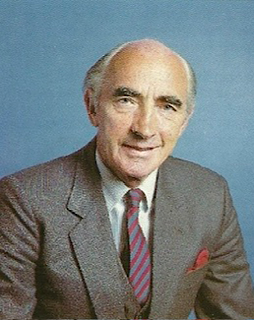

Michael J. Browne, an Irish prelate of the Roman Catholic Church, dies in Galway, County Galway, on February 24, 1980. He serves as Bishop of Galway and Kilmacduagh for almost forty years from 1937 to 1976.

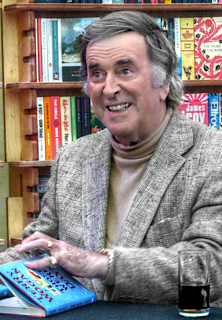

Browne is born in Westport, County Mayo, on December 20, 1895. He is an important and outspoken member of the Irish hierarchy. His time as Bishop has been described by the historian James S. Donnelly Jr. as “far-reaching and … controversial,” while the historian of Irish Catholicism John Henry Whyte claims that Browne’s “readiness to put forward his views bluntly is welcome at least to the historian.”

Browne is ordained to the priesthood on June 20, 1920, for the Archdiocese of Tuam. He later serves as professor of moral theology at St. Patrick’s College, Maynooth.

On August 6, 1937, at the relatively young age of 41, Browne is appointed Bishop of Galway and Kilmacduagh by Pope Pius XI, receiving his episcopal consecration from Archbishop Thomas Gilmartin on the following August 10. He supports Taoiseach Éamon de Valera‘s defence of arrests and police searches for cached Irish Republican Army (IRA) arms, declaring, “Any Irishman who assists any foreign power to attack the legitimate authority of his own land is guilty of the most terrible crime against God’s law, and there can be no excuse for that crime – not even the pretext of solving partition or of securing unity.”

In 1939, Browne is selected by Éamon de Valera to chair the Commission on Vocational Organisation.

Browne is attentive to the state of public morality in the diocese, and James S. Donnelly Jr. has noted his role in directing episcopal and clerical censorship of newsagents and county librarians. He is also concerned about public intoxication and other misconduct at the Galway Races, controversies over dancing and the commercial dance halls, as well as immodesty in dress and the closely related issue of so-called “mixed bathing” in Galway and Salthill.

Like other members of the Irish Catholic hierarchy, Browne regularly condemns communism in his pastoral letters. When Cardinal József Mindszenty is detained by Hungary‘s post-war communist government, Browne in 1949 forwards protest resolutions from Galway Corporation, Galway County Council and the University College Galway student body to Pope Pius XII. He also frequently condemns the Connolly Association, an Irish republican socialist group in Britain close to the Communist Party of Great Britain.

In 1957, in response to a growing tension between Catholics and Protestants at Fethard-on-Sea, including the Fethard-on-Sea boycott, Browne says, “non-Catholics do not protest against the crime of conspiring to steal the children of a Catholic father, but they try to make political capital when a Catholic people make a peaceful and moderate protest.”

The most enduring monument or physical legacy of Browne’s time as Bishop is the Cathedral of Our Lady Assumed into Heaven and St Nicholas, commonly known as Galway Cathedral, which is dedicated in 1965 by Cardinal Richard James Cushing of Boston, Massachusetts. The site of the old jail had come into the possession of the diocese in 1941 and Browne leads the campaign to construct a new Cathedral. This includes a 1957 audience with Pope Pius XII where the plans are approved.

Browne attends the Second Vatican Council from 1962 to 1965 and retires in 1976. He dies four years later in Galway, at the age of 84, on February 24, 1980.

Browne is parodied in Breandán Ó hÉithir`s novel Lig Sinn i gCathu, which fictionalises late 1940s Galway as “Baile an Chaisil” and Browne as “An tEaspag Ó Maoláin.”

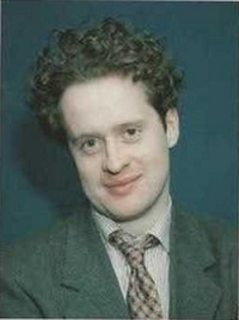

The Irish cabinet minister Noël Browne (no known relation) in his 1986 memoir Against the Tide describes the physical attributes of his episcopal namesake:

“The bishop had a round soft baby face with shimmering clear cornflower-blue eyes, but his mouth was small and mean. Around his great neck was an elegant glinting gold episcopal chain with a simple pectoral gold cross. He wore a ruby ring on his plump finger and wore a slightly ridiculous tiny scullcap on his noble head. The well-filled semi-circular scarlet silk cummerbund and sash neatly divided the lordly prince into two.”