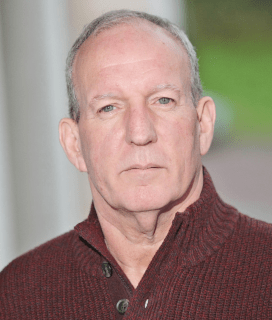

Robert “Bobby” Storey, a Provisional Irish Republican Army (IRA) volunteer, is born in Belfast, Northern Ireland, on April 11, 1956. Prior to an 18-year conviction for possessing a rifle, he also spends time on remand for a variety of charges and in total serves 20 years in prison. He also plays a key role in the Maze Prison escape, the biggest prison break in British penal history.

The family is originally from the Marrowbone area, on the Oldpark Road in North Belfast. The family has to move when Storey is very young due to Ulster loyalist attacks on the district, moving to Manor Street, an interface area also in North Belfast. His uncle is boxing trainer Gerry Storey and his father, also called Bobby, is involved in the defence of the area in the 1970s when Catholics are threatened by loyalists.

Storey is one of four children. He has two brothers, Seamus and Brian, and a sister Geraldine. Seamus and his father are arrested after a raid on their home which uncovers a rifle and a pistol. While his father is later released, Seamus is charged. He escapes from Crumlin Road Prison with eight other prisoners in 1971, and they are dubbed the Crumlin Kangaroos.

On his mother Peggy’s side of the family there is also a history of republicanism, but Storey says the dominant influences on him are the events happening around him. These include the McGurk’s Bar bombing in the New Lodge, some of those killed being people who knew his family, and also Bloody Sunday. This then leads to his attempts to join the IRA. He leaves school at fifteen and goes to work with his father selling fruit. At sixteen, he becomes a member of the IRA.

On April 11, 1973, his seventeenth birthday, Storey is interned and held at Long Kesh internment camp. He had been arrested 20 times prior to this but was too young for internment. In October 1974, he takes part in the protest at Long Kesh against living conditions where internees set fire to the “cages” in which they are being held. He is released from internment in May 1975. He is arrested on suspicion of a bombing at the Skyways Hotel in January 1976 and a kidnapping and murder in the Andersonstown district of Belfast in March 1976, but is acquitted by the judge at his trial. He is arrested leaving the courthouse and charged with a shooting-related incident. He is released after the case cannot be proven, only to be charged with shooting two soldiers in Turf Lodge. Those charges are dropped in December 1977. The same month he is arrested for the murder of a soldier in Turf Lodge, but the charges are again dropped. In 1978 he is charged in relation to the wounding of a soldier in Lenadoon, but is acquitted at trial due to errors in police procedure.

On December 14, 1979, he is arrested in Holland Park, London, with three other IRA volunteers including Gerard Tuite, and charged with conspiring to hijack a helicopter to help Brian Keenan escape from Brixton Prison. Tuite escapes from the same prison prior to the trial, and the other two IRA volunteers are convicted, but Storey is acquitted at the Old Bailey in April 1981. That August, after a soldier is shot, he is arrested in possession of a rifle and is convicted for the first time, being sentenced to eighteen years’ imprisonment.

Storey is one of the leaders of the Maze Prison escape in 1983, when 38 republican prisoners break out of the H-Blocks, the largest prison escape in British penal history and the largest peacetime prison escape in Europe. He is recaptured within an hour and sentenced to an additional seven years’ imprisonment. Released in 1994, he is again arrested in 1996 and charged with having personal information about a British Army soldier, and Brian Hutton, the Lord Chief Justice of Northern Ireland. At his trial at Crumlin Road Courthouse in July 1998, he is acquitted after his defence proves the personal information had previously been published in books and newspapers.

Having spent over twenty years in prison, much of it on remand, Storey’s final release is in 1998, and he again becomes involved in developing republican politics and strategy, eventually becoming the northern chairman of Sinn Féin.

On January 11, 2005, Ulster Unionist Member of Parliament for South Antrim David Burnside tells the British House of Commons under parliamentary privilege that Storey is head of intelligence for the IRA.

On September 9, 2015, Storey is arrested and held for two days in connection with the killing of former IRA volunteer Kevin McGuigan the previous month. He is subsequently released without any charges, and his solicitor John Finucane states Storey will be suing for unlawful arrest.

Storey dies in England on June 21, 2020, following an unsuccessful lung transplant surgery. Sinn Féin president Mary Lou McDonald describes him as “a great republican” in her tribute. His funeral procession in Belfast on June 30 is attended by over 1,500 people including McDonald, deputy First Minister Michelle O’Neill, and former Sinn Féin president Gerry Adams, but is criticised for breaking social distancing rules implemented in response to the COVID-19 pandemic which, at the time operating in Northern Ireland, limited funeral numbers to no more than 30 mourners.

In the 2017 film Maze, dramatising the 1983 prison break, directed by Stephen Burke, Storey is portrayed by Irish actor Cillian O’Sullivan.