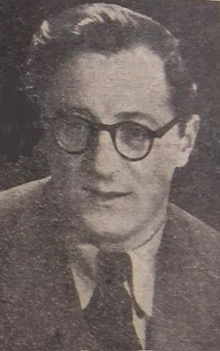

Gearóid Seán Caoimhín Ó Cuinneagáin, political activist and publisher, is born John Gerald Cunningham in Belfast on January 2, 1910.

Ó Cuinneagáin Is the third child of Sean Cunningham and his wife Caitlín. He is educated in Belfast, at St. Brigid’s school, Malone Road, and the St. Patrick’s Christian Brothers school on Donegall Street. His political views are permanently influenced by memories of the sectarian violence of 1920–22. In 1927, he enters the Irish civil service as a tax clerk, stationed first at Athlone and then at Castlebar. He is promoted to junior executive officer in the Department of Defence, but resigns in July 1932 after his superiors refuse to allow him six months unpaid leave to study the Irish language in the Donegal Gaeltacht. He turns down a promotion to the Department of Finance, a decision partly motivated by disillusion with Fianna Fáil. He subsequently works as an accountant and lives in the south Dublin suburbs. In 1934, he establishes his own publishing company, Nuachtáin Teoranta, which he boasts is the first company to be registered in the Irish language, and he also contributes to an Irish language socialist paper, An t-Éireannach, under the pen name “Bruinneal gan Smal.”

In 1940–41, Ó Cuinneagáin is active in the Friends of Germany, a pro-Nazi organisation which disintegrates after some of its leading members are interned. On September 26, 1940, he founds Craobh na h-Aiséirighe, a branch of the Gaelic League aimed at attracting dynamic young enthusiasts frustrated by the older activists who dominate established branches. It makes a point of using modern publicity methods to get its message across, a trait which is carried over into Ailtirí na hAiséirghe (Architects of Resurrection), a political movement made up of branch members, which Ó Cuinneagáin founds in 1942. This move leads to the expulsion of Craobh na h-Aiséirighe from the Gaelic League and the establishment of Glún na Buaidhe by branch members who disapprove of his political ambitions and wish to concentrate on the promotion of the Irish language.

Members of Ailtirí wear an informal uniform of a green shirt, tweed suit, and báinín jacket. In private Ó Cuinneagáin reveals that the organisation is modeled on the Hitler Youth. His own title of “ceannaire” (leader) equates with “Führer” and “duce.” Features of the movement copied from Nazism include an emphasis on propaganda based on a few simple concepts and phrases. The claim that party politics allow statesmen to evade individual responsibility, whereas a single leader is necessarily more responsive to public opinion; and the belief that all difficulties can be overcome through willpower.

Ó Cuinneagáin takes to extremes contemporary Catholic advocacy of a corporate state based on vocational principles as the solution to the problems of modernity. While venerating António de Oliveira Salazar‘s Portugal as a role model, he believes that Ireland can surpass it and create a Catholic social model that will redeem the whole world. He takes a quasi-racial view of Irishness and comes close to saying that the only true Irish Catholics are of Gaelic race. When Seán Ó’Faoláin comments acidly in The Bell on the paradox of “Celtophiles” who bear such Celtic names as Blackham and Cunningham, Ó Cuinneagáin protests that he can prove his pure Gaelic descent. The Ailtirí state forces all male citizens to undertake a year’s compulsory military service, which is also used as a means of Gaelicisation, and the resulting citizen army of 250,000 would mount a lightning invasion of Northern Ireland, modeled on the blitzkrieg, with a favourite slogan being “Six Counties, Six Divisions, Sixty Minutes.” In 1943, the Stormont government excludes Ó Cuinneagáin from Northern Ireland.

Ailtirí attracts considerable attention. Its leaders address numerous meetings around the country, attracting large crowds to demonstrations at Dublin and Cork. Ó Cuinneagáin, who is by no means unintelligent, is capable of shrewd observations on the restrictions imposed on most Irish-language bodies by government subsidies, and the impact of the snobbery shown toward the poor by their middle class co-religionists. Several of his lieutenants are academics or engineers. In the 1970s he praises modernist architecture as breaking with the hated Georgian past, and denounces conservationists who oppose plans to build an oil refinery in Dublin Bay. Bilingual pamphlets produced by the group sell thousands of copies. Ó Cuinneagáin is the author of several, including Ireland’s twentieth century destiny (1942), Aiséirí says . . .(1943), Partition: a positive policy (1945), and Aiséirí for the worker (1947). Hus attempts to launch a party paper are stifled until the end of the war. Some of the interest attracted by the group is derived from curiosity or amusement. It also functions to some extent as a front organisation for the banned Irish Republican Army (IRA), with Ó Cuinneagáin declaring that Jews and freemasons should be locked up instead of IRA men. Aiséirí members are involved in the bombing of the Gough memorial in Phoenix Park in July 1957, with the stolen head concealed for a time in the party’s offices.

