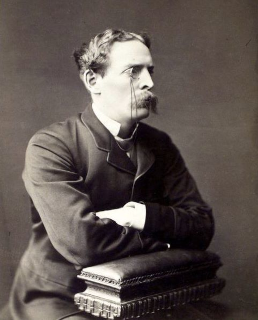

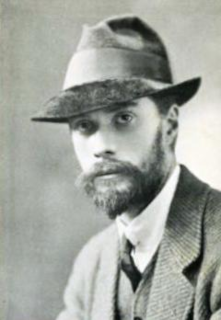

Edward Neil Anthony Hannon, Northern Irish singer and songwriter, is born in Derry, County Londonderry, on November 7, 1970. He is the creator and front man of the chamber pop group The Divine Comedy, and is the band’s sole constant member. He is the writer of the theme tunes for the television sitcoms Father Ted and The IT Crowd.

Hannon is the son of Brian Hannon, a Church of Ireland minister in the Diocese of Derry and Raphoe and later Bishop of Clogher. He spends some of his youth in Fivemiletown, County Tyrone, before moving with his family to Enniskillen, County Fermanagh, in 1982. While there he attends Portora Royal School.

Hannon enjoys synthesizer-based music as a youngster. He identifies The Human League and Orchestral Manoeuvres in the Dark (OMD) as “the first music that really excited [him].” In the late 1980s he develops a fondness of the electric guitar, becoming an “indie kid.”

Hannon is founder and mainstay of The Divine Comedy, a band which achieves their biggest commercial success in the last half of the 1990s with the albums Casanova (1996), A Short Album About Love (1997), and Fin de Siècle (1998). He continues to release albums under The Divine Comedy name, the most recent being Office Politics (2019). In 2000 he and Joby Talbot contribute four tracks for Ute Lemper‘s collaboration album, Punishing Kiss.

In 2004 Hannon plays alongside the Ulster Orchestra for the opening event of the Belfast Festival at Queen’s University Belfast. In 2005, he contributes vocals to his long-time collaborator Joby Talbot’s soundtrack for the movie version of The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy.

In 2006 it is announced that Hannon is to lend his vocal ability to the Doctor Who soundtrack CD release, recording two songs – “Love Don’t Roam” for the 2006 Christmas special, “The Runaway Bride“, and a new version of “Song For Ten”, originally used in 2005’s “The Christmas Invasion.” On January 12, 2007, The Guardian website’s “Media Monkey” diary column reports that Doctor Who fans from the discussion forum on the fan website Outpost Gallifrey are attempting to organise mass downloads of the Hannon-sung “Love Don’t Roam,” which is available as a single release on the UK iTunes Store. This is in order to attempt to exploit the new UK Singles Chart download rules, and get the song featured in the Top 40 releases.

The same year Hannon adds his writing and vocal talents to the Air album Pocket Symphony, released in the United States on March 6, 2007. He is featured on the track “Somewhere Between Waking and Sleeping,” for which he writes the lyrics. This song had been originally written for and sung by Charlotte Gainsbourg on her album, 5:55. Though it is not included in its 2006 European release, it is added as a bonus track for its American release on April 24, 2007.

Hannon wins the 2007 Choice Music Prize for his 2006 album, Victory for the Comic Muse. He wins the 2015 Legend Award from the Oh Yeah organisation in Belfast.

Hannon is credited with composing the theme music for the sitcoms Father Ted and The IT Crowd, the former theme composed for the show and later reworked into “Songs of Love,” a track on The Divine Comedy’s breakthrough album Casanova. Both shows are created or co-created by Graham Linehan. A new Divine Comedy album, Bang Goes the Knighthood, is released in May 2010.

Hannon has collaborated with Thomas Walsh, from the Irish band Pugwash, to create a cricket-themed pop album under the name The Duckworth Lewis Method. The first single, “The Age of Revolution,” is released in June 2009, and a full-length album is released the following week. The group’s second album, Sticky Wickets, comes out in 2013.

Hannon contributes to a musical version of Swallows and Amazons, writing the music while Helen Edmundson writes the book and lyrics, which premiers in December 2010 at the Bristol Old Vic.

In April 2012 Hannon’s first opera commission, Sevastopol, is performed by the Royal Opera House. It is part of a program called OperaShots, which invites musicians not typically working within the opera medium to create an opera. Sevastopol is based upon Leo Tolstoy‘s Sevastopol Sketches. Hannon’s second opera for which he writes music, In May, premiers in May 2013 in Lancaster and is shown in 2014 with overwhelming success.

The world premiere of “To Our Fathers in Distress,” a piece for organ, is performed on March 22, 2014, in London, at the Royal Festival Hall. It is inspired by Hannon’s father, Rt. Revz. Brian Hannon, who suffers from Alzheimer’s disease.

Hannon’s partner is Irish musician Cathy Davey. The couple live in the Dublin area. He is previously married to Orla Little, with whom he has a daughter, Willow Hannon. With Davey, Hannon is a patron of the Irish animal charity My Lovely Horse Rescue, named after the Father Ted Eurovision song for which he wrote the music.

Politically, Hannon describes himself as being “a thoroughly leftie, Guardian-reading chap, but of the champagne socialist variety.”