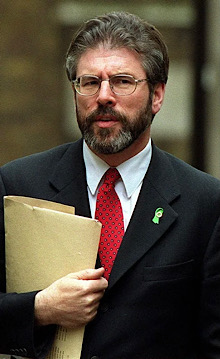

On January 27, 2000, Sinn Féin President Gerry Adams indicates that the Irish Republican Army (IRA) will not deliver arms ahead of the Ulster Unionist Party’s (UUP) February deadline.

With a report due on Monday, January 31, and widely expected to state that the IRA is not ready to disarm, the Northern Ireland peace process appears headed for a fresh crisis. The report by Canadian Gen. John de Chastelain, head of the province’s independent commission overseeing the handing in of weapons, is expected to confirm that no arms have been turned in.

The Ireland on Sunday newspaper says de Chastelain will tell the British and Irish governments that the IRA has put most of its weapons into secret, sealed dumps in the Republic of Ireland. Such disclosures put enormous pressure on Adams, the leader of the Irish republican political party, Sinn Féin.

The UUP, the province’s main Protestant political group, has already threatened to pull out of Northern Ireland‘s fledgling power-sharing government if the IRA does not start disarming.

The UUP calls a top-level party meeting for February 12. A negative report from the decommissioning body will heighten fears that UUP leader David Trimble will make good on his threat to resign as leader of the new government, effectively allowing his party to shut down the province’s first government in 25 years.

Of Adams’s role in the disarmament process, Trimble says, “He asked us to create the circumstances to help him … we did that … we took the risk and created the situation he asked us to create. “Now we hope he now is able to demonstrate his good faith by responding.”

Adams says, “I am concerned at what appears to be an attempt by unionists to hijack the entire process, put up unilateral demands, perhaps in the course of that, tear down the institutions that are only two months in being. I understand why unionists want decommissioning. It is just not within my grasp to deliver it on their terms, and neither is it my responsibility.”

Adams says he can give no assurances that the IRA will hand over its weapons by May 22, the date set by the 1998 Good Friday Agreement for the completion of disarmament, although he stresses he is committed to decommissioning. “No, I can’t and it isn’t up to me,” Adams tells BBC Television when asked if he can guarantee disarmament by May.

Political insiders hint that the report will not be published until Monday (January 31) afternoon, suggesting the highly sensitive document is still being worked on by de Chastelain.

Any unionist pullout from the home-rule government on February 12 will create a political vacuum. Britain may intervene before that to suspend the fledgling executive, in the hope that it can be resurrected quickly if progress eventually is made on disarmament. Sinn Féin warns that either course of action could lead to the IRA breaking off contact with de Chastelain and the ending of disarmament prospects.

Meanwhile, on the eve of the report, thousands of Roman Catholics mark an event and day that symbolizes the province’s past troubles — Bloody Sunday.

Waving Irish flags, some 5,000 protesters retrace the steps of a civil rights march in Londonderry in 1972 that ended in bloodshed when British troops fired on unarmed protesters and killed thirteen people, mostly teenagers. A fourteenth man died later from his wounds. Victims’ relatives and local children carry fourteen white crosses, photos of the dead and a banner that reads, “Bloody Sunday, the day innocence died.” The march passes the scene of the killings and ends in front of Londonderry’s city hall — a spot where the 1972 march was supposed to have finished.

Organizers issue a message to British Prime Minister Tony Blair that they want a forthcoming inquiry not to end in the same way as a probe held within months of the killings, which exonerated the British soldiers by suggesting that some of the victims had handled weapons that day. “Twenty-eight years on from Bloody Sunday, there is still no recognition of the role the British government played in the premeditated attack on unarmed demonstrators,” Barbara de Brun, a top IRA official, tells the crowd.

Relatives of those killed are upset that soldiers who took part in the shootings would be allowed to remain anonymous during the new probe. They are also concerned about a newspaper report that the army recently destroyed thirteen of the rifles used by the soldiers, complicating any ballistics tests at the inquiry.

“Once again, the political and military establishment are up to their old tricks. We won’t accept a public relations exercise,” Alana Burke, who was injured by an armored car during the Bloody Sunday march, tells the crowd.

(From: “Hopes dim for IRA disarmament, peace accord” by Nic Robertson and Reuters, CNN, cnn.com, January 30, 2000)