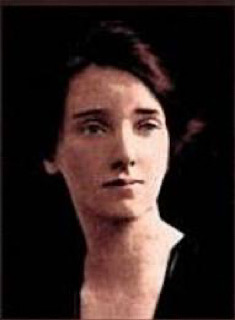

Dorothy Macardle, Irish writer, novelist, playwright, journalist and non-academic historian, dies in Drogheda, County Louth, on December 23, 1958. Associated throughout her life with Irish republicanism, she is a founding member of Fianna Fáil in 1926 and is considered to be closely aligned with Éamon de Valera until her death, although she is vocal critic of how women are represented in the 1937 constitution created by Fianna Fáil. She is also unable to respect de Valera’s attitudes adopted during World War II. Her book, The Irish Republic, is one of the more frequently cited narrative accounts of the Irish War of Independence and its aftermath, particularly for its exposition of the anti-treaty viewpoint.

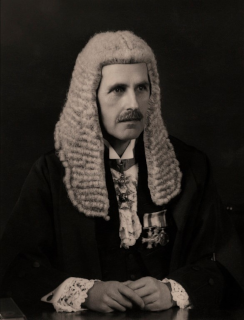

Macardle is born in Dundalk, County Louth, on March 7, 1889, into a wealthy brewing family famous for producing Macardle’s Ale. Her father, Sir Thomas Callan Macardle, is a Catholic who supports John Redmond and the Irish Home Rule movement, while her mother, Lucy “Minnie” Macardle, comes from an English Anglican background and is politically a unionist. Lucy converts to Catholicism upon her marriage to Thomas. Macardle and her siblings are raised as Catholics, but Lucy, who is politically isolated in Ireland, “inculcated in her children an idealised view of England and an enthusiasm for the British empire“. She receives her secondary education in Alexandra College, Dublin—a school under the management of the Church of Ireland—and later attends University College Dublin (UCD). Upon graduating, she returns to teach English at Alexandra where she had first encountered Irish nationalism as a student. This is further developed by her first experiences of Dublin’s slums, which “convinced her that an autonomous Ireland might be better able to look after its own affairs” than the Dublin Castle administration could.

Between 1914 and 1916, Macardle lives and works in Stratford-upon-Avon in Warwickshire, England. There, her encounters with upper-class English people who express anti-Irish sentiment and support keeping Ireland in the British Empire by force further weakens her Anglophilia. Upon the outbreak of World War I, she supports the Allies, as does the rest of her family. Her father leads the County Louth recruiting committee while two of her brothers volunteer for the British Army. Her brother, Lieutenant Kenneth Callan Macardle, is killed at the Battle of the Somme, while another brother, Major John Ross Macardle, survives the war and earns the Military Cross. While Macardle is a student, the Easter Rising occurs, an experience credited for a further divergence of her views regarding republicanism and her family.

Macardle is a member of the Gaelic League and later joins both Sinn Féin and Cumann na mBan in 1917. In 1918, she is arrested by the Royal Irish Constabulary (RIC) while teaching at Alexandra.

On January 19, 1919, Macardle is in the public gallery for the inaugural meeting of the First Dáil and witnesses it declare unilateral independence from the United Kingdom, which is ultimately the catalyst for the Irish War of Independence.

By 1919 Macardle has befriended Maud Gonne MacBride, the widow of the 1916 Easter Rising participant John MacBride, and together the two work at the Irish White Cross, attending to those injured in the war. It is during this period she also becomes a propagandist for the nationalist side.

In December 1920, Macardle travel to London to meet with Margot Asquith, the wife of the former British prime minister H. H. Asquith, hoping to establish a line of communication between the Irish and British governments. It is during this trip that she comes into contact with Charlotte Despard, sister of the Lord Lieutenant of Ireland John French. Despard takes the pro-Irish side in the war and returns with Macardle to Dublin.

Following the signing of the Anglo-Irish Treaty in December 1921, Macardle takes the anti-treaty side in the ensuing Irish Civil War. Alongside Gonne MacBride and Despard, she helps found the Women Prisoners’ Defence League, which campaigns and advocates for republicans imprisoned by the newly established Irish Free State government. It is also during this same time that she begins working alongside Erskine Childers in writing for anti-treaty publications An Phoblacht and Irish Freedom.

In October 1922, Despard, Gonne MacBride and Macardle are speaking at a protest on O’Connell Street, Dublin against the arrest of Mary MacSwiney, a sitting Teachta Dála, by the Free State when Free State authorities move to break it up. Rioting follows and Free State forces open fire, resulting in 14 people being seriously wounded while hundreds of others are harmed in the subsequent stampede to flee. Following the event, Macardle announces she is going to pursue support of the Anti-treaty side full-time in a letter to Alexandra College, which ultimately leads to her dismissal on November 15, 1922. In the following days Macardle is captured and imprisoned by the Free State government and subsequently serves time in both Mountjoy Prison and Kilmainham Gaol, with Rosamond Jacob as her cellmate. During one point at her time in Kilmainham, Macardle is beaten unconscious by male wardens. She becomes close friends with Jacob and shares a flat with her in Rathmines later in the 1920s.

The Irish Civil War concludes in the spring of 1923, and Macardle is released from prison on May 9.

