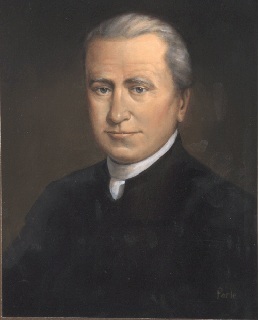

John MacHale, Irish Roman Catholic Archbishop of Tuam and Irish nationalist, dies in Tuam, County Galway on November 7, 1881.

MacHale is born in Tubbernavine, near Lahardane, County Mayo on March 6, 1791, to Patrick and Mary Mulkieran MacHale. He is so feeble at birth that he is baptised at home by Father Andrew Conroy. By the time he is five years of age, he begins attending a hedge school. Three important events happen during his childhood: the Irish Rebellion of 1798, the landing at Killala of French troops, whom the boy, hidden in a stacked sheaf of flax, watches marching through a mountain pass to Castlebar, and a few months later the brutal hanging of Father Conroy on a false charge of high treason.

Being destined for the priesthood, at the age of thirteen, he is sent to a school at Castlebar to learn Latin, Greek, and English grammar. In his sixteenth year the Bishop of Killala gives him a bursarship at St. Patrick’s College, Maynooth. At the age of 24, he is ordained a priest by Daniel Murray, Archbishop of Dublin. In 1825, Pope Leo XII appoints him titular bishop of Maronia, and coadjutor bishop to Dr. Thomas Waldron, Bishop of Killala.

With his friend and ally, Daniel O’Connell, MacHale takes a prominent part in the important question of Catholic emancipation, impeaching in unmeasured terms the severities of the former penal code, which had branded Catholics with the stamp of inferiority. During 1826 his zeal is omnipresent. He calls on the Government to remember how the Act of Union in 1800 was carried by William Pitt the Younger on the distinct assurance and implied promise that Catholic emancipation, which had been denied by the Irish Parliament, should be granted by the Parliament of the Empire.

Oliver Kelly, Archbishop of Tuam, dies in 1834, and the clergy selects MacHale as one of three candidates, to the annoyance of the Government who despatches agents to induce Pope Gregory XVI not to nominate him to the vacant see. Disregarding their request, the pope appoints MacHale Archbishop of Tuam. He is the first prelate since the Reformation who has received his entire education in Ireland. The corrupt practices of general parliamentary elections and the Tithe War cause frequent rioting and bloodshed and are the subjects of denunciation by the new archbishop, until the passing of a Tithes bill in 1838. He also leads the opposition to the Protestant Second Reformation, which is being pursued by evangelical clergy in the Church of Ireland, including the Bishop of Tuam, Killala and Achonry, Thomas Plunket.

The repeal of the Acts of Union 1800, advocated by O’Connell, enlists MacHale’s ardent sympathy and he assists the Liberator in many ways, and remits subscriptions from his priests for this purpose. In his zeal for the cause of the Catholic religion and of Ireland, so long downtrodden, but not in the 1830s, he frequently incurs from his opponents the charge of intemperate language, something not altogether undeserved. In his anxiety to reform abuses and to secure the welfare of Ireland, by an uncompromising and impetuous zeal, he makes many bitter and unrelenting enemies, particularly British ministers and their supporters.

The Great Famine of 1846–47 affects his diocese more than any. In the first year he announces in a sermon that the famine is a divine punishment on his flock for their sins. Then by 1846 he warns the Government as to the state of Ireland, reproaches them for their dilatoriness, and holds up the uselessness of relief works. From England as well as other parts of the world, cargoes of food are sent to the starving Irish. Bread and soup are distributed from the archbishop’s kitchen. Donations sent to him are acknowledged, accounted for, and disbursed by his clergy among the victims.

The death of O’Connell in 1847 is a setback to MacHale as are the subsequent disagreements within the Repeal Association. He strongly advises against the violence of Young Ireland. Over the next 30 years he becomes involved in political matters, particularly those involving the church. Toward the end of his life, he becomes less active in politics.

MacHale attends the First Vatican Council in 1869. He believes that the favourable moment has not arrived for an immediate definition of the dogma of papal infallibility. Better to leave it a matter of faith, not written down, and consequently he speaks and votes in the council against its promulgation. Once the dogma had been defined, he declares the dogma of infallibility “to be true Catholic doctrine, which he believed as he believed the Apostles’ Creed“. In 1877, to the disappointment of the archbishop who desires that his nephew should be his co-adjutor, Dr. John McEvilly, Bishop of Galway, is elected by the clergy of the archdiocese, and is commanded by Pope Leo XIII after some delay, to assume his post. He had opposed this election as far as possible but submits to the papal order.

Every Sunday MacHale preaches a sermon in Irish at the cathedral, and during his diocesan visitations he always addresses the people in their native tongue, which is still largely used in his diocese. On journeys he usually converses in Irish with his attendant chaplain and has to use it to address people of Tuam or the beggars who greet him whenever he goes out. He preaches his last Irish sermon after his Sunday Mass, April 1881. He dies in Tuam seven months later, on November 7, 1881, and is buried in the cathedral at Tuam on November 15.

A marble statue perpetuates his memory on the grounds of the Cathedral of the Assumption of the Blessed Virgin Mary, Tuam. MacHale Park in Castlebar, County Mayo and Archbishop McHale College in Tuam are named after him. In his birthplace the Parish of Addergoole, the local GAA Club, Lahardane MacHales, is named in his honour. The Dunmore GAA team, Dunmore MacHales, is also named after him.