Constance Markievicz, while detained in Holloway Prison for her part in conscription activities, becomes the first woman to be elected to the House of Commons of the United Kingdom on December 28, 1918.

Markievicz, an Irish nationalist, who is elected for the Dublin St. Patrick’s constituency, refuses to take her seat in the House of Commons along with 72 other Sinn Féin MPs. Instead, her party, which wins the majority of Irish seats in Westminster, establishes the Dáil, a breakaway Dublin assembly, and triggers the Irish War of Independence.

Markievicz, who inherits the title of “countess” from her noble Polish husband, and 45 other MPs are in jail when the first meeting takes place on January 21, 1919. They are described in Gaelic as being “imprisoned by the foreign enemy” when their names are read out during roll call at the Mansion House.

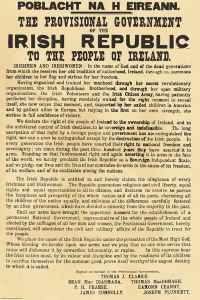

The 27 MPs who attend the Dáil’s first session ratify the Proclamation of the Irish Republic of Easter 1916, which had not been adopted by an elected body but merely by the Easter rebels claiming to act in the name of the Irish people. They also claim there is an “existing state of war, between Ireland and England” in a Message to the Free Nations of the World.

When Markievicz is released in April 1919, she becomes Minister for Labour. Having also been part of the suffragette movement, her deep political convictions contrast deeply with Nancy Astor, Viscountess Astor, the first woman to sit in the House of Commons. She believes Astor, a Tory who is elected in a 1919 Plymouth by-election after her husband is forced to give up the seat when he becomes a peer, is “out of touch.”

Her political views are also influenced by Irish poet William Butler Yeats, who is a regular visitor to the family home, Lissadell House in County Sligo. She becomes involved in the women’s suffrage movement after studying art in London, where she meets and marries Count Casimir Markievicz. In 1903, the couple, who has one son, settles in Dublin, where she becomes involved in nationalist politics. She joins both Sinn Féin and Inghinidhe na hÉireann.

Like Astor, Markievicz has an irrepressible personality and is in no mood to play coy and simply blend in. She comes to her first Sinn Féin meeting wearing a satin ball-gown and a diamond tiara after attending a function at Dublin Castle, the seat of British rule in Ireland.

Markievicz spends a year in the Dáil before walking out along with Éamon de Valera, the future dominant figure in Irish politics, after opposing the Anglo-Irish Treaty. The document, which grants southern Ireland independence but keeps the north as part of the UK, splits Sinn Féin and triggers the Irish War of Independence.

Following the conflict, which the Pro-Treaty forces win, Markievicz is elected again to the Dáil, but does not take her seat in protest. In 1927, she is elected for a third time as part of de Valera’s new party Fianna Fáil, which pledges to return to the Irish parliament. But before she can take her seat, she dies at age 59 on July 15, 1927, of complications related to appendicitis.