(Michael) Leo Whelan, portrait and genre painter, dies from leukemia on November 6, 1956, at the Mater private nursing home in Dublin.

Whelan is born on January 17, 1892, at 20 St. George’s Villas, Fairview, Dublin, one of two sons and three daughters of Maurice Whelan, a draper, of County Kerry ancestry, and Mary Whelan (née Cruise), from County Roscommon. The family subsequently moves to 65 Eccles Street, where his parents operated a small hotel. Educated at Belvedere College, Dublin, he then attends the Dublin Metropolitan School of Art (DMSA) (1908–14), where he is a student of William Orpen, who has a huge influence on his artistic style. His fellow students at the school include Patrick Tuohy and Séan Keating.

Whelan is awarded many prizes in the Royal Dublin Society (RDS) Taylor art competitions, including one in 1912 for a portrait of his sister Lena, entitled On the Moors, rendered in a strongly academic technique. In 1916, he wins the Taylor scholarship for the Royal Hibernian Academy (RHA) schools for his finest early work, The Doctor’s Visit, an adroitly executed composition of contrasting shadows and light. Typical of many of his genre interiors, the painting depicts a room in the family home, with relatives as models: Whelan’s mother sits by the bed watching over his ill cousin, while his sister, dressed in a Mater hospital nurse’s uniform, is in the background opening the door for the doctor. The subtly evoked atmosphere of restrained emotion foreshadowed a hallmark of his mature style.

Whelan exhibits annually at the RHA for forty-five years (1911–56), averaging six works per year. He is elected an RHA associate in 1920, becoming a full member in 1924. He participates in the Exposition d’art irlandais at the Galerie Barbazanges in Paris in 1922. A visiting teacher at the RHA schools in 1924, he also teaches in the DMSA for a time. He has studios at 64 Dawson Street (1914–27) and 7 Lower Baggot Street (1931–56). Beginning in the 1910s, he receives regular commissions for portraits, constituting his primary source of income. Having become the family’s main breadwinner following his parents’ deaths in the 1920s, he concentrates most of his production on this lucrative activity, portraying numerous leading figures in the spheres of politics, academia, religion, society, medicine, and law.

Coming from a family of militant nationalist sympathies, in 1922 he begins a large group portrait, GHQ Staff of the Pre-Treaty IRA, including Michael Collins, Richard Mulcahy, Rory O’Connor, Liam Mellows and nine others, composed from individual studies of the men rendered during clandestine sittings in his home and studio. The painting, which he leaves unfinished, is in McKee Barracks, Dublin. He receives special praise for his portraits of John Henry Bernard, Provost of Trinity College Dublin (TCD) and of Louis Claude Purser, TCD vice-provost. The latter is awarded a medal at the 1926 Tailteann Games. He exhibits seventeen paintings at the Royal Society of Portrait Painters, London, of which he is a member, and shows two works at the Royal Academy of Arts, London. His 1929 portrait of John McCormack, one of his major patrons, is presented by the tenor’s family some fifty years later to the National Concert Hall, Dublin.

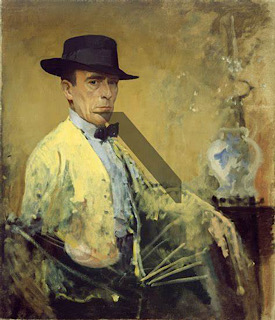

Situated securely in the academic tradition, in most of his portraits Whelan favours a sombre, restricted palette, with the sitter placed, in grave demeanour, against a monotone background with few accessories. In a 1943 interview he asserts that twentieth-century portraiture suffers from the drabness of modern costume, for which the artist must compensate by careful rendition of the subject’s hands. He tends to depart from his prevailing portrait style when painting women, whom he characteristically depicts in meticulously observed interiors, a notable example being his portrait of Society hostess Gladys Maccabe (c.1946; NGI).

Whelan’s commercial concentration on portraiture notwithstanding, he expresses his true talent in genre compositions, especially kitchen interiors, in which he emulates the technique of the Dutch painter Johannes Vermeer. Two of the most accomplished of these depict his sister Frances in the basement kitchen of the family home: The Kitchen Window (1927; Crawford Art Gallery, Cork) demonstrates a particularly skillful use of light, while Interior of a Kitchen (1935) is notable for the dexterous handling of objects of varied shapes and textures. His genre works include both urban and rural scenes, with a distinctive interest in portraying occupations and other activities. Gypsy (1923), an Orpenesque composition of a shawled woman in a west-of-Ireland landscape with a caravan in the background, receives wide contemporary critical acclaim. Jer (c.1925), depicting a man seated by the fire in a cottage interior, is reproduced in J. Crampton Walker’s Irish Art and Landscape (1927). The Fiddler (c.1932), a naturalistic, sensitively characterised study, is first shown at an Ulster Academy exhibition at Stranmillis, Belfast. A Kerry Cobbler is reproduced in Twelve Irish Artists (1940), introduced by Thomas Bodkin, as among the works denoting the development of a distinctively Irish school of painting.

In 1929, Whelan designs the first Irish Free State commemorative stamp, a portrait of Daniel O’Connell for the centenary of Catholic emancipation. Commissioned by the Thomas Haverty trust to paint an incident from the life of Saint Patrick for the 1932 Eucharistic Congress, he executes The Baptism by St. Patrick of Ethna the Fair and Fedelmia the Ruddy, Daughters of the Ard Rí Laoghaire, a work highly conservative in style. He rapidly completes an oil study of the papal legate, Lorenzo Lauri, also for the Eucharistic Congress. He is represented in the art competitions at the 1932 Summer Olympics in Los Angeles. His depiction of Saint Brigid, shown at the Academy of Christian Art exhibition (1940), becomes a familiar image owing to the wide circulation of reproductions.

Whelan’s political portraits are influential in creating a strong, assured image of the newly formed Irish state, and thus retain an historical significance. His posthumous portrait, The Late General Michael Collins, exhibited at the RHA in 1943 and now held in Leinster House, is an iconic, heroic image of the fallen leader. His portraits of Arthur Griffith and Kevin O’Higgins – commissioned posthumously, as is the Collins, by Fine Gael – also hang in Leinster House, while that of John A. Costello, exhibited at the RHA in 1949, is now held in the King’s Inns, Dublin. He paints two presidents, Douglas Hyde and Seán T. O’Kelly, both works currently in Áras an Uachtaráin. A portrait of Éamon de Valera, painted in 1955 when the sitter is Leader of the Opposition, is in Leinster House. In 1954, he designs a second commemorative stamp, picturing a reproduction of a portrait bust of John Henry Newman, to mark the centenary of the Catholic University of Ireland.

Whelan is elected an honorary academician of both the Ulster Academy of Arts (1931), and the Royal Ulster Academy (1950). He becomes a member of the United Arts Club in 1934. As a representative of the RHA, he sits on the board of governors of the National Gallery of Ireland for many years, and is on the advisory committee of the Municipal Gallery of Modern Art. Unmarried, he resides until his death at the Eccles Street address, with two sisters who continue to manage the family hotel. He dies on November 6, 1956, from leukemia at the Mater private nursing home in Dublin. He is buried in Glasnevin Cemetery.

(From: “Whelan, (Michael) Leo,” by Carmel Doyle, Dictionary of Irish Biography, http://www.dib.ie, October 2009)