The Teebane bombing takes place on January 17, 1992, at a rural crossroads between Omagh and Cookstown in County Tyrone, Northern Ireland. A roadside bomb destroys a van carrying 14 construction workers who had been repairing a British Army base in Omagh. Eight of the men are killed and the rest are wounded. The Provisional Irish Republican Army (IRA) claims responsibility, saying that the workers were killed because they were “collaborating” with the “forces of occupation.”

Since the beginning of its campaign in 1969, the Provisional IRA has launched frequent attacks on British Army and Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC) bases in Northern Ireland. In August 1985 it begins targeting civilians who offer services to the security forces, particularly those employed by the security forces to maintain and repair its bases. Between August 1985 and January 1992, the IRA kills 23 people who had been working for (or offering services to) the security forces. The IRA also alleges that some of those targeted had links with Ulster loyalist paramilitaries.

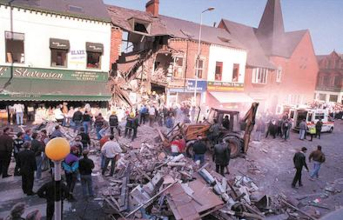

On the evening of January 17, 1992, the 14 construction workers leave work at Lisanelly British Army base in Omagh. They are employees of Karl Construction, based in Antrim. They travel eastward in a Ford Transit van towards Cookstown. When the van reaches the rural Teebane Crossroads, just after 5:00 PM, IRA volunteers detonate a roadside bomb containing an estimated 600 pounds (270 kg) of homemade explosives in two plastic barrels. Later estimates report a 1,500-pound (680 kg) device. The blast is heard from at least ten miles away. It rips through one side of the van, instantly killing the row of passengers seated there. The vehicle’s upper part is torn asunder, and its momentum keeps it tumbling along the road for 30 yards. Some of the bodies of the dead and injured are blown into the adjacent field and ditch. IRA volunteers had detonated the bomb from about 100 yards away using a command wire. A car travelling behind the van is damaged in the explosion, but the driver is not seriously injured. Witnesses report hearing automatic fire immediately prior to the explosion.

Seven of the men are killed outright. They are William Gary Bleeks (25), Cecil James Caldwell (37), Robert Dunseath (25), David Harkness (23), John Richard McConnell (38), Nigel McKee (22) and Robert Irons (61). The van’s driver, Oswald Gilchrist (44), dies of his wounds in hospital four days later. Robert Dunseath is a British soldier serving with the Royal Irish Rangers. The other six workers are badly injured; two of them are members of the Ulster Defence Regiment (UDR). It is the highest death toll from one incident in Northern Ireland since 1988.

The IRA’s East Tyrone Brigade claims responsibility for the bombing soon afterward. It argues that the men were legitimate targets because they were “collaborators engaged in rebuilding Lisanelly barracks” and vowed that attacks on “collaborators” would continue.

Both unionist and Irish nationalist politicians condemn the attack. Sinn Féin president Gerry Adams, however, describes the bombing as “a horrific reminder of the failure of British policy in Ireland.” He adds that it highlights “the urgent need for an inclusive dialogue which can create a genuine peace process.” British Prime Minister John Major visits Northern Ireland within days and promises more troops, pledging that the IRA will not change government policy.

As all of those killed are Protestant, some interpret the bombing as a sectarian attack against their community. Less than three weeks later, the Ulster loyalist Ulster Defence Association (UDA) launches a ‘retaliation’ for the bombing. On February 5, two masked men armed with an automatic rifle and revolver enter Sean Graham’s betting shop on Ormeau Road in an Irish nationalist area of Belfast. The shop is packed with customers at the time. The men fire indiscriminately at the customers, killing five Irish Catholic civilians, before fleeing to a getaway car. The UDA claims responsibility using the cover name “Ulster Freedom Fighters,” ending its statement with “Remember Teebane.” After the shootings, a cousin of one of those killed at Teebane visits the betting shop and says, “I just don’t know what to say but I know one thing – this is the best thing that’s happened for the Provos [Provisional IRA] in this area in years. This is the best recruitment campaign they could wish for.”

The Historical Enquiries Team (HET) conducts an investigation into the bombing and releases its report to the families of the victims. It finds that the IRA unit had initially planned to carry out the attack on the morning of January 17 as the workers made their way to work but, due to fog, it was put off until the afternoon. Although suspects were rounded up and there were arrests in the wake of the attack, nobody has ever been charged or convicted of the bombing.

Karl Construction erects a granite memorial at the site of the attack and a memorial service is held there each year. In January 2012, on the 20th anniversary of the attack, Democratic Unionist Party (DUP) MLA, Trevor Clarke, whose brother-in-law Nigel McKee at age 22 was the youngest person killed in the bombing, demands that republicans provide the names of the IRA bombers.