William Congreve, English playwright, satirist and poet, dies at his home in Surrey Street, London, on January 19, 1729.

Congreve is born on January 24, 1670, at Bardsley, West Yorkshire, England, the son of William Congreve, an army officer, and Mary Browning of Doncaster. In 1674, his father gains a commission as lieutenant in the army in Ireland, and moves with his family to the garrison port of Youghal, County Cork, where they remain until 1678. After a brief period at Carrickfergus, they move in 1681 to Kilkenny, where his father is assigned to the Duke of Ormond‘s regiment. This service entitles Congreve to a free education at the renowned Kilkenny College, where Jonathan Swift is also a student, and where he receives an excellent schooling in classics. He forms a lasting friendship with another pupil, Joseph Kelly, a lawyer and MP for Doneraile (1705–13), with whom he later maintains a lengthy correspondence. In April 1686, he enters Trinity College Dublin (TCD) as a classical scholar and, again like Swift, is taught by St. George Ashe. It seems likely that his degree is disrupted by the political upheaval of 1688 as the college is forced to close in 1689 and his BA is not recorded.

At this point, Congreve leaves Ireland and spends the spring and summer of 1689 with relatives in Staffordshire. He subsequently moves to London, and in March 1691 enters the Middle Temple. He is not assiduous in his legal studies, preferring to socialise with intellectuals and writers, notably John Dryden, to pursue literary projects. In 1692, under the pseudonym “Cleophil,” he published Incognita, or, Love and Duty Reconciled, a romantic novella reputedly written while he is a student in Dublin. He also contributes some verse to Charles Gildon‘s Miscellany (1692), as well as two translations from Homer and three odes to Dryden’s Examen poeticum (1693). Dryden evidently thinks highly of the young writer, and with his advice and approbation Congreve’s first play, The Old Batchelor, is recommended by the Irish playwright Thomas Southerne to Thomas Davenant, manager of the Theatre Royal, Drury Lane. A fast-paced and witty comedy, concerning amorous appetites, The Old Batchelor is accepted and opens on March 9, 1693, to popular acclaim, enjoying an unusually long run of fourteen nights. Among the cast are Thomas Doggett, still relatively unknown, as Fondlewife, and a young English actress and singer, Anne Bracegirdle as Amarinta, with whom Congreve falls in love and begins a prolonged relationship. The play is dedicated to his friend Charles Boyle, eldest son of Richard Boyle, 1st Earl of Burlington, whose estates Congreve’s father had begun to manage in 1690.

After this early success, Congreve is dismayed by the poor reception of his next play, a domestic comedy with dark undertones entitled The Double Dealer, which is staged in December 1693 and criticised as immoral and unflattering in its representation of women. Its popularity improves somewhat when Mary II, Queen of England, soon after its undistinguished debut, commands a performance. When the queen dies the following year, Congreve eulogises her in The Mourning Muse of Alexis, a Pastoral. Regarded by contemporaries as his finest literary work, it is rewarded by a gift of £100 from King William III. Production of his next play is delayed by the revolt of the Drury Lane actors against the management of Christopher Rich. Congreve supports the actors and their petition to the Lord Chamberlain to reopen the theatre at Lincoln’s Inn Fields. When their request is granted, the renovated theatre opens on April 30, 1695, with Congreve’s enduring romantic comedy Love for Love, and the playwright being made a shareholder in the new company. A characteristically witty and well-plotted comedy, the production of Love for Love is particularly notable for Doggett’s sparkling performance as Sailor Ben. Congreve’s dramatic success also brings political advancement, as he receives his first government appointment as commissioner for hackney coaches.

