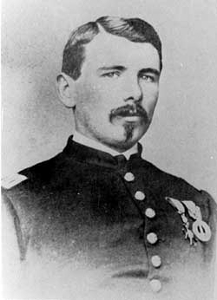

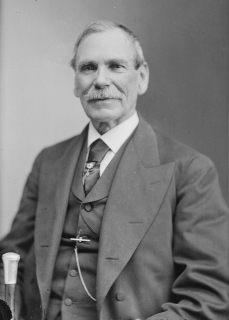

James Shields, Irish American Democratic politician and United States Army officer, is born in Altmore, County Tyrone, in what is now Northern Ireland, on May 10, 1806. He is the only person in U.S. history to serve as a Senator for three different states. He represents Illinois from 1849 to 1855, in the 31st, 32nd, and 33rd Congresses, Minnesota from 1858 to 1859, in the 35th Congress, and Missouri in 1879, in the 45th Congress.

Born and initially educated in Ireland, Shields emigrates to the United States in 1826. He is briefly a sailor and spends time in Quebec before settling in Kaskaskia, Illinois, where he studies and practices law. In 1836, he is elected to the Illinois House of Representatives, and later as State Auditor. His work as auditor is criticized by a young Abraham Lincoln, who with his then fiancée, Mary Todd, publishes a series of inflammatory pseudonymous letters in a local paper. Shields challenges Lincoln to a duel, and the two nearly fight on September 22, 1842, before making peace and eventually becoming friends.

In 1845, Shields is appointed to the Supreme Court of Illinois, from which he resigns to become Commissioner of the U.S. General Land Office. At the outbreak of the Mexican–American War, he leaves the Land Office to take an appointment as brigadier general of volunteers. He serves with distinction and is twice wounded.

In 1848, Shields is appointed to and confirmed by the Senate as the first governor of the Oregon Territory, which he declines. After serving as Senator from Illinois, he moves to Minnesota and there founds the town of Shieldsville. He is then elected as Senator from Minnesota. He serves in the American Civil War and, at the Battle of Kernstown, his troops inflict the only tactical defeat of Stonewall Jackson in the war. He resigns his commission shortly thereafter. After moving multiple times, he settles in Missouri and serves again for three months in the Senate.

Shields dies unexpectedly in Ottumwa, Iowa on June 1, 1879, while on a lecture tour, after reportedly complaining of chest pains. His body is transferred to Carrollton, Missouri by train, where a funeral is held at the Catholic church, and his body escorted to St. Mary’s Cemetery by two companies of the Nineteenth Infantry, the Craig Rifles, and a twenty-piece brass band. His grave remains unmarked for 30 years, until the local government and the U.S. Congress fund a granite and bronze monument there in his honor.

A bronze statue of Shields is given by the State of Illinois to the United States Capitol in 1893 and represents the state in the National Statuary Hall. The statue is sculpted by Leonard Volk and dedicated in December 1893. Statues of Shields also stand in front of the Carroll County Court House in Carrollton, Missouri and on the grounds of the Minnesota State Capitol in Saint Paul.