Following the Irish Civil War, Macardle remains active in Sinn Féin and is drawn into the camp of its leader Éamon de Valera and his wife Sinéad. She travels alongside the de Valeras as they tour the country and she is a frequent visitor to their home. As the trust between Macardle and de Valera develops, de Valera asks her to travel to County Kerry to investigate and document what later becomes known as the Ballyseedy massacre of March 1923, in which a number of unarmed republican prisoners are reportedly killed in reprisals. She obliges, and by May 1924 she has compiled a report that is released under the title of The Tragedies of Kerry.” Immediately upon the release of the report, the Minister for Defence Richard Mulcahy sets up an inquiry in June 1924 to carry out a separate investigation by the government. However, the government’s inquiry comes to the conclusion there had been no wrongdoing committed. Her book The Tragedies of Kerry remains in print and is the first journalistic historical account of the Irish Civil War from those on the republican side detailing Ballyseedy, Countess Bridge and various other incidents that occur in Kerry during this time.

In 1926, Éamon de Valera resigns as President of Sinn Féin and walks out of the party following a vote against his motion that members of the party should end their policy of abstentionism against Dáil Éireann. De Valera and his supporters, including Macardle, form the new political party Fianna Fáil in May 1926, with Macardle immediately elected to the party’s National Executive|Ard Chomhairle, one of six female members out of twelve on the original party National Executive, the others being Hanna Sheehy-Skeffington, Kathleen Clarke, Countess Constance Markievicz and Linda Kearns. Macardle is made the party’s director of publicity. However, she resigns from Fianna Fáil in 1927 when the new party endorses taking their seats in Dáil Eireann. Nevertheless, her views remain relatively pro-Fianna Fáil and pro-de Valera.

Macardle recounts her civil war experiences in Earthbound: Nine Stories of Ireland (1924). She continues as a playwright for the next two decades. In her dramatic writing, she uses the pseudonym Margaret Callan. In many of her plays a domineering female character is always present. This is thought to be symbolic of her own relationship with her own mother. Her parents’ marriage had broken up as her mother returned to England and her father raised the children with servants in Cambrickville and they were sent away for school. This female character holds back the growth and development of the younger female character in Dorothy’s plays and writings.

By 1931, Macardle takes up work as a writer for The Irish Press, which is owned by de Valera and leans heavily toward supporting Fianna Fáil and Irish republicanism in general. In addition to being a theatre and literary critic for the paper, she also occasionally writes pieces of investigative journalism such as reports on Dublin’s slums. In the mid-1930s she also becomes a broadcaster for the newly created national radio station Radio Éireann.

In 1937, Macardle writes and publishes the work by which she is best known, The Irish Republic, an in-depth account of the history of Ireland between 1919 until 1923. Because of the book, political opponents and some modern historians consider her to have been a hagiographer toward de Valera’s political views. In 1939 she admits, “I am a propagandist, unrepentant and unashamed.” Overall, however, the book is well-received, with reviews ranging from “glowing” to measured praise. She is widely praised for her research, thorough documentation, range of sources and narration of dramatic events, alongside reservations about the book’s political slant. The book is reprinted several times, most recently in 2005. Éamon de Valera considers The Irish Republic the only authoritative account of the period from 1916 to 1926, and the book is widely used by de Valera and Fianna Fáil over the years and by history and political students. She spends seven years writing the book in a cottage in Delgany, County Wicklow, and it is a day-by-day account of the history of the events in Ireland from 1919 to 1923 recorded in painstaking detail together with voluminous source material.

In 1937, de Valera’s Fianna Fáil government is able to create a new Constitution of Ireland following a successful referendum. However, there is widespread criticism of the new Constitution from women, particularly republican women, as the language of the new Constitution emphasises that a woman’s place should be in the home. Macardle is among them, deploring what she sees as the reduced status of women in this new Constitution. Furthermore, she notes that the new Constitution drops the commitment of the 1916 Proclamation of the Irish Republic to guarantee equal rights and opportunities “without distinction of sex” and writes to de Valera questioning how anyone “with advanced views on the rights of women” can support it. DeValera also finds her criticising compulsory Irish language teaching in schools.

The entire matter of the new Constitution leads Macardle to join Hanna Sheehy-Skeffington’s Women’s Social and Progressive League.

While working as a journalist with the League of Nations in the late 1930s, Macardle acquires a considerable affinity with the plight of Czechoslovakia being pressed to make territorial concessions to Nazi Germany. Believing that “Hitler‘s war should be everybody’s war,” she disagrees with de Valera’s policy of neutrality. She goes to work for the BBC in London, develops her fiction and, in the war’s aftermath, campaigns for refugee children – a crisis described in her book Children of Europe (1949). In 1951, she becomes the first president of the Irish Society of Civil Liberties.

Macardle dies of cancer on December 23, 1958, in a hospital in Drogheda, at the age of 69. Though she is somewhat disillusioned with the new Irish State, she leaves the royalties from The Irish Republic to her close friend Éamon de Valera, who had written the foreword to the book. De Valera visits her when she is dying. She is accorded a state funeral, with de Valera giving the oration. She is buried in Sutton, Dublin.