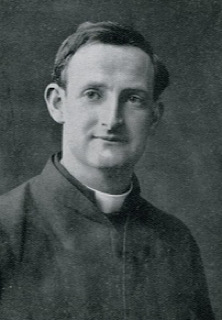

William Joseph Gabriel Doyle, SJ, MC, an Irish Catholic priest, is born in Dalkey, County Dublin, on March 3, 1873. He is killed in action while serving as a military chaplain to the Royal Dublin Fusiliers during the World War I. He is a candidate for sainthood in the Catholic Church.

Doyle is the youngest of seven children of Hugh and Christine Doyle (née Byrne). He is educated at Ratcliffe College, a Catholic boarding school in Leicester, England.

After reading St. Alphonsus‘ book Instructions and Consideration on the Religious State, he is inspired to enter the priesthood. In March 1891, he enters the Society of Jesus (Jesuits) in Ireland. He then enters St. Stanislaus College in Tullabeg, Rahan, County Offaly. Having completed his novitiate, for his regency he is assigned to teach. He teaches at Belvedere College, Dublin, and at Clongowes Wood College, County Kildare, between 1894 and 1898. He then studies philosophy at Collège Saint-Augustin in Enghien, Belgium, and Stonyhurst College, England. From 1904 to 1907, he studies theology at Milltown College and University College Dublin (UCD).

He was ordained a Catholic priest on July 28, 1907. He then undertakes his tertianship at Drongen Abbey, Drongen, Belgium. He takes his final vows on February 2, 1909. From 1909 until 1915 he serves on the Jesuit mission team, traveling around Ireland and Britain preaching parish missions and conducting retreats. In 1914 he is involved in the foundation of a Colettine Poor Clares monastery in Cork, County Cork. He is an early member of the Pioneer Total Abstinence Association and is considered a future leader of the organisation by its founder, Fr. James Cullen.

Doyle volunteers to serve in the Royal Army Chaplains’ Department of the British Army during World War I. He is appointed as a chaplain with the 16th (Irish) Division. He is assigned to the 8th Battalion, Royal Irish Fusiliers, and is posted with them to the Western Front. During the Battle of Loos he is caught in a German gas attack and for his conduct is mentioned in dispatches. A recommendation for a Military Cross is rejected as “he had not been long enough at the front.” He is presented with the “parchment of merit” of the 49th (Irish) Brigade instead. On August 16, 1917, he is killed in action at the Battle of Langemarck “while administering the last rites to his stricken countrymen.”

Doyle is awarded the Military Cross for his bravery during the assault on the village of Ginchy during the Battle of the Somme in 1916. He is also posthumously recommended for both the Victoria Cross and the Distinguished Service Order, but is awarded neither. It is possible that anti-Catholicism played a role in the British Army’s decision not to grant him both awards.

General William Hickie, the commander-in-chief of the 16th (Irish) Division, describes Father Doyle as “one of the bravest men who fought or served out here.”

Doyle’s body is never recovered but he is commemorated at Tyne Cot Commonwealth War Graves Cemetery and Memorial to the Missing in the Ypres Salient on the Western Front.

Doyle is proposed for canonisation in 1938, but this is not followed through. His papers can be found in the Jesuit archives, Leeson Street, Dublin.

A stained glass window dedicated to Doyle’s memory is present in St. Finnian’s Church, Dromin, County Louth.

Despite his troubled relationship with the Catholic Church in Ireland, Irish author and playwright Brendan Behan is known to have always felt a great admiration for Doyle. He praises Doyle in his 1958 memoir Borstal Boy. Alfred O’Rahilly‘s biography of the fallen chaplain is known to have been one of Behan’s favorite books.

Irish folk singer Willie ‘Liam’ Clancy is named after Doyle due to his mother’s fondness for him, although they never meet.

In August 2022, the Father Willie Doyle Association is established to petition the Catholic Church to introduce a cause for canonisation for Doyle. In January 2022, the Supplex Libellus, the formal petition, is presented to Bishop Thomas Deenihan. Having consulted with the Irish Bishops’ Conference and the Dicastery for the Causes of Saints, Deenihan issues an edict on October 27, 2022, announcing the opening of a cause. The Opening Session takes place on November 20, 2022, at the Cathedral of Christ the King, Mullingar.