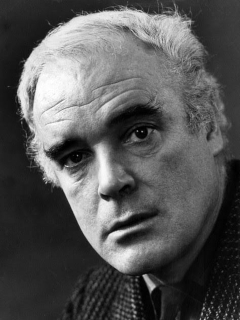

Patrick George McGee, Northern Irish actor and director of stage and screen known professionally as Patrick Magee, is born on March 31, 1922, in Armagh, County Armagh, Northern Ireland. He is known for his collaborations with Samuel Beckett and Harold Pinter, as well as creating the role of the Marquis de Sade in the original stage and screen productions of Marat/Sade. He also appears in numerous horror films and in two Stanley Kubrick films, A Clockwork Orange and Barry Lyndon.

McGee is born into a middle-class family at 2 Edward Street in Armagh. The eldest of five children, he is educated at St. Patrick’s Grammar School, Armagh. He changes the spelling of his surname to Magee when he begins performing, most likely to avoid confusion with another actor.

Magee’s first stage experience in Ireland is with Anew McMaster’s touring company, performing the works of William Shakespeare. It is here that he first works with Pinter. He is then brought to London by Tyrone Guthrie for a series of Irish plays. He meets Beckett in 1957 and soon records passages from the novel Molloy and the short story From an Abandoned Work for BBC Radio. Impressed by “the cracked quality of Magee’s distinctly Irish voice,” Beckett requests copies of the tapes and writes Krapp’s Last Tape especially for the actor. First produced at the Royal Court Theatre in London on October 28, 1958, the play stars Magee and is directed by Donald McWhinnie. A televised version is later broadcast by BBC Two on November 29, 1972.

In 1964, Magee joins the Royal Shakespeare Company, after Pinter, directing his own play, The Birthday Party, specifically requests him for the role of McCann. In 1965 he appears in Peter Weiss‘s Marat/Sade, and when the play transfers to Broadway he wins a Tony Award. He also appears in the 1966 RSC production of Staircase opposite Paul Scofield.

Magee’s early film roles include Joseph Losey‘s The Criminal (1960) and The Servant (1963), the latter an adaptation scripted by Pinter. He also appears as Surgeon-Major James Henry Reynolds in Zulu (1964), Séance on a Wet Afternoon (1964), Anzio (1968), and in the film versions of Marat/Sade (1967) and The Birthday Party (1968). He is perhaps best known for his role as the victimised writer Frank Alexander, who tortures Alex DeLarge with Ludwig van Beethoven‘s music, in Stanley Kubrick’s film A Clockwork Orange (1971). His other role for Kubrick is as Redmond Barry’s mentor, the Chevalier de Balibari, in Barry Lyndon (1975).

McGee also appears in Young Winston (1972), The Final Programme (1973), Galileo (1975), Sir Henry at Rawlinson End (1980), The Monster Club and Chariots of Fire (1981) but is most often seen in horror films. These include Roger Corman‘s The Masque of Red Death (1964), and the Boris Karloff vehicle Die, Monster, Die! (1965) for AIP; The Skull (1965), Tales from the Crypt (1972), Asylum (1972), and And Now the Screaming Starts! (1973) for Amicus Productions; Demons of the Mind (1972) for Hammer Film Productions; and Walerian Borowczyk‘s Docteur Jekyll et les femmes (1981).

Patrick McGee dies of a heart attack at his flat in Fulham, London on August 14, 1982, at the age of 60, according to obituaries in The Herald and The New York Times. On July 29, 2017, a blue plaque is unveiled in Edward Street, Armagh to mark Patrick McGee’s birthplace.