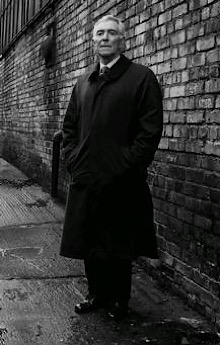

James Nesbitt MBE, a Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC) Detective Chief Inspector who is best known for heading the Murder Squad team investigating the notorious Shankill Butchers‘ killings in the mid-1970s, dies on August 27, 2014, following a brief illness.

Nesbitt is born on September 29, 1934, in Belfast, Northern Ireland, the son of James, an electrician, and Ellen. He is brought up in the Church of Ireland religion and lives with his parents and elder sister, Maureen, in a terraced house in Cavehill Road, North Belfast, which is considered to be a middle class area at the time. Having first attended the Model Primary School in Ballysillan Road, in 1946 he moves on to Belfast Technical High School where he excels as a pupil. From an early age, he is fascinated by detective stories and dreams about becoming a detective himself.

As a child, Nesbitt avidly reads about all the celebrated murder trials in the newspapers. At the age of 16, he opts to leave school and goes to work as a sales representative for a linen company where he remains for seven years.

At the age of 23, Nesbitt seeks a more exciting career and realises his childhood dream by joining the Royal Ulster Constabulary as a uniformed constable. He applies at the York Road station in Belfast and passes his entry exams. His first duty station is at Swatragh, County Londonderry. During this period, the Irish Republican Army‘s Border Campaign is being waged. He earns two commendations during the twelve months he spends at the Swatragh station, having fought off two separate IRA gun attacks which had seen an Ulster Special Constabulary man shot. In 1958, he is transferred to the Coleraine RUC station where his superiors grant him the opportunity to assist in detective work. Three years later he is promoted to the rank of detective.

Nesbitt marries Marion Wilson in 1967 and begins to raise a family. By 1971 he is back in his native Belfast and holds the rank of Detective Sergeant. He enters the RUC’s Criminal Investigation Department (CID) section and is based at Musgrave Street station. Many members of the RUC find themselves targeted by both republican and loyalist paramilitaries as the conflict known as The Troubles grows in intensity during the late 1960s and early 1970s.

In September 1973, Nesbitt is promoted to Detective Inspector and moves to head up the RUC’s C or “Charlie” Division based in Tennent Street, off the Shankill Road, the heartland of loyalism and home of many loyalist paramilitaries. C Division covers not only the Shankill but also the republican Ardoyne and “The Bone” areas. Although he encounters considerable suspicion from his subordinates when he arrives at Tennent Street, he manages to eventually create much camaraderie within the ranks of those under his command when before there had been rivalry and discord. C Division loses a total of twelve men as a result of IRA attacks. During his tenure as Detective Chief Inspector at Tennent Street, he and his team investigate a total of 311 killings and solve around 250 of the cases.

By 1975, Nesbitt is encountering death and serious injury on a daily basis as the violence in Northern Ireland shows no signs of abating. However, toward the end of the year, he is faced with the first of a series of brutal killings that add a new dimension to the relentless tit-for-tat killings between Catholics and Protestants that has already made 1975 “one of the bloodiest years of the conflict.”

The Shankill Butchers are an Ulster loyalist paramilitary gang, many of whom are members of the Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF), that is active between 1975 and 1982 in Belfast. It is based in the Shankill area and is responsible for the deaths of at least 23 people, most of whom are killed in sectarian attacks.

The gang kidnaps, tortures and murders random civilians suspected of being Catholics. Each is beaten ferociously and has their throat slashed with a butcher knife. Some are also tortured and attacked with a hatchet. The gang also kills six Ulster Protestants over personal disputes and two other Protestants mistaken for Catholics.

Most of the gang are eventually caught by Nesbitt and his Murder Squad and, in February 1979, receive the longest combined prison sentences in United Kingdom legal history.

In 1991, after Channel 4 broadcasts a documentary claiming that the Ulster Loyalist Central Co-ordinating Committee had been reorganised as an alliance between loyalist paramilitaries, senior RUC members and leader figures in Northern Irish business and finance, Nesbitt and Detective Inspector Chris Webster are appointed by Chief Constable Hugh Annesley to head up an internal inquiry into the collusion allegations. The investigation delivers its verdict in February 1993 and exonerates all those named as Committee members who did not have previous terrorist convictions arguing that they are “respectable members of the community” and in some cases “the aristocracy of the country.”

Prior to his retirement, Nesbitt has received a total of 67 commendations, which is the highest number ever given to a policeman in the history of the United Kingdom. In 1980, he is awarded the MBE “in recognition of his courage and success in combating terrorism.”

Nesbitt dies on August 27, 2014, after a brief illness.