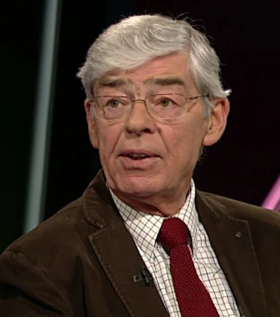

Alan Martin Dukes, former Fine Gael politician, is born in Drimnagh, Dublin, on April 20, 1945. He holds several senior government positions and serves as a Teachta Dála (TD) from 1981 to 2002. He is one of the few TDs to be appointed a minister on their first day in the Dáil.

His father, James F. Dukes, is originally from Tralee, County Kerry, and is a senior civil servant and the founding chairman and chief executive of the Higher Education Authority (HEA), while his mother is from near Ballina, County Mayo.

The Dukes family originally comes from the north of England. His grandfather serves with the Royal Engineers in World War I and settles in County Cork and then County Kerry afterward where he works with the Post Office creating Ireland’s telephone network.

Dukes is educated by the Christian Brothers at Coláiste Mhuire, Dublin, and is offered several scholarships for third level on graduation, including one for the Irish language. His interest in the Irish language continues to this day, and he regularly appears on Irish-language television programmes.

On leaving school he attends University College Dublin (UCD), where he captains the fencing team to its first-ever Intervarsity title.

Dukes becomes an economist with the Irish Farmers’ Association (IFA) in Dublin in 1969. After Ireland joins the European Economic Community (EEC) in 1973, he moves to Brussels where he is part of the IFA delegation. In this role, he is influential in framing Ireland’s contribution to the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP). He is appointed as chief of staff to Ireland’s EEC commissioner Richard Burke, a former Fine Gael politician.

In the 1979 European Parliament election, Dukes stands as a Fine Gael candidate in the Munster constituency. He has strong support among the farming community, but the entry of T. J. Maher, a former president of the IFA, as an independent candidate hurts his chances of election. Maher tops the poll.

He stands again for Fine Gael at the 1981 Irish general election in the expanded Kildare constituency, where he wins a seat in the 22nd Dáil. On his first day in the Dáil, he is appointed Minister for Agriculture by the Taoiseach, Garret FitzGerald, becoming one of only eight TDs so appointed. He represents Kildare for 21 years.

This minority Fine Gael–Labour Party coalition government collapses in February 1982 on the budget but returns to power with a working majority in December 1982. Dukes is again appointed to cabinet, becoming Minister for Finance less than two years into his Dáil career.

He faces a difficult task as finance minister. Ireland is heavily in debt while unemployment and emigration are high. Many of Fine Gael’s plans are deferred while the Fine Gael–Labour Party coalition disagrees on how to solve the economic crisis. The challenge of addressing the national finances is made difficult by electoral arithmetic and a lack of support from the opposition Fianna Fáil party led by Charles Haughey. He remains in the Department of Finance until a reshuffle in February 1986 when he is appointed Minister for Justice.

Fine Gael fails to be returned to government at the 1987 Irish general election and loses 19 of its 70 seats, mostly to the new Progressive Democrats. Outgoing Taoiseach and leader Garret FitzGerald steps down and Dukes is elected leader of Fine Gael, becoming Leader of the Opposition.

This is a difficult time for the country. Haughey’s Fianna Fáil runs on promises to increase spending and government services, and attacking the cutbacks favoured by Fine Gael. However, on taking office, the new Taoiseach and his finance minister Ray MacSharry immediately draw up a set of cutbacks including a spate of ward and hospital closures. This presents a political opportunity for the opposition to attack the government.

However, while addressing a meeting of the Tallaght Chamber of Commerce, Dukes announces, in what becomes known as the Tallaght Strategy that: “When the government is moving in the right direction, I will not oppose the central thrust of its policy. If it is going in the right direction, I do not believe that it should be deviated from its course, or tripped up on macro-economic issues.”

