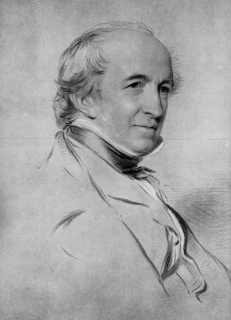

Thomas Spring Rice, 1st Baron Monteagle of Brandon, PC, FRS, FGS, British Whig politician who serves as Chancellor of the Exchequer from 1835 to 1839, dies on February 7, 1866 at Mount Trenchard House, near Foynes, County Limerick.

Spring Rice is born into a notable Anglo-Irish family on February 8, 1790, one of the three children of Stephen Edward Rice, of Mount Trenchard House, and Catherine Spring, daughter and heiress of Thomas Spring of Ballycrispin and Castlemaine, County Kerry, a descendant of the Suffolk Spring family. The family owns large estates in Munster. He is a great grandson of Sir Stephen Rice, Chief Baron of the Irish Exchequer and a leading Jacobite Sir Maurice FitzGerald, 14th Knight of Kerry. His grandfather, Edward, converted the family from Roman Catholicism to the Anglican Church of Ireland, to save his estate from passing in gavelkind.

Spring Rice is educated at Trinity College, Cambridge, and later studies law at Lincoln’s Inn, but is not called to the Bar. His family is politically well-connected, both in Ireland and Great Britain, and he is encouraged to stand for Parliament by his father-in-law, Lord Limerick.

Spring Rice first stands for election in Limerick City in 1818 but is defeated by the Tory incumbent, John Vereker, by 300 votes. He wins the seat in 1820 and enters the House of Commons. He positions himself as a moderate unionist reformer who opposes the radical nationalist politics of Daniel O’Connell and becomes known for his expertise on Irish and economic affairs. In 1824 he leads the committee which establishes the Ordnance Survey in Ireland.

Spring Rice’s fluent debating style in the Commons brings him to the attention of leading Whigs and he comes under the patronage of the Marquess of Lansdowne. As a result, he is made Under-Secretary of State for the Home Department under George Canning and Lord Goderich in 1827, with responsibility for Irish affairs. This requires him to accept deferral of Catholic emancipation, a policy which he strongly supports. He then serves as joint Secretary to the Treasury from 1830 to 1834 under Lord Grey. Following the Reform Act 1832, he is elected to represent Cambridge from 1832 to 1839. In June 1834, Grey appoints him Secretary of State for War and the Colonies, with a seat in the cabinet, a post he retains when Lord Melbourne becomes Prime Minister in July. A strong and vocal unionist throughout his life, he leads the Parliamentary opposition to Daniel O’Connell’s 1834 attempt to repeal the Acts of Union 1800. In a six-hour speech in the House of Commons on April 23, 1834, he suggests that Ireland should be renamed “West Britain.” In the Commons, he also champions causes such as the worldwide abolition of slavery and the introduction of state-supported education.

The Whig government falls in November 1834, after which Spring Rice attempts to be elected Speaker of the House of Commons in early 1835. When the Whigs return to power under Melbourne in April 1835, he is made Chancellor of the Exchequer. As Chancellor, he has to deal with crop failures, a depression and rebellion in North America, all of which create large deficits and put considerable strain on the government. His Church Rate Bill of 1837 is quickly abandoned and his attempt to revise the charter of the Bank of Ireland ends in humiliation. Unhappy as Chancellor, he again tries to be elected as Speaker but fails. He is a dogmatic figure, described by Lord Melbourne as “too much given to details and possessed of no broad views.” Upon his departure from office in 1839, he has become a scapegoat for the government’s many problems. That same year he is raised to the peerage as Baron Monteagle of Brandon, in the County of Kerry, a title intended earlier for his ancestor Sir Stephen Rice. He is also Comptroller General of the Exchequer from 1835 to 1865, despite Lord Howick‘s initial opposition to the maintenance of the office. He differs from the government regarding the exchequer control over the treasury, and the abolition of the old exchequer is already determined upon when he dies.

From 1839 Spring Rice largely retires from public life, although he occasionally speaks in the House of Lords on matters generally relating to government finance and Ireland. He vehemently opposes John Russell, 1st Earl Russell‘s policy regarding the Irish famine, giving a speech in the Lords in which he says the government had “degraded our people, and you, English, now shrink from your responsibilities.”

In addition to his political career, Spring Rice is a commissioner of the state paper office, a trustee of the National Gallery and a member of the senate of the University of London and of the Queen’s University of Ireland. Between 1845 and 1847, he is President of the Royal Statistical Society. In addition, he is a Fellow of the Royal Society and a Fellow of the Geological Society of London. In May 1832 he becomes a member of James Mill‘s Political Economy Club.

Spring Rice is well regarded in Limerick, where he is seen as a compassionate landlord and a good politician. An advocate of traditional Whiggism, he strongly believes in ensuring society is protected from conflict between the upper and lower classes. Although a pious Anglican, his support for Catholic emancipation wins him the favour of many Irishmen, most of whom are Roman Catholic. He leads the campaign for better county government in Ireland at a time when many Irish nationalists are indifferent to the cause. During the Great Famine of the 1840s, he responds to the plight of his tenants with benevolence. The ameliorative measures he implements on his estates almost bankrupts the family and only the dowry from his second marriage saves his financial situation. A monument in honour of him still stands in the People’s Park in Limerick.

Even so, Spring Rice’s reputation in Ireland is not entirely favourable. In a book regarding assisted emigration from Ireland, a process in which a landlord pays for their tenants’ passage to the United States or Australia, Moran suggests that Spring Rice was engaged in the practice. In 1838, he is recorded as having “helped” a boat load of his tenants depart for North America, thereby allowing himself the use of their land. However, he is also recorded as being in support of state-assisted emigration across the British Isles, suggesting that his motivation is not necessarily selfish.

Spring Rice dies at the age of 76 on February 7, 1866. Mount Monteagle in Antarctica and Monteagle County in New South Wales are named in his honour.

(Pictured: Thomas Spring Rice, 1st Baron Monteagle of Brandon (1790-1866), contemporary portrait by George Richmond (1809-1896))