Thomas “Tom” Michael Kettle, parliamentarian, writer, and soldier, is born on February 9, 1880, in Artane, Dublin, the seventh among twelve children of Andrew Kettle, farmer and agrarian activist, and his wife, Margaret (née McCourt). His father’s record in nationalist politics and land agitation, including imprisonment in 1881, is a valuable political pedigree.

The family is prosperous. Kettle and his brothers attend Christian Brothers’ O’Connell School in Richmond Street, Dublin, before being sent to board at Clongowes Wood College, County Kildare. Popular, fiery, and something of a prankster, he soon proves to be an exceptional scholar and debater, as well as a keen athlete, cyclist, and cricketer. He enrolls in 1897 at University College Dublin (UCD), his contemporaries including Patrick Pearse, Oliver St. John Gogarty and James Joyce. He thrives in student politics, where his rhetorical genius soon wins him many admirers and is recognised in his election as auditor of the college’s Literary and Historical Society. He also co-founds the Cui Bono Club, a discussion group for recent graduates. In 1899, he distributes pro-Boer propaganda and anti-recruitment leaflets, arguing that the British Empire is based on theft, while becoming active in protests against the Irish Literary Theatre‘s staging of The Countess Cathleen by W. B. Yeats. In 1900, however, he is prevented from taking his BA examinations due to a mysterious “nervous condition” – very likely a nervous breakdown. Occasional references in his private diaries and notes suggest that he is prone to bouts of depression throughout his life. He spends the following two years touring in Europe, including a year at the University of Innsbruck, practising his French and German, before taking a BA in mental and moral science of the Royal University of Ireland (RUI) in 1902. He continues to edit the college newspaper, remaining active in student politics. He participates, for example, in protests against the RUI’s ceremonial playing of “God Save the King” at graduations as well as its senate’s apparent support for government policy, threatening on one occasion to burn publicly his degree certificate.

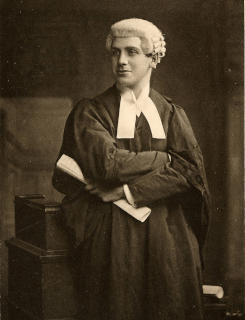

In 1903, Kettle is admitted to the Honourable Society of King’s Inns to read law and is called to the bar two years later. Nonetheless, he soon decides on a career in political journalism. Like his father, he is a keen supporter of the Irish Parliamentary Party (IPP), and in 1904 is a co-founder of the resonantly titled Young Ireland Branch of the United Irish League. Here he comes to the notice of John Redmond, who offers him the prospect of a parliamentary seat, but he chooses instead to put his energies into editing the avowedly pro-Irish-party paper, The Nationist, in which he promises that a home rule administration will uphold women’s rights, industrial self-sufficiency, and Gaelic League control of Irish education. He hopes that the paper will offer a corrective alternative to The Leader, run by D. P. Moran, but in 1905 he is compelled to resign the editorship due to an article thought to be anti-clerical. In July 1906, he is persuaded to stand in a by-election in East Tyrone, which he wins with a margin of only eighteen votes. As one of the youngest and most talented men in an ageing party, he is already tipped as a potential future leader. His oratory is immediately put to good use by the party in a propaganda and fund-raising tour of the United States, as well as on the floor of the House of Commons, where his oratorical skills earn him a fearsome reputation. He firmly advocates higher education for Catholics and the improvement of the Irish economy, while developing a close alliance with Joseph Devlin and the Ancient Order of Hibernians (AOH).

Kettle meanwhile makes good use of his connections to Archbishop William Walsh, the UCD Sodality of the Blessed Virgin Mary, and the Catholic Graduates and Undergraduates Association, as well as political support, to secure the professorship of national economics. T. P. Gill, of the Department of Agriculture and Technical Instruction, exceptionally acts as his referee. His detractors regard the appointment as a political sinecure and Kettle as a somewhat dilettantish “professor of all things,” who frequently neglects his academic duties. However, he takes a keen interest in imperial and continental European economies. He does publish on fiscal policy, even if always taking a pragmatic interest in wider questions, greatly impressing a young Kevin O’Higgins, later Vice-President of the Executive Council of the Irish Free State. He has little time for what he regards as the abstract educational and economic idealism of D. P. Moran. He acknowledges that the “Hungarian policy” of Arthur Griffith has contributed significantly to a necessary debate about the economy, but argues that the Irish are “realists,” that Ireland’s natural resources ought to be scientifically measured, and that the imperial connection is crucial to Ireland’s future development. The achievement of home rule would, he asserts, encourage a healthy self-reliance as opposed to naive belief in self-sufficiency.

