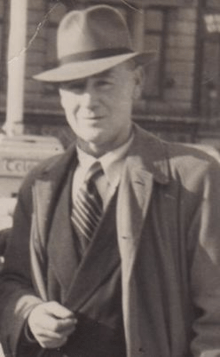

Major General Sir William Bernard Hickie, KCB, Irish-born senior British Army officer and Irish nationalist politician dies in Dublin on November 3, 1950. He sees active service in the Second Boer War from 1899 to 1902, is Assistant Quartermaster General in the Irish Command from 1912 to 1914 and serves in World War I from 1914 to 1918. He commands a brigade of the British Expeditionary Force in 1914 and is commander of the 16th (Irish) Division from 1915 on the Western Front.

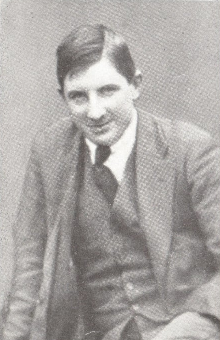

Hickie is born on May 21, 1865, at Slevoir, Terryglass, near Borrisokane, County Tipperary, the eldest of the eight children of Colonel James Francis Hickie and his wife Lucila Larios y Tashara, originally of Castile. He is educated at St. Mary’s College, Oscott, Birmingham, England, a renowned seminary for training youths of prosperous Roman Catholic families.

Hickie attends the Royal Military College, Sandhurst, from 1882 to 1885. He is commissioned into his father’s regiment, the Royal Fusiliers at Gibraltar, in 1885 and serves with them for thirteen years in the Mediterranean, Egypt, and India, during which time he is promoted to captain on November 18, 1892. In 1899 he graduates as captain at the Staff College, Camberley, and is selected when the Second Boer War breaks out as a Special Service Officer in which capacity he acts in various positions of authority and command. He leaves Southampton for South Africa on board the SS Canada in early February 1900 and is promoted from captain of mounted infantry to battalion command as major on March 17, 1900. He is subsequently in command of a corps until eventually at the end of 1900 he is given command of an independent column of all arms. He holds this position for eighteen months. He serves with distinction at the Battle of Bothaville in November 1900 and receives the brevet promotion to lieutenant colonel on November 29, 1900. He serves in South Africa throughout the war, which ends with the Treaty of Vereeniging in June 1902. Four months later he leaves Cape Town on the SS Salamis with other officers and men of the 2nd battalion Royal Fusiliers, arriving at Southampton in late October, when the battalion is posted to Aldershot Garrison. In December 1902 he is elected a Fellow of the Royal Geographical Society (FRGS).

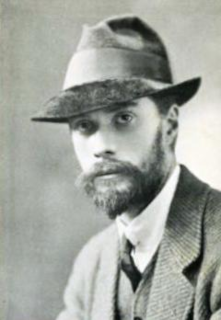

After the end of the war in South Africa there follows various staff appointments, the first from December 1902 as deputy-assistant adjutant general for district staff in the Cork district. In 1907 Hickie is back in regimental service in Dublin and Mullingar with the 1st Royal Fusiliers, where he is in command of the regiment for the last two years. From 1909 to 1912 is appointed to the Staff of the 8th Infantry Division in Cork where for four years he is well known in the hunting field and on the polo ground. In May 1912, he is promoted to colonel and becomes Quartermaster General of the Irish Command at Royal Hospital Kilmainham for which he is appointed a Companion of the Order of the Bath.

When war is declared, the Staff of the Irish Command becomes automatically the staff of the II Army Corps and accordingly with the outbreak of World War I in August 1914, Hickie is promoted to brigadier general and, as part of the British Expeditionary Force in France, takes charge of the Adjutant and Quartermaster-General’s Department during the retreat of the II Corps after the Battle of Mons, to Paris, and during the First Battle of the Marne. In mid-September 1914, he relieves one of the brigadiers in the fighting line as commander of the 13th Brigade (5th Infantry Division) and then commands the 53rd Brigade (18th Infantry Division) until December 1915, when he is ordered home to assume command of the 16th (Irish) Division at Blackburn.

Promoted to major general, Hickie takes over from Lieutenant General Sir Lawrence Parsons. It is politically a highly sensitive appointment which requires the professionalism and political awareness he, fortunately, possesses as the division is formed around a core of Irish National Volunteers in response to Edward Carson‘s Ulster Volunteers. He is much more diplomatic and tactful than his predecessors and speaks of the pride which his new command gives him but does not hesitate to make sweeping changes amongst the senior officers of the Irish Division. After putting the division through intensive training, it leaves under Irish command of which each man takes personal pride. It arrives in December 1915.

In the next two years and four months during which Hickie commands the 16th (Irish) Division, it earns a reputation for aggression and élan and wins many memorials and mentions for bravery in the engagements during the 1916 Battle of Guillemont and the capture of Ginchy, both of which form part of the Battle of the Somme, then during the Battle of Messines, the Third Battle of Ypres and in attacks near Bullecourt in the Battle of Cambrai offensive in November 1917.

During this period the Division makes considerable progress in developing its operational techniques but at a price in losses. The growing shortage of Irish replacement recruits, due to nationalist disenchantment with the war and the absence of conscription in Ireland, is successfully met by Hickie by integrating non-Irish soldiers into the division.

In February 1918, Hickie is invalided home on temporary sick leave, but when in the hospital the German spring offensive begins on March 21, with the result that after his division moves under the command of General Hubert Gough it is practically wiped out and ceases to exist as a division. Although promised a new command, this does not happen before the Armistice in November. He typifies the army’s better divisional commanders, is articulate, intelligent and is competent and resourceful during the BEF’s difficult period 1916–17, laying the foundations for its full tactical success in 1918. He is advanced to Knight Commander of the Order of the Bath in 1918.

Hickie retires from the army in 1922, when the six Irish line infantry regiments that have their traditional recruiting grounds in the counties of the new Irish Free State are all disbanded. He identifies himself strongly with the Home Rule Act and says that its scrapping is a disaster and is equally outspoken in condemning the activities of the Black and Tans. In 1925, he is elected as a member of Seanad Éireann, the Irish Free State Senate.

Hickie holds his seat until the Seanad is dissolved in 1936, to be replaced by Seanad Éireann in 1937. He is President of the Area Council (Southern Ireland) of the Royal British Legion from 1925 to 1948. He never marries.

Hickie dies on November 3, 1950, in Dublin and is buried in Terryglass, County Tipperary.