On November 18, 1926, George Bernard Shaw refuses to accept the Nobel Prize in Literature prize money of £7,000 awarded to him a year earlier. He says, “I can forgive Alfred Nobel for his invention of the explosive but only the devil can think of the Nobel Prize.”

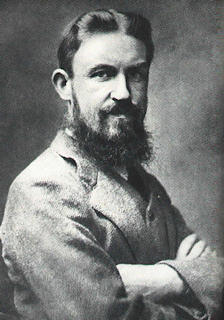

Shaw is born in Dublin on July 26, 1856, the third child of George Carr Shaw, a civil servant who later turns to a failed grain business to become an alcoholic, and Lucinda Elizabeth Shaw, a professional singer and sister of the famous opera singer Lucinda Frances. He is initially poor but is gifted with music and soon understands and loves the work of famous musicians and learns more about painting in Dublin. At the age of 15, he works as an apprentice and cashier for a real estate firm.

In 1876, Shaw follows his mother and two sisters to London. There he writes music reviews for newspapers to earn money, self-studies and actively participates in social activities. In 1884, he joins the founding of Fabian Society, an organization of British intellectuals advocating transition from capitalism to socialism by way of peace. From 1879 to 1883, he writes his first novel, Immaturity, and five other works that are not printed. An Unsocial Socialist is the first novel to be printed in 1887. Considered the father of “conceptual drama,” he begins writing plays in 1885, but achieves initial fame with Widowers’ Houses (1892). By 1903, his drama takes over the American and German stage, and in 1904 dominates the domestic stage. He becomes even more famous when Edward VII, the King of England, attends the performance of John Bull’s Other Island (1904), after which his drama spreads to European countries.

In addition, Shaw is also considered the best playwright in Britain at the time. He wants to use art to awaken people first to require changing the bourgeoisie order with all its institutions and customs. He emphasizes the educational function of the theater, but seeing the function of education is not an imposition from the playwright but arousing the aesthetic needs of the audience. The harsh problems of contemporary society such as the island’s predominant power, exploitative patterns, and the poverty of the people lead to social evils clearly reflected in his drama. His drama style tends to be satirical, sarcastic, finding its way to truth through paradoxes.

Shaw’s youngest dream is to earn a sum of money, then marry a wealthy wife. However, before becoming so wealthy that he can spend $ 35,000 on charity and enough money to travel around the world, he goes through many years of hardship. In the first nine years of his career, he receives only $30 USD in royalties. He is so poor that he does not even have the toll to get his manuscript to publishers. His clothes are tattered, his shoes open. All of his spending comes from his mother’s allowance. When he gets his name and remembers the miserable days, he often frowns, “I should have supported my family, the results are the opposite. I have never done anything for my family, and my mother has to work, raising me even though I was an adult.” Shaw, however, decides not to give up writing.

Realizing that, Shaw looks at the real royalties by publishing novels and the journey to the desired destination seems far away. He then turns to writing plays. He calculates that if the script is made public, the author will have revenue through the number of tickets issued and the number of shows. At the same time, the name of the author is also quickly known to the public. On the other hand, he says, only theater can “awaken people before the change of modern social order with all its institutions and customs.” He also judges that in addition to entertainment functions, the drama also contains the function of education, through arousing the aesthetic needs of the audience. He does not hesitate to bring to the stage all the most pressing issues of contemporary society such as the money’s inertia, the poverty of the people, and the social evils.

Saint Joan (1923) is judged to be the culmination of Shaw’s writing career. It is performed throughout European stages and is very popular. Two years after the release of Saint Joan, he is awarded the Nobel Prize for “the ideological and highly humanistic compositions, especially the spectacular satirical plays, combined with looks. Strange beauty of poetry.” When notified of his winning of the Nobel Prize, he humorously says, “The Nobel Prize for literature is like a float thrown to a swimmer.” Although he thinks he is the “swimmer to the shore,” he never leaves the pen. Thirteen years after receiving the Nobel Prize, Pygmalion, a script he wrote in 1912, is made into a film and receives the Academy Award for Best Adapted Screenplay.

In terms of scenario remuneration, Shaw receives an average of $100,000 a year, enough to spend on life, “reproduce” writing and traveling. It is only possible to marry a wealthy wife until the age of 40 years old. He always thinks that he “has no marriage status because he always worries others.” In terms of form, he is not very attractive because of his skinny body, but watching as the sisters do not allow him to carry out his intention to preserve his “absolute freedom.” Many beautiful female actors actively proclaim marriage proposal to Shaw, but he always uses humorous sentences to refuse.

Describing the George Bernard Shaw, Albert Einstein‘s physical genius after having met him has to say, “There are rare people who are so independent that they can see the weaknesses and absurdities of contemporaries. and at the same time do not let me get into it, but even so, when I encounter the hardships of life, these lonely people often lose their courage in helping humanity, with subtle humor and gentleness, can enthrall contemporaries and deserve to be torchbearers on the way of art’s unfavorable ways, today, with a passionate affection, I salute celebrate the biggest teacher on that path – the one who taught us and made us all feel happy.” It is a rare meeting of two great people in London in the fall of 1930.

(From: “November 18, 1926 – George Bernard Shaw refuses to receive a Nobel prize,” ScienceInfo.net, updated December 17, 2018)