Robert Patterson, naturalist and poet, dies in Belfast on February 14, 1872.

Patterson is born in Belfast on April 18, 1802, the eldest son among three sons and a daughter of Robert Patterson, ironmonger, who supplies equipment for linen mills, and his wife Catherine Patterson (neé Clarke), who is from Dublin. He attends Belfast Royal Academy, and from 1814 is one of the first pupils of the Belfast Academical Institution. He is apprenticed in 1818 to his father, and takes over the business on his father’s death in 1831. Even as a boy, he devotes his leisure time to the study of natural history, and during summer holidays investigates the flora and fauna of the countryside and seaside resorts near Belfast. One of his brothers, William (1805–37), has similar interests.

At the age of 18, Patterson is a founder along with seven others, including James Lawson Drummond, James MacAdam and George Crawford Hyndman, of the Belfast Natural History Society in 1821 (from 1842 “and Philosophical” is added to the society’s name). He is the society’s president for many years, taking a leading role in setting up its museum in 1830–31, and over the years giving many lectures, mostly published in its proceedings. Like many contemporaries, he is an enthusiast for the study of phrenology, and lectures on the subject in Belfast in 1836.

In 1871, Patterson is presented with an illuminated address by the BNHPS for his work to promote the study of natural history, especially as a subject in education. He is the only recipient of the Society’s Templeton medal. Though still engaged in business, he makes a reputation as Belfast’s most distinguished amateur naturalist, publishing monographs such as Letters on the Insects Mentioned by Shakespeare (1838). During dredging excursions in Belfast Lough he discovers several forms of marine life new to Great Britain and Ireland. He is one of the earliest members of the British Association for the Advancement of Science, and secretary of its natural history section from 1839 to 1844. When the Association meets in Belfast in 1852, he acts as local treasurer. He corresponds with prominent naturalists, including Charles Darwin.

In 1843, Patterson publishes in The Zoologist magazine The Reptiles Mentioned by Shakespeare. His Zoology for Schools (2 volumes, 1846, 1848) is followed by First Steps in Zoology (2 volumes, 1849, 1851). A large volume, Zoological Diagrams, with colour illustrations, is published in 1853. All his books have a wide circulation, particularly in the national schools, and stimulates the study of zoology. In accordance with the will of his friend William Thompson, Patterson and James Ramsey Garrett begin to prepare the final volume of Thompson’s Natural History of Ireland for publication. Garrett dies in 1855 and Patterson completes the volume in 1856. He is elected Member of the Royal Irish Academy (MRIA) in 1856, and Fellow of the Royal Society (FRS) in 1859.

Patterson is in the vanguard of a generation of Ulster naturalists who through their work encourage the study of Irish flora and fauna and the establishment of field clubs and natural history societies. He also takes an active part in the public life of Belfast, and in philanthropy. He is a member of the unitarian congregation. He is one of the founders of the Ulster Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals and is particularly interested in the Belfast Society for Promoting Knowledge (the Linen Hall Library), in the Botanic Gardens, and in his old school, Royal Belfast Academical Institution. As a Belfast harbour commissioner (1858–70), he brings commercial and environmental insights to decisions concerning port development.

Patterson marries Mary Elizabeth Ferrar in 1833. She is the daughter of a Belfast magistrate, William H. Ferrar, and writes poetry. Patterson also writes poetry, as well as hymns. Many of their poems are collected in Verses by Robert and Mary Patterson (1886), and they are represented in Selections from the British Poets, published for the use of national schools in 1849. They have five sons and six daughters. His second son, Robert Lloyd Patterson, is also a naturalist. Another son was William H. Patterson. His grandson Robert Patterson, editor of the Irish Naturalist, is secretary of the Belfast Natural History and Philosophical Society, secretary and president of the Belfast Naturalists’ Field Club and secretary of the Ulster Fisheries and Biology Association, which he founds. Robert M. Patterson, a grandson, is a prominent businessman and highly regarded amateur artist. Rosamond Praeger is a granddaughter, and Robert Lloyd Praeger a grandson. The latter writes of his grandfather: “After seventy-five years I can still see him – a man of middle height, and rather formal manner, pursuing his country rambles on Saturday afternoons in black frock-coat and top hat, and pointing out to us delighted children lady-birds and tree-creepers.”

Patterson retires from business in 1865, and dies on February 14, 1872, at his residence in College Square North, Belfast. He is buried in Belfast City Cemetery, where there is a monument to his memory.

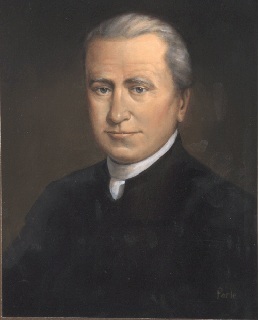

(From: “Patterson, Robert” by Andrew O’Brien, Dictionary of Irish Biography, http://www.dib.ie, October 2009 | Pictured: “Robert Patterson” by Thomas Herbert Maguire, printed by M & N Hanhart lithograph, 1849, National Portrait Gallery)