Evelyn Gleeson, English embroidery, carpet, and tapestry designer, dies at the age of 89 at Dun Emer, Dundrum, Dublin, on February 20, 1944. Along with Elizabeth and Lily Yeats, she establishes the Dun Emer Press.

Gleeson is born on May 15, 1855, in Knutsford, Cheshire, England, the daughter of Irish-born Edward Moloney Gleeson, a medical doctor, and Harriet (née Simpson), from Bolton, Lancashire. Her father has a practice in Knutsford but on a trip to Ireland he is struck by the poverty and unemployment and, with the advice of his brother-in-law, a textile manufacturer in Lancashire, he founds the Athlone Woollen Mills in 1859, investing all his money in the project. The family moves to Athlone in 1863, but Gleeson is educated in England, where she trains as a teacher. She later studies portraiture in London at the Atelier Ludovici from 1890–92. She goes on to study design with Alexander Millar, a follower of William Morris, who believes she has an exceptional aptitude for colour-blending. Many of her designs are bought by the exclusive Templeton Carpets of Glasgow.

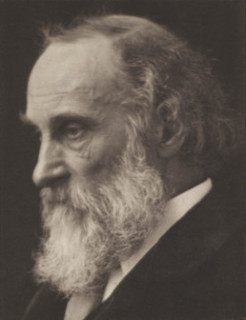

Gleeson takes a keen interest in Irish affairs and, as a member of the Gaelic League and the Irish Literary Society, mixes with the Yeats family and the Irish artistic circle in London and is inspired by the Gaelic revival in art and literature. She is also involved in the suffrage movement and is chairwoman of the Pioneer Club, a women’s club in London. In 1900, an opportunity arises to make a practical contribution to the Irish renaissance and the emancipation of Irish women. She is suffering from ill-health, but her friend Augustine Henry, botanist and linguist, suggests she move away from the London smog to Ireland and open a craft centre with his financial assistance. She seizes the opportunity and discusses her plans with her friends the Yeats sisters, Elizabeth and Lily, who are talented craftswomen and have direct contact with William Morris and his followers. They have no money to contribute to the venture but are enthusiastic and can offer their skills and provide contacts. She seeks advice from W. B. and Jack Yeats, from Henry, who loans her £500, and from her cousin, T. P. Gill, secretary of the Department of Agriculture and Technical Instruction.

During the summer of 1902 Gleeson finds a suitable house in Dundrum, County Dublin, ten minutes from the railway station. The house, originally called Runnymede, is renamed Dun Emer, after the wife of Cú-Chulainn, renowned for her craft skills. The printing press arrives in November 1902, and soon three craft industries are in operation. Lily Yeats runs the embroidery section, since she had trained with Morris’s daughter May. Elizabeth Yeats operates the press, having learned printing at the Women’s Printing Society in London. Gleeson manages the weaving and tapestry and looks after the financial affairs of the industries. W. B. Yeats acts as literary adviser, an arrangement that often causes friction, and Gleeson’s sister, Constance McCormack, is also involved.

Local girls are employed and trained, and the industries seek to use the best of Irish materials to make beautiful, high-quality, lasting products of original design. Church patronage accounts for most of their orders and, in 1902–03, Loughrea cathedral commissions twenty-four embroidered banners portraying Irish saints. They also make vestments, traditional dresses, drapes, cushions and other items, all beautifully crafted and mostly employing Celtic design. The first book published is In the Seven Woods (1903), by W. B. Yeats, cased in full Irish linen.

Gleeson is in demand as an adjudicator in craft competitions around the country and at Feis na nGleann in 1904 she praises the workmanship of the entries but is critical of the lack of teaching in design. She gives lectures and tries to raise the status of craftwork from household occupation to competitive industry. There are tensions with the Yeats sisters, who complain that she is bad-tempered and arrogant. In truth she had taken on too much of a financial burden, even with the support of grants, and she is anxious to repay her debt to Augustine Henry, which he is prepared to forego. The sisters snub her and omit her name in an interview about Dun Emer in the magazine House Beautiful. Millar, her design teacher in London, likens the omission to Hamlet without the prince. In 1904, it is decided to split the industries on a cooperative basis: Dun Emer Guild Ltd. under Gleeson and Dun Emer Industries Ltd. under the Yeats sisters.

Work continues, and the guild and industries exhibit separately at the Royal Dublin Society (RDS) and other craft competitions. In 1907, the National Museum of Ireland commissions a copy of a Flemish tapestry. It takes far longer than anticipated to complete, but the result is beautiful and is exhibited at the Arts and Crafts Society of Ireland in 1910. The guild wins a silver medal at the Milan International exhibition in 1906. The guild and industries both show work at the New York exhibition of 1908. The guild alone shows work in Boston. By now cooperation has turned to rivalry, and there is a final split as the Yeats sisters leave, taking the printing press with them to their house in Churchtown, Dublin. Gleeson writes off a debt of £185 owed to her, on condition that they do not use the name Dun Emer.

The business thrives at Dundrum, with her niece Katherine (Kitty) MacCormack and Augustine Henry’s niece, May Kerley, assisting with design. Later they move the workshops to Hardwicke Street, Dublin. In 1909, Gleeson becomes one of the first members of the Guild of Irish Art Workers and is made master in 1917. The Irish Women Workers’ Union commissions a banner from her about 1919, and, among numerous other notable successes, a Dun Emer carpet is presented to Pope Pius XI in 1932, the year of the Eucharistic Congress of Dublin.

Gleeson dies at the age of 89 at Dun Emer, Dundrum, Dublin, on February 20, 1944, with Kitty carrying on the Guild after her death. The final home of Dun Emer is a shop on Harcourt Street, Dublin, which finally closes in 1964.

(From: “Gleeson, Evelyn” by Ruth Devine, Dictionary of Irish Biography, http://www.dib.ie, October 2009)