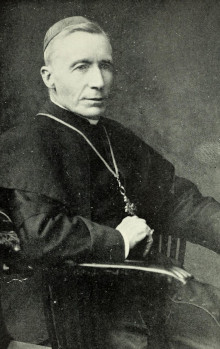

Michael Logue, Irish prelate of the Roman Catholic Church, dies in Armagh, County Armagh, Northern Ireland on November 19, 1924. He serves as Archbishop of Armagh and Primate of All Ireland from 1887 until his death. He is created a cardinal in 1893.

Logue is born in Kilmacrennan, County Donegal in the west of Ulster on October 1, 1840. He is the son of Michael Logue, a blacksmith, and Catherine Durning. From 1857 to 1866, he studies at Maynooth College, where his intelligence earns him the nickname the “Northern Star.” Before his ordination to the priesthood, he is assigned by the Irish bishops as the chair of both theology and belles-lettres at the Irish College in Paris in 1866. He is ordained priest in December of that year.

Logue remains on the faculty of the Irish College until 1874, when he returns to Donegal as administrator of a parish in Letterkenny. In 1876, he joins the staff of Maynooth College as professor of Dogmatic Theology and Irish language, as well as the post of dean.

On May 13, 1879, Logue is appointed Bishop of Raphoe by Pope Leo XIII. He receives his episcopal consecration on the following July 20 from Archbishop Daniel McGettigan, with Bishops James Donnelly and Francis Kelly serving as co-consecrators, at the pro-cathedral of Raphoe. He is involved in fundraising to help people during the 1879 Irish famine, which, due to major donations of food and government intervention never develops into a major famine. He takes advantage of the Intermediate Act of 1878 to enlarge the Catholic high school in Letterkenny. He is also heavily involved in the Irish temperance movement to discourage the consumption of alcohol.

On April 18, 1887, Logue is appointed Coadjutor Archbishop of the Archdiocese of Armagh and Titular Archbishop of Anazarbus. Upon the death of Archbishop MacGettigan, he succeeds him as Archbishop of Armagh, and thus Primate of All Ireland, on December 3 of that year. He is created Cardinal-Priest of Santa Maria della Pace by Pope Leo XIII in the papal consistory of January 19, 1893.

Logue thus becomes the first archbishop of Armagh to be elevated to the College of Cardinals. He participates in the 1903, 1914, and 1922 conclaves that elect popes Pius X, Benedict XV, and Pius XI respectively. He takes over the completion of the Victorian gothic St. Patrick’s Cathedral in Armagh. The new cathedral, which towers over Armagh, is dedicated on July 24, 1904.

Logue publicly supports the principle of Irish Home Rule throughout his long reign in both Raphoe and Armagh, though he is often wary of the motives of individual politicians articulating that political position. He maintains a loyal attitude to the British Crown during World War I, and on June 19, 1917, when numbers of the younger clergy are beginning to take part in the Sinn Féin agitation, he issues an “instruction” calling attention to the teaching of the Roman Catholic Church as to the obedience due to legitimate authority, warning the clergy against belonging to “dangerous associations,” and reminding priests that it is strictly forbidden by the statutes of the National Synod to speak of political or kindred affairs in the church.

In 1918, however, Logue places himself at the head of the opposition to the extension of the Military Service Act of 1916 to Ireland, in the midst of the Conscription Crisis of 1918. Bishops assess that priests are permitted to denounce conscription on the grounds that the question is not political but moral. He also involves himself in politics for the 1918 Irish general election, when he arranges an electoral pact between the Irish Parliamentary Party and Sinn Féin in three constituencies in Ulster and chooses a Sinn Féin candidate in South Fermanagh – the imprisoned Republican, Seán O’Mahony.

Logue opposes the campaign of murder against the police and military begun in 1919, and in his Lenten pastoral of 1921 he vigorously denounces murder by whomsoever committed. This is accompanied by an almost equally vigorous attack on the methods and policy of the government. He endorses the Anglo-Irish Treaty in 1921.

In 1921, the death of Cardinal James Gibbons makes Logue archpriest (protoprete) of the College of Cardinals. He is more politically conservative than Archbishop of Dublin William Joseph Walsh, which creates tension between Armagh and Dublin. In earlier life he was a keen student of nature and an excellent yachtsman.

Cardinal Michael Logue dies in Ara Coeli, the residence of the archbishop, on November 19, 1924, and is buried in a cemetery in the grounds of St. Patrick’s Cathedral, Armagh.