Columba (or Colum Cille), Irish abbot and missionary evangelist credited with spreading Christianity in what is today Scotland at the start of the Hiberno-Scottish mission., dies on June 9, 597.

He is born into the Cenél Conaill, a branch of the Northern Uí Néill, then Ireland’s most powerful dynasty. His place of birth is reputedly Gartan in modern day County Donegal, though there is no contemporary evidence for this.

His is the son of Fedlimid, who is said to be a great-grandson of Niall Nóigiallach, and his wife Eithne. The Irish form of his name, Colum Cille, has been taken to mean ‘Dove of the Church’. He is fostered and baptised by a priest named Cruithnechán, who lives near his birthplace. It is reputed that he undergoes schooling in bardic studies. His biographer, Adomnán (c. 624–704), states that he receives monastic training under a bishop whom he names variously as Findbarr or Finnio, who can most likely be identified as Finnian of Movilla. Otherwise little is known of his early life.

Adomnán states that Columba leaves Ireland in his forty-second year. Later tradition records that his departure is an act of penitence for instigating the battle of Cúl Dreimhne in 561, supposedly because he surreptitiously copies a Psalter lent to him by his former master, Finnian. Adomnán simply states, however, that he leaves Ireland to become a “pilgrim for Christ.” He probably also wishes to sever himself from the secular concerns arising from his family connections. Whatever the reason, he remains in Scotland for the rest of his life, returning to Ireland only on a few occasions.

His choice of Iona, an island off the Ross of Mull on the western coast of Scotland, as a monastic refuge is influenced by the contacts that his family has with the kingdom of Dál Riata and its rulers. Certainly it is under Dál Riata patronage that he subsequently founds the island monasteries of Campus Lunge (on Tiree) and Hinba, which more recent opinion takes to have been the island of Colonsay. He also founds churches in Inverness, probably following on his meeting with and likely conversion of Bridei I, king of the Picts. All of Iona’s foundations, on both sides of the Irish Sea, are under the headship of the abbot of the mother-house, and many of the abbots of the most important houses of the paruchia of Iona are of Columba’s kin-group. Although many foundations elsewhere in Scotland and in Northumbria are later attributed to him, it is doubtful whether Iona evangelises outside of Ireland, Dál Riata and Pictland. Yet there can be no doubt of his political influence. He “ordains” Áedán king of Dál Riata, and his influence and connections enable him to strengthen the alliance between the Uí Néill and Dál Riata.

One of the few, if not the only, times he leaves Scotland is toward the end of his life, when he returns to Ireland to found the monastery at Durrow.

According to traditional sources, Columba dies in Iona on Sunday, June 9, 597, and is buried by his monks in the abbey he created. However, Dr. Daniel P. McCarthy disputes this and assigns a date of 593 to Columba’s death. The Annals record the first raid made upon Iona in 795, with further raids occurring in 802, 806 and 825. Columba’s relics are finally removed in 849 and divided between Scotland and Ireland.

Colmcille is one of the three patron saints of Ireland, after Patrick and Brigid of Kildare. He is the patron saint of the city of Derry, where he founded a monastic settlement in c. 540. The Catholic Church of Saint Colmcille’s Long Tower, and the Church of Ireland St. Augustine’s Church both claim to stand at the spot of this original settlement. The Church of Ireland Cathedral, St. Columb’s Cathedral, and the largest park in the city, St. Columb’s Park, are named in his honour. The Catholic Boys’ Grammar School, St. Columb’s College, has him as Patron and namesake.

St. Columba’s National School in Drumcondra is a girls’ school named after the saint.

St. Colmcille’s Primary School and St. Colmcille’s Community School are two schools in Knocklyon, Dublin, named after him, with the former having an annual day dedicated to the saint on June 9.

The town of Swords, Dublin is reputedly founded by Colmcille in 560 AD. St. Colmcille’s Boys’ National School and St. Colmcille’s Girls’ National School, both located in the town of Swords, are also named after the Saint as is one of the local Gaelic teams, Naomh Colmcille.

The Columba Press, a religious and spiritual book company based in Dublin, is named after Colmcille.

Aer Lingus, Ireland’s national flag carrier has named one of its Airbus A330 aircraft in commemoration of the saint (reg: EI-DUO).

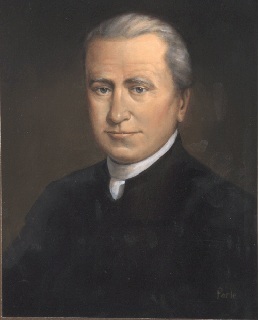

(Pictured: Columba banging on the gate of Bridei, son of Maelchon, King of Fortriu)