Kettle is encouraged by the heightened atmosphere of the constitutional crisis over the 1909 David Lloyd George budget, culminating in the removal of the House of Lords veto, which has been an obstacle to home rule. He is also a supporter of women’s enfranchisement, while stressing that the suffragist cause should not delay or deflect attention from the struggle for home rule. He holds his East Tyrone seat in the January 1910 United Kingdom general election but decides not to stand at the general election in December of the same year. Returning to an essentially journalistic career, he publishes a collection of essays outlining his constitutional nationalist position. He opposes suffragette attacks on private property, but, in contrast, supports the Dublin strikers in 1913, highlighting their harsh working and living conditions. He tries without success to broker an agreement between employers and workers though a peace committee he has formed, on which his colleagues include Joseph Plunkett and Thomas P. Dillon. His efforts are not assisted, however, by an inebriated appearance at a crucial meeting. Indeed, by this time his alcoholic excesses are widely known, forcing him to attend a private hospital in Kent.

In spite of deteriorating health, Kettle becomes deeply involved in the Irish Volunteers formed in November 1913 to oppose the Ulster Volunteers. His appraisal of Ulster unionism is somewhat short-sighted, dismissing it as being “not a party [but] merely an appetite,” and calling for the police to stand aside and allow the nationalists to deal with unionists, whose leaders should be shot, hanged, or imprisoned. These attitudes are mixed in with a developing liberal brand of imperialism based on dominion federalism and devolution, warmly welcoming a pro-home-rule speech by Winston Churchill with a Saint Patrick’s Day toast to “a national day and an empire day.” Nevertheless, he uses his extensive language skills and wide experience of Europe to procure arms for the Irish Volunteers. He is in Belgium when the Germans invade, and the arms he procured are confiscated by the Belgian authorities, to whom they were donated by Redmond on the outbreak of war.

On his return to Dublin, Kettle follows Redmond’s exhortation to support the war effort. He is refused an immediate commission on health grounds, but is eventually granted the rank of lieutenant, with responsibilities for recruitment in Ireland and England. He makes further enemies among the advanced nationalists of Sinn Féin, taunting the party for its posturing and cowardly refusal to confront Ulster unionists, the British Army, and German invaders alike. Coming from a staunchly Parnellite tradition, he is no clericalist, yet he is a devout if liberal Catholic, imbued by his Jesuit schooling with a cosmopolitan admiration for European civilisation which has been reinforced by his European travels, and in particular has been outraged by the German destruction of the ancient university library of Louvain. Despite a youthful flirtation with the philosophy of Friedrich Nietzsche, he comes to regard “Prussianism” as the deadliest enemy of European civilisation and the culture of the Ten Commandments, there not being “room on earth for the two.” He increasingly believes that the German threat is so great that Irish farmers’ sons ought to be conscripted to defend Ireland. He also believes that considerable good might come out of the conflict, exhorting voters in East Galway to support what is practically a future home rule prime minister, cabinet, and Irish army corps. He unsuccessfully seeks nomination as nationalist candidate in the 1914 East Galway by-election in December. Nevertheless, he continues to work tirelessly on behalf of the party, publishing reviews, translations, and treatises widely in such journals as the Freeman’s Journal, The Fortnightly Review, and the Irish Ecclesiastical Record.

As a recruiting officer based far from the fighting, Kettle is stung by accusations of cowardice from advanced nationalists. He had tried repeatedly to secure a front-line position, but was rejected, effectively because of his alcoholism. He is appalled by trench conditions and the prolongation of the war, a disillusionment further encouraged by the Easter Rising, in which his brother-in-law, Francis Sheehy-Skeffington, is murdered by a deranged Anglo-Irish officer, J. C. Bowen-Colthurst. He senses that opinion in Ireland is changing, anticipating that the Easter insurgents will “go down in history as heroes and martyrs,” while he will go down, if at all, as “a bloody British officer.” Nevertheless, he regards the cause of European civilisation as greater than that of Ireland, remaining as determined as ever to secure a combat role. Despite his own poor health and the continuing intensity of the Somme campaign, he insists on returning to his unit, the 9th Battalion, Royal Dublin Fusiliers.

Kettle’s writings demonstrate the mortal danger he is placing himself in, evident not least in his frequently quoted poem, “To my daughter, Betty, the gift of God,” as well as letters settling debts, apologising for old offences, and providing for his family – his wealth at death being less than £200. He has no death wish, wearing body armour frequently, but as Patrick Maume notes, “As with Pearse, there is some self-conscious collusion with the hoped-for cult.” He is killed on September 9, 1916, during the Irish assault on German positions at Ginchy.

Kettle marries Mary Sheehy, alumna of UCD, student activist, suffragist, daughter of nationalist MP David Sheehy, and sister-in-law of his friend Francis Sheehy Skeffington, on September 8, 1909. In 1913 the couple has a daughter, Elizabeth.

Kettle is commemorated by a bust in St. Stephen’s Green, Dublin, and in the House of Commons war memorial in London. He is a man of great passions and proven courage. George William Russell put his sacrifice on a par with Thomas MacDonagh and the Easter insurgents:

“You proved by death as true as they, In mightier conflicts played your part, Equal your sacrifice may weigh, Dear Kettle, of the generous heart (quoted in Summerfield, The myriad minded man, 187).

(From: “Kettle, Thomas Michael (‘Tom’)” by Donal Lowry, Dictionary of Irish Biography, http://www.dib.ie, October 2009 | Pictured: Tom Kettle as a barrister when called to the Irish law bar in 1905)