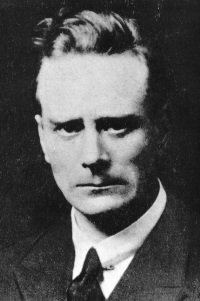

Maria Winifred Carney, also known as Winnie Carney, suffragist, trade unionist and Irish independence activist, is born into a lower-middle class Catholic family in Bangor, County Down on December 4, 1887. Her father is a Protestant who leaves the family. Her mother and six siblings move to Falls Road in Belfast when she is a child.

Carney is educated at St. Patrick’s Christian Brothers School in Donegall Street in Belfast, later teaching at the school. She enrolls at Hughes Commercial Academy around 1910, where she qualifies as a secretary and shorthand typist, one of the first women in Belfast to do so. However, from the start she is looking towards doing more than just secretarial work.

In 1912 Carney is in charge of the women’s section of the Northern Ireland Textile Workers’ Union in Belfast, which she founds with Delia Larkin in 1912. During this period, she meets James Connolly and becomes his personal secretary. She becomes Connolly’s friend and confidant as they work together to improve the conditions for female labourers in Belfast. Carney then joins Cumann na mBan, the women’s auxiliary of the Irish Volunteers, and attends its first meeting in 1914.

Carney is present with Connolly in Dublin‘s General Post Office (GPO) during the Easter Rising in 1916. She is the only woman present during the initial occupation of the building. While not a combatant, she is given the rank of adjutant and is among the final group to leave the GPO. After Connolly is wounded, she refuses to leave his side despite direct orders from Patrick Pearse and Connolly. She leaves the GPO with the rest of the rebels when the building becomes engulfed in flames. They make their new headquarters in nearby Moore Street before Pearse surrenders.

After her capture, Carney is held in Kilmainham Gaol before being moved to Mountjoy Prison and finally to an English prison. By August 1916 she is imprisoned in HM Prison Aylesbury alongside Nell Ryan and Helena Molony. The three request that their internee status be revoked so that they could be held as normal prisoners with Countess Markievicz. Their request is denied, however Carney and Molony are released two days before Christmas 1916.

Carney is a delegate at the 1917 Belfast Cumann na mBan convention. She stands for Parliament as a Sinn Féin candidate for Belfast Victoria in the 1918 United Kingdom general election but loses to the Labour Unionists. Following her defeat, she decides to continue her work at the Irish Transport and General Workers’ Union until 1928. By 1924 she has become a member of the Labour Party. In the 1930s she joins the Socialist Party of Northern Ireland.

Following the Irish Civil War, Carney becomes much more disillusioned with politics. She is very critical and outspoken of Éamon de Valera and his governments.

In 1928 she marries George McBride, a Protestant Orangeman and former member of the Ulster Volunteers. Ironically, the formation of the Ulster Volunteers prompts the formation of the Irish Volunteers, of which Carney was a member. She alienates anyone in her life that does not support her marriage to McBride.

A number of serious health problems limit Carney’s political activities in the late 1930s. She dies in Belfast on November 21, 1943, and is buried in Milltown Cemetery. Her resting place is located years later, and a headstone is erected by the National Graves Association, Belfast. Because she married a Protestant and former Orangeman, she is not allowed to have his name on her gravestone due to the religious differences.

In 2013, the Seventieth Anniversary of Carney’s death is remembered by the Socialist Republican Party. Almost one hundred people attend as a short parade follows, marking and commemorating the work she did for the cause. She is placed in high esteem among the other hundreds of radical women, who stand up for what they believe in, regardless of the consequences they face.