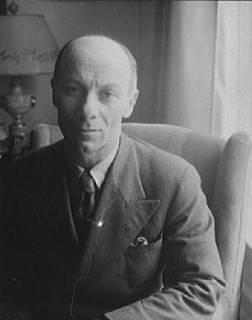

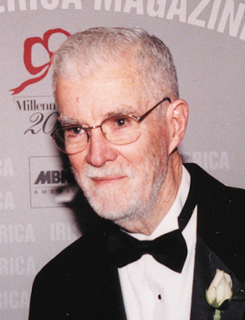

Eoin McKiernan, early scholar in the interdisciplinary field of Irish Studies in the United States and the founder of the Irish American Cultural Institute (IACI), dies in Saint Paul, Minnesota on July 18, 2004. He is credited with leading efforts to revive and preserve Irish culture and language in the United States.

Born John Thomas McKiernan in New York City on May 10, 1915, McKiernan adopts the old Irish form of his name, Eoin, early in his life. While in college, he wins a scholarship to study Irish language in the Connemara Gaeltacht in the west of Ireland. In 1938, he marries Jeannette O’Callaghan, whom he met while studying Irish at the Gaelic Society in New York City. They raise nine children.

McKiernan attends seminary at Cathedral College of the Immaculate Conception and St. Joseph’s College in New York, leaving before ordination. He earns degrees in English and Classical Languages (AB, St. Joseph College, NY, 1948), Education and Psychology (EdM, UNH, 1951), and American Literature and Psychology (PhD, Penn State, 1957). Later in life, he is awarded honorary doctorates from the National University of Ireland, Dublin (1969), the College of Saint Rose, Albany (1984), Marist College, Poughkeepsie (1987) and the University of St. Thomas, Saint Paul (1996).

Passion for Irish culture is the dominant undercurrent of a distinguished teaching career in secondary (Pittsfield, NH, 1947–49) and university levels (State University of New York at Geneseo, 1949–59, and University of St. Thomas in Saint Paul, MN, 1959–72). McKiernan serves as an officer of the National Council of College Teachers of English, is appointed by the Governor of New York to a State Advisory Committee to improve teacher certification standards and serves as a Consultant to the U.S. Department of Education in the early 1960s.

McKiernan suggests to the Irish government in 1938 that a cultural presence in the United States would promote a deeper understanding between the two countries, but he eventually realises that if this is to happen, he will have to lead the way. His opportunity comes in 1962, when he is asked to present a series on public television. Entitled “Ireland Rediscovered,” the series is so popular that another, longer series, “Irish Diary,” is commissioned. Both series air nationwide. The enthusiastic response provides the impetus to establish the Irish American Cultural Institute (IACI) in 1962. In 1972 he resigns from teaching to devote his energy entirely to the IACI.

Under McKiernan’s direction, the IACI publishes the scholarly journal Eire-Ireland, with subscribers in 25 countries, and the informational bi-monthly publication Ducas. The IACI still sponsors the Irish Way (an immersion program for U.S. teenagers), several speaker series, a reforestation program in Ireland (Trees for Ireland), theatre events in both countries and educational tours in Ireland. He continues these educational Ireland tours well into his retirement. At his suggestion, the Institute finances the world premiere of A. J. Potter‘s Symphony No. 2 in Springfield, Massachusetts.

Troubled by the biased reporting of events in Northern Ireland in the 1970s, McKiernan establishes an Irish News Service, giving Irish media and public figures direct access to American outlets. In the 1990s, he is invited by the Ditchley Foundation to be part of discussions aimed at bringing peace to that troubled area and is a participant in a three-day 1992 conference in London dealing with civil rights in Northern Ireland. Organized by Liberty, a London civil rights group, the conference is also attended by United Nations, European Economic Community, and Helsinki representatives.

McKiernan also founds Irish Books and Media, which is for forty years the largest distributor of Irish printed materials in the United States. In his eighth decade, he establishes Irish Educational Services, which funds children’s TV programs in Irish and provided monies for Irish language schools in Northern Ireland. Irish America magazine twice names him one of the Irish Americans of the year. In 1999, they choose him as one of the greatest Irish Americans of the 20th century.

McKiernan dies on July 18, 2004, in Saint Paul, Minnesota. On his death, The Irish Times refers to him as the “U.S. Champion of Irish culture and history . . . a patriarch of Irish Studies in the U.S. who laid the ground for the explosion of interest in Irish arts in recent years.”

On July 14, 1999,

On July 14, 1999,

The first recorded “

The first recorded “