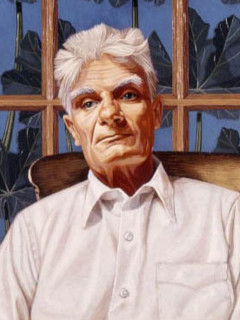

Sir John William Basil Kelly, Northern Irish barrister, judge and politician, is born in County Monaghan on May 10, 1920. He rises from poverty to become the last Attorney General of Northern Ireland and then one of the province’s most respected High Court judges. For 22 years he successfully conducts many of the most serious terrorist trials.

A farmer’s son, Kelly is raised amid the horror of the Irish Civil War. The family is burned out when he is five and, penniless, goes north to take a worker’s house near the Harland & Wolff shipyard in Belfast. Even though they are Protestant the Kellys are met with a cold welcome. To counter that, his mother starts a bakery while he and his father sell the hot rolls to the area pubs.

Kelly initially attends a shipyard workers’ school, sometimes without shoes, and then goes on to Methodist College Belfast, where only boys prepared to work hard are welcome. His mother, who had taught him to play the piano by marking out the keyboard on the kitchen table, is so cross when she hears that he has been playing football in the street that she tells the headmaster that he does not have enough homework.

On a visit to an elder sister at Trinity College, Dublin, Kelly is so impressed by her smoking and her painted nails that he decides to follow her to the university, where he reads legal science. After being called to the Bar of Northern Ireland in 1944, he has the usual slow start, traveling up to 100 miles to earn a five-guinea fee. However, aided by a photographic memory and the patronage of Catholic solicitors, he gradually builds up a large practice, concentrating on crime and workers’ compensation while earning a reputation as the finest cross-examiner in the province.

Kelly first makes a mark by his successful defence of an aircraftman accused of killing a judge’s daughter. The man is found guilty but insane, though the complications involved bring it back to court 20 years later. After appointment as Queen’s Counsel in 1958 he skillfully conducts two cases which go to the House of Lords. One involves the liability of a drunken psychopath, the other the question of automatism where a person, acting like a sleepwalker, does not know what he is doing.

In the hope of speeding his way to the Bench, Kelly is elected to the House of Commons of Northern Ireland as Ulster Unionist Party (UUP) member for Mid Down in 1964. His capacity for hard work leads to his being appointed Attorney General four years later.

In March 1972, the entire Government of Northern Ireland resigns, and the Parliament of Northern Ireland is prorogued. As a result, Kelly ceases to be Attorney General. The office of Attorney General for Northern Ireland is transferred to the Attorney General for England and Wales, and he is the last person to serve as Stormont’s Attorney General.

In 1973, Kelly is appointed as a judge of the High Court of Northern Ireland, and then as a Lord Justice of Appeal of Northern Ireland in 1984, when he is also knighted and appointed to the Privy Council of the United Kingdom. On the bench he proves a model of fairness and courtesy with a mastery of facts, but his role often puts him in danger.

A Provisional Irish Republican Army (IRA) gang once targets him with a bomb-laden milk van, intending to drive it through his gates. But the police are alerted and immediately take him to Stormont, where he lives for the next two months.

For a year Kelly presides alone over a non-jury Diplock court, protected by armed police and wearing a bulletproof vest before writing his judgment under Special Air Service (SAS) guard in England. He convicts dozens of people on “supergrass” evidence, though there are subsequently doubts about the informant and some of his judgments are overturned.

One of the accused, Kevin Mulgrew, is sentenced to 963 years in prison, with Kelly telling him, “I do not expect that any words of mine will ever raise in you a twinge of remorse.” While the IRA grumbles about the jail terms he dispenses, and he is often portrayed as an unthinking legal hardliner by Sinn Féin, he is a more subtle figure and is often merciful towards those caught up in events or those whom he considers too young for prison.

Kelly retires in 1995 and moves to England, where he dies at the age of 88 at his home in Berkshire on December 5, 2008, following a short illness. He is survived by his wife, Pamela Colmer.

(From: “Basil Kelly,” Independent.ie (www.independent.ie), January 4, 2009)