This represents a major departure in Irish politics whereby Fine Gael will vote with the minority Fianna Fáil Government if it adopts Fine Gael’s economic policies for revitalising the economy. The consequences of this statement are huge. The Haughey government is able to take severe corrective steps to restructure the economy and lay the foundations for the economic boom of the nineties. However, at a snap election in 1989, Dukes does not receive electoral credit for this approach, and the party only makes minor gains, gaining four seats. The outcome is the first-ever coalition government for Fianna Fáil, whose junior partner is the Progressive Democrats led by former Fianna Fáil TD Desmond O’Malley.

The party’s failure to make significant gains in 1989 leaves some Fine Gael TDs with a desire for a change at the top of the party. Their opportunity comes in the wake of the historic 1990 Irish presidential election. Fine Gael chooses Austin Currie TD as their candidate. He had been a leading member of the Northern Ireland Civil Rights Association (NICRA) movement in the 1960s and had been a member of the Social Democratic and Labour Party (SDLP) before moving south.

Initially, Fianna Fáil’s Brian Lenihan Snr is the favourite to win. However, after several controversies arise, relating to the brief Fianna Fáil administration of 1982, and Lenihan’s dismissal as Minister for Defence midway through the campaign, the Labour Party’s Mary Robinson emerges victorious. To many in Fine Gael, the humiliation of finishing third is too much to bear and a campaign is launched against Dukes’ leadership. He is subsequently replaced as party leader by John Bruton.

Bruton brings Dukes back to the front bench in September 1992, shortly before the November 1992 Irish general election. In February 1994, Dukes becomes involved in a failed attempt to oust Bruton as leader and subsequently resigns from the front bench. Bruton becomes Taoiseach in December 1994 and Dukes is not appointed to cabinet at the formation of the government.

In December 1996, Dukes returns as Minister for Transport, Energy and Communications following the resignation of Michael Lowry. At the 1997 Irish general election, he tops the poll in the new Kildare South constituency, but Fine Gael loses office. He becomes Chairman of the Irish Council of the European Movement. In this position, he is very involved in advising many of the Eastern European countries who are then applying to join the European Union.

In 2001, Dukes backs Michael Noonan in his successful bid to become leader of Fine Gael.

After 21 years, Dukes loses his Dáil seat at the 2002 Irish general election. This contest sees many high-profile casualties for Fine Gael, including Deputy Leader Jim Mitchell, former deputy leader Nora Owen and others. Many local commentators feel that Dukes’ loss is due to a lack of attention to local issues, as he is highly involved in European projects and has always enjoyed a national profile.

He retires from frontline politics in 2002 and is subsequently appointed Director General of the Institute of International and European Affairs. He remains active within Fine Gael and serves several terms as the party’s vice-president. From 2001 to 2011, he is President of the Alliance française in Dublin, and in June 2004, the French Government appoints him an Officer of the Legion of Honour. In April 2004, he is awarded the Commander’s Cross of the Order of Merit of the Republic of Poland.

In December 2008, Dukes is appointed by Finance Minister Brian Lenihan Jnr as a public interest director on the board of Anglo Irish Bank. The bank is subsequently nationalised, and he serves on the board until the Irish Bank Resolution Corporation (IBRC) is liquidated in 2013.

From 2011 to 2013, Dukes serves as chairman of the Board of Irish Guide Dogs for the Blind. In 2011, he founds the think tank Asia Matters, which inks an agreement with the Chinese People’s Association for Friendship with Foreign Countries in May 2019.

Dukes has lived in Kildare since first being elected to represent the Kildare constituency in 1981. His wife Fionnuala (née Corcoran) is a former local politician and serves as a member of Kildare County Council from 1999 until her retirement in 2009. She serves as Cathaoirleach of the council from 2006 to 2007, becoming only the second woman to hold the position in the body’s one-hundred-year history. They have two daughters.