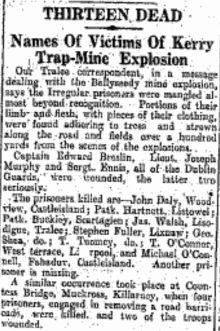

The Milltown Cemetery attack takes place on March 16, 1988, at Milltown Cemetery in Belfast, Northern Ireland. During the large funeral of three Provisional Irish Republican Army members killed in Gibraltar, an Ulster Defence Association (UDA) member, Michael Stone, attacks the mourners with hand grenades and pistols.

On March 6, 1988, Provisional IRA members Daniel McCann, Seán Savage and Mairéad Farrell are shot dead by the Special Air Service (SAS) in Gibraltar, in Operation Flavius. The three had allegedly been preparing a bomb attack on British military personnel there, but the deaths outrage republicans as the three were unarmed and shot without warning. Their bodies arrive in Belfast on March 14 and are taken to their family homes. Tensions are high as the security forces flood the neighbourhoods where they had lived, to try to prevent public displays honouring the dead. For years, republicans have complained about heavy-handed policing of IRA funerals, which have led to violence. In a change from normal procedure, the security forces agree to stay away from the funeral in exchange for guarantees that there will be no three-volley salute by IRA gunmen. The British Army and Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC) will instead keep watch from the sidelines. This decision is not made public.

Michael Stone is a loyalist, a member of the Ulster Defence Association (UDA) who had been involved in several killings and other attacks, and who describes himself as a “freelance loyalist paramilitary.” He learns that there will be little security force presence at the funerals, and plans “to take out the Sinn Féin and IRA leadership at the graveside.” He says his attack is retaliation for the Remembrance Day bombing four months earlier, when eleven Protestants had been killed by an IRA bomb at a Remembrance Sunday ceremony. He claims that he and other UDA members considered planting bombs in the graveyard but abandon the plan because the bombs might miss the republican leaders.

The funeral service and Requiem Mass go ahead as planned, and the cortege makes its way to Milltown Cemetery, off the Falls Road. Present are thousands of mourners and top members of the IRA and Sinn Féin, including Sinn Féin leader Gerry Adams and Martin McGuinness. Two RUC helicopters hover overhead. Stone claims that he entered the graveyard through the front gate with the mourners and mingled with the large crowd, although one witness claims to have seen him enter from the M1 motorway with three other people.

As the third coffin is about to be lowered into the ground, Stone throws two grenades, which have a seven-second delay, toward the republican plot and begins shooting. The first grenade explodes near the crowd and about 20 yards from the grave. There is panic and confusion, and people dive for cover behind gravestones. Stone begins jogging toward the motorway, several hundred yards away, chased by dozens of men and youths. He periodically stops to shoot and throw grenades at his pursuers.

Three people are killed while pursuing Stone – Catholic civilians Thomas McErlean (20) and John Murray (26), and IRA member Caoimhín Mac Brádaigh (30), also known as Kevin Brady. During the attack, about 60 people are wounded by bullets, grenade shrapnel and fragments of marble and stone from gravestones. Among those wounded is a pregnant mother of four, a 72-year-old grandmother and a ten-year-old boy. Some fellow loyalists say that Stone made the mistake of throwing his grenades too soon. The death toll would likely have been much higher had the grenades exploded in mid-air, “raining lethal shrapnel over a wide area.”

A white van that had been parked on the hard shoulder of the motorway suddenly drives off as Stone flees from the angry crowd. There is speculation that the van is part of the attack, but the RUC says it was part of a police patrol, and that the officers sped off because they feared for their lives. Stone says he had arranged for a getaway car, driven by a UDA member, to pick him up on the hard shoulder of the motorway, but the driver allegedly “panicked and left.” By the time he reaches the motorway, he has seemingly run out of ammunition. He runs out onto the road and tries to stop cars, but is caught by the crowd, beaten, and bundled into a hijacked vehicle. Armed RUC officers in Land Rovers quickly arrive, “almost certainly saving his life.” They arrest him and take him to Musgrave Park Hospital for treatment of his injuries. The whole event is recorded by television news cameras.

That evening, angry youths in republican districts burn hijacked vehicles and attack the RUC. Immediately after the attack, the two main loyalist paramilitary groups—the UDA and the Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF)—deny responsibility. Sinn Féin and others “claimed that there must have been collusion with the security forces, because only a small number of people knew in advance of the reduced police presence at the funerals.”

Three days later, during the funeral of one of Stone’s victims, Caoimhín Mac Brádaigh, two British Army corporals, Derek Wood and David Howes, in civilian clothes and in a civilian car drive into the path of the funeral cortège, apparently by mistake. Many of those present believe the soldiers are loyalists intent on repeating Stone’s attack. An angry crowd surrounds and attacks their car. Corporal Wood draws his service pistol and fires a shot into the air. The two men are then dragged from the car before being taken away, beaten and shot dead by the IRA. The incident is often referred to as the corporals killings and, like the attack at Milltown, much of it is filmed by television news cameras.

In March 1989, Stone is convicted for the three murders at Milltown, for three paramilitary murders before, and for other offences, receiving sentences totaling 682 years. Many hardline loyalists see him as a hero, and he becomes a loyalist icon. After his conviction, an issue of the UDA magazine Ulster is devoted to Stone, stating that he “stood bravely in the middle of rebel scum and let them have it.” Apart from time on remand spent in Crumlin Road Gaol, he spends all of his sentence in HM Prison Maze. He is released after serving 13 years as a result of the Good Friday Agreement.

In November 2006, Stone is charged with attempted murder of Martin McGuinness and Gerry Adams, having been arrested attempting to enter the Parliament Buildings at Stormont while armed. He is subsequently convicted and sentenced to a further 16 years imprisonment. He is released on parole in 2021.