Hugh Hanna, nicknamed Roaring Hanna, a Presbyterian minister in Belfast known for his anti-Catholicism, dies in Belfast on February 3, 1892.

Hanna is born on February 25, 1821, near Dromara, County Down, the eldest among three sons and two (possibly three) daughters of Peter Hanna, of Dromara farming stock, and his wife Ellen (née Finiston), whose father served in the Black Watch regiment during the Napoleonic Wars. In the 1820s, leaving their children behind, his parents move to Belfast, where his father establishes a business turing out horse–cars. Hanna does not join them until the mid-1830s. His education reflects the modest nature of his upbringing. It is patchy and always combined with paid employment. In the 1830s he attends Bullick’s Academy, a privately run commercial college in Belfast. In the 1840s, seemingly with the intention of preparing for the Presbyterian ministry, he takes classes at Belfast Academical Institution. In 1847, he enters the general assembly’s newly established Theological College and, after some absences, obtains his licence to preach in 1851. During this time he works, first as a woolen draper‘s assistant in High Street and then, after 1844, as a teacher in the national school associated with Townsend Street Presbyterian Church, where he is a member. He resigns his teaching post in January 1852, only a month before being ordained to full-time ministry. On August 25, 1852, he marries Frances (‘Fanny’) Spence Rankin, daughter of James Rankin, a Belfast salesman. Together they have four daughters and two sons.

Hanna’s first, and only, pastorate is in a congregation that emerges out of the evangelistic efforts he and other Townsend Street members had conducted among the working people of north Belfast. In 1852, they begin meeting in the old Berry Street church and quickly grow from 75 to over 750 families. By 1869 a new building is essential and in 1870 the foundation stone for St. Enoch’s church is laid in Carlisle Circus, on property purchased from the Belfast Charitable Society. Opened in 1872 at a cost of nearly £10,000, it seats over 2,000 people and has two galleries. With 800 families and 2,500 Sunday-school scholars, it is one of the largest congregations in Belfast.

Hanna’s influence as the leader of such a large flock is not translated into advancement within the Presbyterian church. Although he serves as the Presbyterian chaplain to the Belfast garrison (1869–91) and as moderator of the presbytery (1879) and synod (1870–71) of Belfast, he does not achieve any position of note within the denomination as a whole. This is most likely because of his penchant for public controversy. Letters to the newspapers, calls for action in presbytery, and public platform debates over issues such as public-house licensing laws, Sabbath observance and property rights, brand him a destablising force. It is no doubt for this reason, rather than for his open-air preaching, of which he does very little, that he acquires his famous sobriquet, “Roaring Hugh.” His aggressive manner in debate is noted by the Belfast News Letter early in his career.

Hanna’s political views contribute to his reputation as an intolerant firebrand. He is part of a small group of Presbyterian clergy, led by the Rev. Henry Cooke, who are staunch defenders of the Protestant interest and active supporters of the conservative cause. He hosts ”anti-popery” lectures in his church and joins the Orange Order, serving briefly, in 1871, as the deputy grand chaplain for Belfast (County Grand Lodge). His determination to uphold the “right” of Protestants to preach in the open air sparks a series of violent sectarian riots and a government inquiry in Belfast in 1857. As the century progresses, and as the Presbyterian community’s political allegiances begin to shift, he becomes one of a group of prominent figures associated with two populist campaigns: opposition in the 1860s to the disestablishment of the Church of Ireland and subsequently to the introduction of home rule. In 1886, as one of the honorary secretaries of the Ulster Constitutional Club, he helps to found the Ulster Loyalist Anti-Repeal Union, a forerunner of what eventually becomes the Ulster Unionist Party.

Such activity overshadows Hanna’s impressive contribution to education. Within St. Enoch’s he establishes an enormous network of Sunday schools and evening classes, including a training institute for teachers. As a former teacher, and later as a commissioner of national education (1880–92), he is a firm advocate of the national system, and sets up six national schools in north and west Belfast.

Hanna receives only two honours: a Doctor of Divinity (DD) from the theological faculty of the Presbyterian Church in Ireland (1885) and a Doctor of Laws (LL.D.) from Galesville University in Galesville, Wisconsin (1888). In good health throughout his life, he dies suddenly of a heart attack on February 3, 1892. Buried with much fanfare in Balmoral Cemetery, Belfast, he is clearly held in high regard by surviving friends and colleagues. In 1892, the Orange Order approves the naming of LOL 1956 as the “Hanna Memorial,” and in 1894 a bronze statue depicting him in full ecclesiastical garb is erected in Carlisle Circus. Since then, his achievements have fallen on hard times. In March 1970, an Irish Republican Army bomb blast topples his statue from its plinth; several high-profile attempts to re-erect it fail. After an arson attack in 1985, and with falling numbers, the decision is taken in 1992 to demolish St. Enoch’s and unite with the neighbouring Duncairn church in a new, much smaller, building on the site.

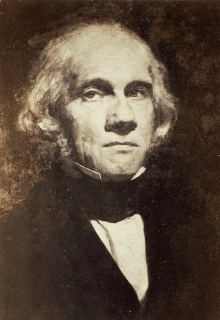

(From: “Hanna, Hugh” by Janice Holmes, Dictionary of Irish Biography, http://www.dib.ie, October 2009 | Pictured: Portrait of Reverend Hugh Hanna by Augustus George Whichelo in 1876, which is part of the collection owned by the National Museums Northern Ireland and is located in the Ulster Museum)