Congreve returns to Ireland for most of 1696, where, with Southerne, he receives an MA from TCD, and probably visits his parents, then living at Lismore Castle, County Waterford. He also begins work on a tragedy entitled The Mourning Bride, which becomes an instant hit at Lincoln’s Inn Fields when it is first performed in February 1697 and running for thirteen nights. Despite his considerable success and popularity, he is deeply disconcerted by Jeremy Collier‘s aggressively anti-theatrical pamphlet, Short View of the Immorality and Profaneness of the English Stage (1698), which targets John Vanbrugh, Dryden, and Congreve. He is stung into a response, publishing Amendments of Mr. Collier’s False and Imperfect Citations (1698), which eloquently defends his dramatic methodology, but is rendered less effective by an emotional and ill-judged tone. His theatrical acumen seems to be at odds with the times, for in the dedication to his next play, The Way of the World, he observes that “little of it was prepar’d for that general taste which seems now to be predominant in the pallats of our audience.” Nevertheless, he is still bitterly disappointed by the disparaging response to its first performance on March 12, 1700. Dryden, however, realises the merit of the play, which is now recognised as Congreve’s masterpiece and a landmark in the dramatic tradition of the comedy of manners.

Disheartened, Congreve abandons play-writing, but he maintains his theatrical connections and embarks upon several collateral projects, producing a libretto for The Judgement of Paris (1701), and collaborating with Vanbrugh and the poet William Walsh on a translation of Molière‘s Monsieur de Pourceaugnac, staged as Squire Trelooby at the Lincoln’s Inn Fields theatre in 1704. Less successfully, he makes an ill-advised investment with Vanbrugh in a new theatre and opera house in the Haymarket, from which he withdraws with financial losses in 1705. His opera libretto Semele, written for the opening of the new theatre, is not performed until 1744, when it is scored by George Frideric Handel, though John Eccles writes a score in 1707 which remains unperformed until 1972. In the early 1700s his relationship with Anne Bracegirdle falters, though they remain lifelong friends.

In 1710, Congreve publishes The Works of Mr. William Congreve in three volumes. He continues throughout his life to write poetry, ballads, essays, and other miscellaneous pieces. He remains active and influential in literary and theatrical circles, often assisting young writers such as Charles Hopkins, son of Ezekiel Hopkins, Bishop of Derry, and Alexander Pope, who dedicates to him The Iliad (1715). Financially, however, he becomes increasingly dependent upon various minor government posts. He belongs for many years to the celebrated Kit-Cat Club, alongside such prominent writers, wits, and whigs as Richard Boyle, 2nd Earl of Cork, Richard Steele, Joseph Addison, Walsh, and Vanbrugh. Through the good offices of his friend Jonathan Swift, he retains his government position as Commissioner of Wines during the Tory administration of 1710–14. His party loyalty is rewarded in 1714 when he receives a lucrative government appointment as Secretary of the island of Jamaica. His personal life also improves around this time, as a friendship with Lady Henrietta Godolphin develops into a love affair that lasts for the rest of his life. They have one daughter, Mary (1723–64).

Congreve suffers for much of his life from gout and failing eyesight. These afflictions worsen with age, though friends remark that his cheerful temper survived unaffected. He is involved in a coach accident in September 1728, and dies January 19, 1729, at his home in Surrey Street, likely from a related injury. He names Francis Godolphin, 2nd Earl of Godolphin, his lover’s husband, as his executor, and bequeaths almost his entire estate to Henrietta, thereby discreetly leaving his property to his daughter. He is buried in Poet’s Corner, Westminster Abbey, on January 26.

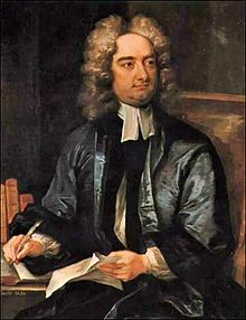

Letters and manuscripts of Congreve are held in the Bodleian Library at the University of Oxford, the British Library, London, and the National Archives of Scotland. Several likenesses are in the National Portrait Gallery, London, including the portrait in oils shown above by Sir Godfrey Kneller (1709).

(From: “Congreve, William” by Sinéad Sturgeon, Dictionary of Irish Biography, http://www.dib.ie, October 2009; Pictured: Portrait of William Congreve (1709) by Sir Godfrey Kneller)