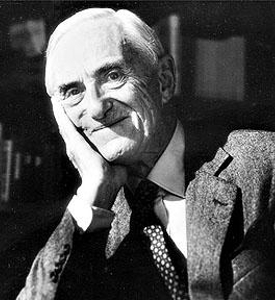

James Kennedy, a Northern Irish songwriter and lyricist, dies in Cheltenham, Gloucestershire, England on April 6, 1984. In a career spanning more than fifty years, he writes some 2,000 songs, of which over 200 become worldwide hits and about 50 are all-time popular music classics. Until the duo of John Lennon and Paul McCartney, Kennedy has more hits in the United States than any other Irish or British songwriter.

Kennedy is born near Omagh, County Tyrone, Northern Ireland. His father, Joseph Hamilton Kennedy, is a policeman in the Royal Irish Constabulary, which exists before the partition of Ireland. While growing up in Coagh, Kennedy writes several songs and poems. He is inspired by local surroundings such as the view of the Ballinderry river, the local Springhill house and the plentiful chestnut trees on his family’s property, as evidenced in his poem Chestnut Trees. Kennedy later moves to Portstewart, a seaside resort.

Kennedy graduates from Trinity College, Dublin, before teaching in England. He is accepted into the Colonial Service, as a civil servant, in 1927.

While awaiting a Colonial Service posting to the colony of Nigeria, Kennedy embarks on a career in songwriting. His first success comes in 1930 with The Barmaid’s Song, sung by Gracie Fields. Fellow lyricist Harry Castling introduces him to Bert Feldman, a music publisher based in London‘s “Tin Pan Alley,” for whom Kennedy starts to work. In the early 1930s he writes a number of successful songs, including Oh, Donna Clara (1930), My Song Goes Round the World (1931), and The Teddy Bears’ Picnic (1933), in which he provides new lyrics to John Walter Bratton‘s tune from 1907.

In 1934, Feldman turns down Kennedy’s song Isle of Capri, but it becomes a major hit for a new publisher, Peter Maurice. He writes several more successful songs for Maurice, including Red Sails in the Sunset (1935), inspired by beautiful summer evenings in Portstewart, Northern Ireland, Harbor Lights (1937) and South of the Border (1939), inspired by a holiday picture postcard he receives from Tijuana, Mexico, and written with composer Michael Carr. Kennedy and Carr also collaborate on several West End theatre shows in the 1930s, including London Rhapsody (1937). My Prayer, with original music by Georges Boulanger, has English lyrics penned by Kennedy in 1939. It is originally written by Boulanger with the title Avant de Mourir in 1926.

During the early stages of World War II, while serving in the British Army‘s Royal Artillery, where he rises to the rank of Captain, Kennedy writes the wartime hit, We’re Going to Hang out the Washing on the Siegfried Line. His hits also include Cokey Cokey (1945), and the English lyrics to Lili Marlene. After the end of the war, his songs include Apple Blossom Wedding (1947), Istanbul (Not Constantinople) (1953), and Love Is Like a Violin (1960). In the 1960s he writes the song The Banks of the Erne, for recording by his friend from the war years, Theo Hyde, also known as Ray Warren.

Kennedy is a patron of the Castlebar International Song Contest from 1973 until his death in 1984 and his association with the event adds great prestige to the contest. He wins two Ivor Novello Awards for his contribution to music and receives an honorary degree from the New University of Ulster. He is awarded the Order of the British Empire (OBE) in 1983.

Jimmy Kennedy dies in Cheltenham on April 6, 1984, at the age of 81, and was interred in Taunton, Somerset. In 1997 he is posthumously inducted into the Songwriter’s Hall of Fame.