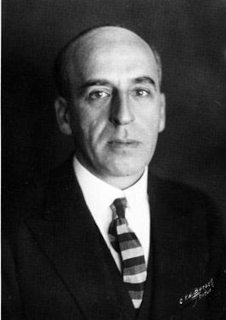

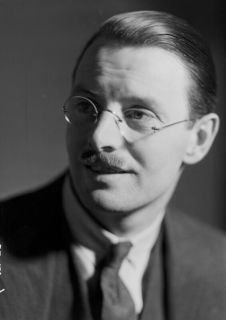

Uinseann Ó Rathaille MacEoin, Irish architect, journalist, republican campaigner and historian, is born in Pomeroy, County Tyrone, on July 4, 1920.

MacEoin is born Vincent O’Rahilly McGuone to Malachy McGuone, owner of the Central Hotel in Pomeroy and a wine and spirit merchant, and Catherine (née Fox). He has three siblings. Both of his parents are nationalists, and name all their children after leaders of the Easter Rising in 1916. Under the First Dáil in 1918, his father is appointed a judge. This results in him being interned on the prison ship Argenta on Larne Lough from 1922 to 1923. The family moves to Dublin after his release. His father dies in 1933, which leads to his wife running a workingmen’s café in East Essex Street. The family later lives on Marlborough Road, Donnybrook.

MacEoin attends boarding school at Blackrock College and is then articled to the architectural practice of Vincent Kelly in Merrion Square. As an active republican, he lives in a house on Northumberland Road from late 1939 to May 1940 where he helps in the production and distribution of an Irish Republican Army (IRA) weekly newspaper, War News. The IRA is banned by the Irish government in 1936, and its bombing campaign in Britain in 1939 is viewed by the government as a threat to Irish neutrality. MacEoin is among a group of republicans arrested in June 1940 and imprisoned in Arbour Hill Prison for a year. Once released, he is rearrested and interned at the Curragh for three years. He is sentenced to 3-months imprisonment in October 1943 for possession of incriminating documents. He is also charged with possession of ammunition, but testifies he was given the rounds against his will and never appears to have engaged in any violence. During his internment, he is taught the Irish language by Máirtín Ó Cadhain and is exposed to the socialist views of his fellow inmates. It is at this time that he adopts the Irish form of his name, Uinseann MacEoin.

While imprisoned in the 1940s, MacEoin continues his studies by correspondence and qualifies as an architect in 1945 at University College Dublin (UCD). His designs for a memorial garden in 1946 to those who died during the Irish War of Independence are commended. In 1959, he designs the site in Ballyseedy, County Kerry, for a monument by Yann Goulet commemorating those killed in the Irish Civil War and members of the IRA from Kerry who died. In 1948, he qualifies in town planning and takes up a position with Michael Scott‘s architectural practice. He works for a short time with Dublin Corporation, with their housing department, before establishing his own practice in 1955.

During the 1950s, MacEoin is a contributing editor on interior design in Hugh McLaughlin‘s magazine Creation, becoming editor of Irish Architect and Contractor in 1955. He enters into a partnership with Aidan Kelly in 1969 as MacEoin Kelly and Associates. In the early 1970s, he designs a shopping and housing development outside Dundalk, called Ard Easmuinn. Throughout the 1960s and 1970s, he continues as an influential architectural journalist, founding and editing Build from 1965 to 1969, and later Plan. His company, Pomeroy Press, publishes Plan along with other serials such as Stream and Field. He writes a large proportion of the copy in these periodicals, much under his own name, but he also uses pseudonyms, in particular in Plan as “Michael O’Brien.” He writes about his strong views on social housing, national infrastructure, and foreign and slum landlords, often libelously.

Despite his republican and socialist views, MacEoin is a staunch advocate for the preservation of Georgian Dublin, and campaigns for their preservation. On this topic, he writes letters to newspapers, takes part in television and radio discussions, writes comment pieces and editorials, speaks at public hearings, and takes part in direct protests such as sit-ins in buildings including those on Baggot Street, Pembroke Street, Hume Street, and Molesworth Street. He is also an active member of the Irish Georgian Society, and he campaigns actively against the road widening schemes in Dublin the 1970s and 1980s.

