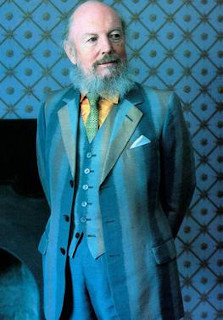

Garech Domnagh Browne, art collector and notable patron of Irish arts and traditional Irish music, is born in Chapelizod, Dublin on June 25, 1939. He is often known by the Irish designation of his name, Garech de Brún, or alternatively Garech a Brún, especially in Ireland.

Browne is the eldest of the three sons of Dominick Browne, 4th Baron Oranmore and Browne and his second wife, Oonagh Guinness, daughter of Arthur Ernest Guinness and wealthy heiress to the Guinness fortune. His father has the rare distinction of sitting in the House of Lords for 72 years, until his death at the age of 100 in August 2002, without ever speaking in a debate.

As both his parents are married three times, Browne has two stepmothers and two stepfathers, as well as a number of older half-siblings. His only full brother, Tara Browne, is a young London socialite whose death at the age of 21 in a car crash in London’s West End helps inspire John Lennon when writing the song “A Day in the Life” with Paul McCartney. Browne is educated at Institut Le Rosey, Switzerland. Although a member of the extended Guinness family, he takes no active part in its brewing business.

When in Ireland, Browne lives at Luggala, set deep in the Wicklow Mountains in County Wicklow. The house, which he inherited from his mother, has been variously described as a castle or hunting lodge of large proportions. He once states he would rather have not been born, calling it “frightful to bring anyone into this world.”

Browne is a leading proponent for the revival and preservation of traditional Irish music through his record label Claddagh Records which he founds with others in 1959. His former home, Woodtown Manor near Dublin, is for many years a welcoming place for Irish poets, writers and musicians. The folk-pop group Clannad makes many recordings of their music there.

Browne is instrumental in the formation of the traditional Irish folk group The Chieftains. In 1962, after setting up Claddagh Records, he asks his friend, the famed uileann piper Paddy Moloney, to form a group for a one-off album. Moloney responds with the first line-up for the band, which goes on to achieve international commercial success.

Browne is interviewed at length for the Grace Notes traditional music programme on RTÉ lyric fm on 18 March 2010. He is a friend and patron of British artist Francis Bacon and in January 2017 is featured in the BBC documentary Francis Bacon: A Brush with Violence.

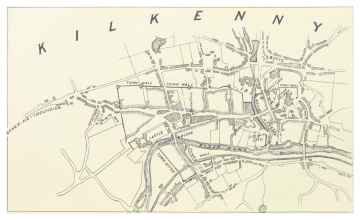

Garech Browne dies at the age of 78 in London on March 10, 2018. In his will and testament, he bequeaths to the city of Galway the granite remains of a medieval “bow gate.” The location of this gate, which had otherwise gone unmentioned by Browne, remains a mystery for over a year following his death. It is discovered on the grounds of the Luggala estate in 2019. According to a Galway historian, the gate may have formed part of the city’s defences in the 17th century, and was later removed from the city by Browne’s father, when it was probably taken to the Browne family home at Castle MacGarrett, just outside Claremorris in County Mayo. The gate is one of a number of items left to the Irish State by Browne.