, attended by 104 former officers of the pro- and anti-Treaty wings of the Irish Republican Army (IRA). The inaugural meeting of the new party takes place on March 2, 1940. Simon Donnelly, who had fought in Boland’s Mill under Éamon de Valera in the 1916 Easter Rising, the former leader of the Dublin section of the IRA, and former chief of the Irish Republican Police (IRP), is elected as president of a central committee of fifteen members. Other leaders are Seán Fitzpatrick, another Irish War of Independence veteran; Con Lehane, who had recently left the IRA; Séamus Gibbons; Tom O’Rourke; Seán Dowling, one of Rory O’Connor‘s principal lieutenants in the Irish Civil War; Colonel Roger McCorley, one of the principal IRA leaders in Belfast during the Irish War of Independence who had taken the Irish Free State side in the Irish Civil War; Frank Thornton, one of Michael Collins‘ top intelligence officers; Roger McHugh, a lecturer in English at University College Dublin (UCD) and later professor; Captain Martin Bell and Peter O’Connor.

Also in attendance at the first meeting is Seamus O’Donovan, Director of Chemicals on IRA Headquarters Staff in 1921 and architect of the IRA Sabotage Campaign in England by the IRA in 1939–40. Indeed, O’Donovan proposes several of the basic resolutions. Additionally, the meeting is attended by Eoin O’Duffy and several former leaders of the Irish Christian Front.

Many members of the Irish far-right join Córas na Poblachta including Gearóid Ó Cuinneagáin, who becomes the leader of the party’s youth wing Aicéin and goes on to found Ailtirí na hAiséirghe, Alexander McCabe, Maurice O’Connor and Reginald Eager from the Irish Friends of Germany, George Griffin, Patrick Moylett, his brother John and Joseph Andrews of the People’s National Party, Dermot Brennan of Saoirse Gaedheal, and Hugh O’Neill and Alexander Carey of Córas Gaedhealach. As a result, the party assumes a pro-German and antisemitic attitude which is frequently expressed in party functions, and Gardaí suspects Córas na Poblachta members of daubing the walls of Trinity College Dublin in antisemitic slogans following the visit of British politician Leslie Hore-Belisha to Ireland in 1941.

Socialist republicans Nora Connolly O’Brien and Helena Molony take an interest in the group. Reflecting divisions within the IRA, a minority of the party’s leaders sympathise with communism rather than fascism.

The main aim of Córas na Poblachta is the formal declaration of a Republic. It also demands that the Irish language be given greater prominence in street names, shop signs, and government documents and bank notes. It proposes to introduce national service in order that male citizens understand their responsibilities. The party’s economic policy is the statutory right to employment and a living wage. It proposes breaking the link with the British pound, the nationalisation of banks and the making of bank officials into civil servants. In the area of education, the party espouses free education for all children over primary age as a right, and university education when feasible. It also calls for the introduction of children’s allowances. In addition, Córas na Poblachta advocates for “the destruction of the Masonic Order in Ireland” and during its founding meeting reporters are told that the party will be ready to take over the government of Ireland “on either a corporate or fascist basis.”

The party has close ties with the Irish nationalist and pro-fascist party Ailtirí na hAiséirghe, whose leader, Gearóid Ó Cuinneagáin, had led Córas na Poblachta’s youth wing Aicéin until its independence is terminated in 1942. There is talk of a merger, however, while the majority of the party’s executive committee, noted by G2 to be made up of “four ex-Army men, old IRA, ex-Blueshirts and a number of IRA who had been active up until comparatively recently”, desires a combination of Ireland’s extreme nationalist movements, the three most prominent leaders, Simon Donnelly, Sean Dowling and Roger McCorley, oppose one due to the fear that the party will be submerged in a joint organisation. Ó Cuinneagáin is dismissive of Córas na Poblachta’s prospects and discussions between him and the party’s leaders reinforce their fears that Ó Cuinneagáin seeks an outright takeover by Ailtirí na hAiséirghe. Proposals for a merging of the two parties are dropped though they continue to maintain cordial relations and co-operate in the 1943 Irish general election.

The party is not successful and fails to take a seat in a by-election held shortly after the party’s foundation. The party slowly falls apart, and Tim Pat Coogan notes that: “Dissolution occurred because people tended to discuss the party rather than join it.” Importantly, the party is not supported by the hardcore of republican legitimatists, such as Brian O’Higgins, who views the IRA Army Council as the legitimate government of an existing Irish Republic. Indeed, in March 1940, O’Higgins publishes a pamphlet entitled Declare the Republic lambasting the new party as making what he regards as false promises that will be compromised on following the party’s election to the Oireachtas.

Córas na Poblachta fields candidates in the 1943 Irish General Election but none are elected, receiving a total of 3,892 votes between them.

Although a failure, Tim Pat Coogan argues Córas na Poblachta was the “nucleus” of the Clann na Poblachta party which emerges to help take power from Fianna Fáil in 1948.

(Pictured: IRA veteran Simon Donnelly who serves as President of Córas na Poblachta)