Gobnait Ní Bhruadair, Irish republican and lifelong radical, dies in Sneem, County Kerry, on January 16, 1955. She campaigns passionately for causes as diverse as the reform of nursing, protection and promotion of the Irish language and the freedom of Ireland from British rule.

Ní Bhruadair is born the Hon. Albinia Lucy Brodrick on December 17, 1861, at 23 Chester Square, Belgrave, London, the fifth daughter of William Brodrick, 8th Viscount Midleton (1830–1907), and his wife, Augusta Mary (née Freemantle), daughter of Thomas Fremantle, 1st Baron Cottesloe. She spends her early childhood in London until the family moves to their country estate in Peper Harow, Surrey in 1870. Educated privately, she travels extensively across the continent and speaks fluent German, Italian and French, and has a reading knowledge of Latin.

Ní Bhruadair’s family is an English Protestant aristocratic one which has been at the forefront of British rule in Ireland since the 17th century. In the early twentieth century it includes leaders of the Unionist campaign against Irish Home Rule. Her brother, St. John Brodrick, 1st Earl of Midleton, is a nominal leader of the Irish Unionist Alliance from 1910 until 1918 when he and other Unionists outside Ulster establish the Irish Unionist Anti-Partition League.

The polar opposite of Ní Bhruadair, her brother is consistent in his low opinion of the Irish and holds imperialist views that warmly embrace much of the jingoism associated with social Darwinism. The young Albinia Lucy Brodrick conforms to her familial political views on Ireland, if her authorship of the pro-Unionist song “Irishmen stand” is an indicator. However, by the start of the twentieth century she becomes a regular visitor to her father’s estate in County Cork. There she begins to educate herself about Ireland and begins to reject the views about Ireland that she had been raised on. In 1902 she writes about the need to develop Irish industry and around the same time she begins to develop an interest in the Gaelic revival. She begins to pay regular visits to the Gaeltacht where she becomes fluent in Irish and is horrified at the abject poverty of the people.

From this point on, Ní Bhruadair’s affinity with Ireland and Irish culture grows intensely. Upon her father’s death in 1907 she becomes financially independent and in 1908 purchases a home near West Cove, Caherdaniel, County Kerry. The same year she establishes an agricultural cooperative there to develop local industry. She organises classes educating people on diet, encourages vegetarianism and, during the smallpox epidemic of 1910, nurses the local people. Determined to establish a hospital for local poor people, she travels to the United States to raise funds.

There Ní Bhruadair takes the opportunity to study American nursing, meets leading Irish Americans and becomes more politicised to Ireland’s cause. Upon her return to Kerry, she establishes a hospital in Caherdaniel later in 1910. She renames the area Ballincoona (Baile an Chúnaimh, ‘the home of help’), but it is unsuccessful and eventually closes for lack of money. She writes on health matters for The Englishwoman and Fortnightly, among other journals, is a member of the council of the National Council of Trained Nurses and gives evidence to the royal commission on venereal disease in 1914.

Ní Bhruadair is a staunch supporter of the 1916 Easter Rising. She joins both Cumann na mBan and Sinn Féin. She visits some of the 1,800 Irish republican internees held by the British in Frongoch internment camp in Wales and writes to the newspapers with practical advice for intending visitors. She canvasses for various Sinn Féin candidates during the 1918 Irish general election and is a Sinn Féin member on Kerry County Council (1919–21), becoming one of its reserve chairpersons. During the Irish War of Independence, she shelters Irish Republican Army (IRA) volunteers and consequently her home becomes the target for Black and Tans attacks.

Along with Dr. Kathleen Lynn she works with the Irish White Cross to distribute food to the dependents of IRA volunteers. By the end of the Irish War of Independence she has become hardened by the suffering she has seen and is by now implacably opposed to British rule in Ireland. She becomes one of the most vociferous voices against the Anglo-Irish Treaty of December 6, 1921. She becomes a firebrand speaker at meetings in the staunchly republican West Kerry area. In April 1923 she is shot by Irish Free State troops and arrested. She is subsequently imprisoned in the North Dublin Union, where she follows the example of other republicans and goes on hunger strike. She is released two weeks later. Following the formation of Fianna Fáil by Éamon de Valera in 1926, she continues to support the more hardline Sinn Féin.

In October 1926 Ní Bhruadair represents Munster at the party’s Ardfheis. She owns the party’s semi-official organ, Irish Freedom, from 1926–37, where she frequently contributes articles and in its later years acts as editor. Her home becomes the target of the Free State government forces in 1929 following an upsurge in violence from anti-Treaty republicans against the government. She and her close friend Mary MacSwiney leave Cumann na mBan following the decision by its members at their 1933 convention to pursue social radicalism. The two then establish an all-women’s nationalist movement named Mná na Poblachta, which fails to attract many new members.

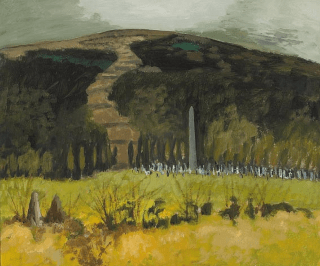

Ní Bhruadair continues to speak Irish and regularly attends Conradh na Gaeilge branch meetings in Tralee. Although sympathetic to Catholicism, she remains a member of the Anglican Church of Ireland, and regularly plays the harmonium at Sneem’s Church of Ireland services. Described by a biographer as “a woman of frugal habits and decided opinions, she was in many ways difficult and eccentric.” She dies on January 16, 1955, and is buried in the Church of Ireland graveyard in Sneem, County Kerry.

In her will Ní Bhruadair leaves most of her wealth (£17,000) to republicans “as they were in the years 1919 to 1921.” The vagueness of her bequest leads to legal wrangles for decades. Finally, in February 1979, Justice Seán Gannon rules that the bequest is void for remoteness, as it is impossible to determine which republican faction meets her criteria.