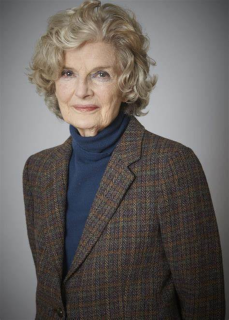

Annie Elizabeth Fredericka Horniman CH, English theatre patron and manager, is born at Surrey Mount, Forest Hill, London, on October 3, 1860. She establishes the Abbey Theatre in Dublin and founds the first regional repertory theatre company in Britain at the Gaiety Theatre in Manchester. She encourages the work of new writers and playwrights, including W. B. Yeats, George Bernard Shaw and members of what become known as the Manchester School of dramatists.

Horniman, the elder child of Frederick John Horniman and his first wife Rebekah (née Emslie). Her father is a tea merchant and the founder of the Horniman Museum. Her grandfather is John Horniman who founds the family tea business of Horniman and Company. She and her younger brother, Emslie, are educated privately at their home. Her father is opposed to the theatre, which he considers sinful, but their German governess takes her and Emslie secretly to a performance of The Merchant of Venice at The Crystal Palace when she is fourteen years old.

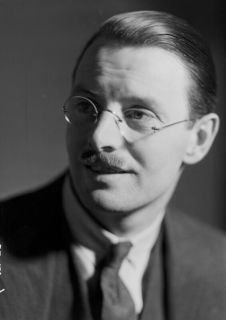

Horniman’s father allows her to enter the Slade School of Fine Art in 1882. Here she discovers that her talent in art is limited but she develops other interests, particularly in the theatre and opera. She takes great pleasure in Richard Wagner‘s Der Ring des Nibelungen and in Henrik Ibsen‘s plays. She cycles in London and twice over the Alps, smokes in public and explores alternative religions. The “lonely rich girl” has become “an independent-minded woman.” In 1890 she joins the occult society, the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn, where she remains a member until disagreements with its leaders lead to her resignation in 1903. During this time she meets and becomes a friend of W. B. Yeats, acting as his amanuensis for some years. Their friendship endures. Frank O’Connor recalls that on the day Yeats hears of her death, he spends the entire evening speaking of his memories of her.

Horniman’s first venture into the theatre is in 1894 and is made possible by a legacy from her grandfather. She anonymously supports her friend Florence Farr in a season of new plays at the Royal Avenue Theatre, London. This includes a new play by Yeats, The Land of Heart’s Desire, and the première of George Bernard Shaw’s play Arms and the Man. In 1903, Yeats persuades her to go to Dublin to back productions by the Irish National Theatre Society. Here she discovers her skill as a theatre administrator. She purchases a property and develops it into the Abbey Theatre, which opens in December 1904. Although she moves back to live in England, she continues to support the theatre financially until 1910. Meanwhile, in Manchester she purchases and renovates the Gaiety Theatre in 1908 and develops it into the first regional repertory theatre in Britain.

At the Gaiety, Horniman appoints Ben Iden Payne as the director and employs actors on 40-week contracts, alternating their work between large and small parts. The plays produced include classics such as Euripides and Shakespeare, and she introduces works by contemporary playwrights such as Ibsen and Shaw. She also encourages local writers who form what becomes known as the Manchester School of dramatists, the leading members of which are Harold Brighouse, Stanley Houghton and Allan Monkhouse. The Gaiety company undertakes tours of the United States and Canada in 1912 and 1913. Horniman becomes a well-known public figure in Manchester, lecturing on subjects which include women’s suffrage and her views about the theatre. In 1910 she is awarded the honorary degree of MA by the University of Manchester. During World War I the Gaiety continues to stage plays but financial difficulties lead to the disbandment of the permanent company in 1917, following which productions in the theatre are by visiting companies. In 1921 she sells the theatre to a cinema company.

As a result of her tea connection, Horniman is known as “Hornibags.” She holds court at the Midland Hotel, wearing exotic clothing and openly smoking cigarettes, which is considered scandalous at the time. She introduces Manchester to what is called at the time “the play of ideas.” The theatre critic James Agate notes that her high-minded theatrical ventures have “an air of gloomy strenuousness” about them.

Horniman moves to London where she keeps a flat in Portman Square. In 1933 she is made a Companion of Honour. She and Algernon Blackwood might be the only past or present members of an occult society to receive a United Kingdom honour.

Horniman dies, unmarried, on August 6, 1937, while visiting friends in Shere, Surrey. Her estate amounts to a little over £50,000. The Annie Horniman Papers are held in the John Rylands Research Institute and Library at the University of Manchester. Her portrait, painted by John Butler Yeats in 1904, hangs in the public area of the Abbey Theatre.