The party runs four candidates, including Ó Cuinneagáin in Dublin North-West, in the 1943 Irish general election and seven in 1944, but all lose their deposits. Ó Cuinneagáin does not actually vote for himself. Throughout his life he demands Irish language ballot papers. When given English language ones he tears them up, claiming that they disenfranchise him and that this invalidates the election. In 1946, Ailtirí na h-Aiséirí elects eight members to local bodies in counties Louth and Cork. This helps to bring about the decline of the party, as the Cork activists rebell against the rigid Führerprinzip upheld by the electorally unsuccessful ceannaire and his Dublin acolytes. Most of the party’s local support is absorbed by Clann na Poblachta. Ó Cuinneagáin retains a small group of followers centred on his newspaper Aiséirighe.

Ó Cuinneagáin keeps himself in the public gaze by driving around the country in a van painted with slogans, and by regularly appearing in court for refusing to respond to official documents (rates demands, car insurance, court summonses) unless they are supplied in Irish. He enjoys some success in securing the provision of Irish language versions of such documents, and he contrasts the state’s niggardliness on this point with its professed commitment to the revival of Irish. In 1954, he founds an Irish language women’s artistic and social paper, Deirdre, which operates successfully for over a decade without government subsidy.

Ó Cuinneagáin continues to write sympathetically about IRA activities, at one point offering a £1,000 reward for the capture of the Prime Minister of Northern Ireland, Basil Brooke. He maintains surprisingly extensive international neo-fascist contacts. He regularly reprints in Aiséirighe material by the American antisemite and racial segregationist Gerald L. K. Smith. He cites praise for Aiséirighe from Der Stahlhelm, a far-right German veterans’ paper, and notes Oswald Mosley‘s support for Irish reunification. He denounces Hugh Trevor-Roper‘s Last days of Hitler as typical British slander of a fallen enemy. He compares the sacrificial ideology of the Hungarian Nazi collaborator Ferenc Szálasi to that of Patrick Pearse. He praises Juan Perón as a model whom Ireland should imitate and he follows the electoral fortunes of Italian neo-fascism with interest. He also maintains contacts with the radical right-wing fringes of Breton, Scottish, and Welsh nationalism. He declares that Ireland’s grievance is against England alone and bemoans the Dublin government’s failure to encourage the break-up of the United Kingdom.

Ó Cuinneagáin denounces the Soviet Union and United States alike as controlled by Zionists and freemasons. He points to illegitimacy and divorce rates in the United States as proof of the folly of those who regard “progressive” American education as superior to the sound Irish teaching methods embodied by the Christian Brothers, and bemoans the increasing flow of “immoral” American comics and paperback books into Ireland. While noting with pride that he has been described as “Ireland’s foremost Jew-baiter,” He claims that his frequent diatribes against Robert Briscoe and the state of Israel are merely anti-Zionist, and that he has nothing against Jews, whom he defines as ultra-Orthodox anti-Zionists. He hopes that a Europe united on national–Christian principles might fend off the influence of the super powers. He echoes Mosleyite calls for European unity and is an early and determined advocate of Irish membership of the European Community. However, he dissents from the Mosleyite view that such a union should be based on African empire. He is generally anti-imperialist, though somewhat more lenient toward Portuguese than British imperialism, and from 1956 the President of Egypt, Gamal Abdel Nasser, becomes one of his heroes. While supporting European unity as a defensive strategy, he also warns that unless Ireland adopts mass conscription the country might be conquered by a regiment of Russian paratroopers landing on Dollymount Strand. Throughout the 1950s and 1960s he regularly calls for the Irish Army to mount a military coup, hinting that it should install him as leader in the same way that the Portuguese army had installed Salazar.

Ó Cuinneagáin gives up contesting elections but regularly cites those who do not vote in elections as indicating the extent of political support for Ailtirí na hAiséirghe. He regularly laments that the safety valve of emigration had taken the steam out of radical politics. In his later years he notes the growth of anti-clericalism and the beginnings of a permissive society in Dublin. He attributes this to the church’s failure to implement its own social teaching and its encouragement of West British snobbery at the expense of the truly Catholic traditions of the Gael.

On April 4, 1945, Ó Cuinneagáin marries Sile Ní Chochláin. They have four sons and two daughters, some of whom become active in left-wing politics. He dies on June 13, 1991. He tends to be remembered as a figure of fun, but this view demands some qualification. He possesses genuine abilities and dedication. His fantasies are an extreme development of the official ideology of the state, and part of his appeal stems from his ability to point out the hypocrisy involved in paying it lip service while failing to push it to its logical conclusion. The blindness and cruelty involved in imposing his world view at a personal level has their counterparts in the institutions of official Ireland. Ailtirí na hAiséirghe may have been a marginal millennial cult, but in Europe during the 1940s such groups were often raised to power by circumstances. Had the World War II taken a different direction after 1940, he might be remembered not as a parody of Pearse but as an Irish Szálasi.

(From: “Ó Cuinneagáin, Gearóid Seán Caoimhín” by Patrick Maume, Dictionary of Irish Biography, http://www.dib.e, October 2009)