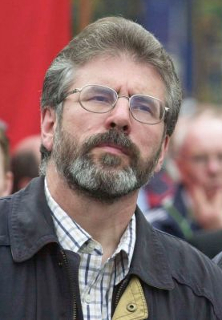

On October 27, 2002, after comments by the British prime minister Tony Blair that the continued existence of the Irish Republican Army (IRA) is an obstacle to rescuing the Northern Ireland peace process, Sinn Féin leader Gerry Adams says the IRA is never going to disband in response to ultimatums from the British government and from unionists.

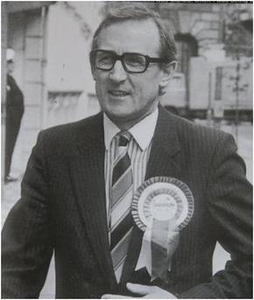

Nationalists throughout Ireland wish to see the end of the IRA. In a response to a major speech by Adams, Mark Durkan, leader of the Social Democratic and Labour Party (SDLP), says IRA activity is playing into the hands of anti-Agreement unionists and calls on the IRA to cease all activity.

Adams tells elected Sinn Féin representatives from both sides of the Irish border in Monaghan that he can envision a future without the IRA. He also admits that “alleged” IRA activities are boosting the cause of those opposing the Northern Ireland peace process. However, he also tells Tony Blair that the IRA will never disband in response to ultimatums.

“He needs to recognise, however, that the Agreement requires an end to paramilitarism and that nationalists throughout this island fervently want one. It is time that republicans took heed of their call.”

The former Deputy First Minister in the devolved administration at Stormont says he welcomes Adams’ recognition that IRA activity is exacerbating the difficulties within unionism. “The reality is that IRA activity is playing right into the hands of anti-Agreement unionists. And letting the nationalist community badly down,” he said.

“It is also welcome that Gerry Adams has begun to recognise Sinn Féin’s credibility crisis. Too often republican denials have proved to be false in the past – be it over Colombia or Florida. This too has served only to create distrust and destabilise the Good Friday Agreement,” he adds.

In a major speech billed by his party as a considered response to the Prime Minister’s demand for an end to Republican-linked violence, Adams declares “Our view is that the IRA cessations effectively moved the army out of the picture – and allowed the rest of us to begin an entirely new process.” His speech is understood to have been handed in advance to both the British and Irish governments.

Adams says the continued IRA ceasefire and decommissioning initiatives demonstrated the organisation’s commitment to the peace process. “I do not pretend to speak for the army (IRA) on these matters, but I do believe that they are serious about their support for a genuine peace process. They have said so. I believe them,” he said. He adds, “The IRA is never going to respond to ultimatums from the British government or David Trimble.”

Fianna Fáil leader Bertie Ahern later says he welcomes and is encouraged by many aspects of Adams’ speech. He says the Sinn Féin leader’s strong statement of determination to keep the peace process intact and the recognition of the need to bring closure to all the key issues is a positive contribution at this difficult time in the Northern Ireland peace process.

(From the Irish Examiner, October 27, 2002)