MacEoin and his wife purchase five Georgian houses on Mountjoy Square and three on Henrietta Street in the 1960s, all almost derelict. They refurbish them and lease them out, under the company name Luke Gardiner Ltd. He renames the 5 Henrietta Street property James Bryson House. His architectural practice moves into one of the Mountjoy Square houses. Along with fellow campaigners, Mariga Guinness and Deirdre Kelly, this demonstrates that these buildings can be salvaged and are not the dangerous structures other architects and developers claim them to be. He also purchases and saves Heath House, near Portlaoise, County Laois, living there toward the end of his life. He offers free conservation and architectural advice to community groups and is a volunteer on the renovation works on projects including Tailors’ Hall.

MacEoin remains politically active, joining Clann na Poblachta, the Wolfe Tone Societies (WTS), the Dublin Civic Group, the Northern Ireland Civil Rights Association (NICRA) and the Irish Anti-Apartheid Movement. To what extent he is involved in republican or IRA activities after 1945 is not clear. However, in March 1963, he is called a witness to a case in Scotland involving a Glasgow bookmaker by the name of Samuel Docherty and the Royal Bank of Scotland. Docherty claims the bank owes him £50,000. MacEoin testifies that in February 1962 he had travelled with £50,000 in cash from Dublin to lodge to Docherty’s account in the Royal Bank of Scotland in Belfast, as a loan. When asked about the origin of this large sum of money, he states it was supplied by another person but does not divulge that person’s name. This immediately triggers the court’s suspicions, and the judge warns MacEoin he will be contempt of court if he does not name the supplier of the money. He is placed in police custody for the day, and eventually he agrees to give the name in writing in confidence to the judge. The judge ultimately rules that Docherty is guilty of attempted fraud and perjury and that MacEoin’s involvement reeks of criminality. However, no further action is ever brought forward against Docherty or MacEoin.

In Sinn Féin‘s 1971 Éire Nua social and economic programme, MacEoin writes the chapter on “Planning,” and attends meetings in Monaghan in the early 1970s on the Dáil Uladh, a parliament for the 9-county Ulster province. In 1981, during the republican hunger strikes, one of his Mountyjoy Square houses is used as the national headquarters of the National H-Block Committee. Following the 1986 Sinn Féin split, he supports Republican Sinn Féin. He is a founding member of the Constitutional Rights Campaign in 1987, a group which aims to protect the rights of Irish citizens in the European Economic Community (EEC), having campaigned against Ireland joining the EEC in the early 1970s. In 1978, he is sentenced to two weeks in Mountjoy Prison for non-payment of a fine issued for not having a television licence. He had refused to buy one to protest the lack of Irish language programming.

As an environmentalist, MacEoin opposes private car ownership, and advocates for cycleways and the redevelopment of the railway lines. He writes about the “greenhouse effect” as early as 1969. As a hill walker and mountaineer, he claims to be the first Irishman to register successful climbs of all 284 Scottish peaks, known as the Munros, in 1987. He also climbs in the Alps and the Pyrenees.

MacEoin writes three books on his memories, and those of his former comrades: Survivors (1980), on the lives of leading Irish republicans, Harry (1986), a part biography part autobiography of Harry White, and The IRA in the twilight years 1923–48 (1997). He also publishes a novel, Sybil: a tale of innocence (1992) with his publishing house, Argenta, under the name Eoin O’Rahilly. He also interviews and records dozens of Republicans as part of his research for his books. These recordings are later converted into a digital oral history archive held in trust by the Irish Defence Forces.

MacEoin marries Margaret Russell in 1956 in Navan, County Meath. They have a daughter and two sons.

MacEoin dies in a nursing home in Shankill, Dublin, on December 21, 2007. His estate at the time of his death is valued at over €3 million. His son, Nuada, takes over his father’s architectural practice.