Arthur Wolfe, 1st Viscount Kilwarden KC, Anglo-Irish peer, politician and judge, who held office as Lord Chief Justice of Ireland, is born on January 19, 1739, at Forenaughts House, Naas, County Kildare.

Wolfe is the eighth of nine sons born to John Wolfe (1700–60) and his wife Mary (d. 1763), the only child and heiress of William Philpot, a successful merchant at Dublin. One of his brothers, Peter, is the High Sheriff of Kildare, and his first cousin Theobald is the father of the poet Charles Wolfe.

Wolfe is educated at Trinity College Dublin, where he is elected a Scholar, and at the Middle Temple in London. He is called to the Irish Bar in 1766. In 1769, he marries Anne Ruxton (1745–1804) and, after building up a successful practice, takes silk in 1778. He and Anne have four children, John, Arthur, Mariana and Elizabeth.

In 1783, Wolfe is returned as Member of Parliament for Coleraine, which he represents until 1790. In 1787, he is appointed Solicitor-General for Ireland, and is returned to Parliament for Jamestown in 1790.

Appointed Attorney-General for Ireland in 1789, Wolfe is known for his strict adherence to the forms of law, and his opposition to the arbitrary measures taken by the authorities, despite his own position in the Protestant Ascendancy. He unsuccessfully prosecutes William Drennan in 1792. In 1795, Lord Fitzwilliam, the new Lord Lieutenant of Ireland, intends to remove him from his place as Attorney-General to make way for George Ponsonby. In compensation, Wolfe’s wife is created Baroness Kilwarden on September 30, 1795. However, the recall of Fitzwilliam enables Wolfe to retain his office.

In January 1798, Wolfe is simultaneously returned to Parliament for Dublin City and Ardfert. However, he leaves the Irish House of Commons when he is appointed Chief Justice of the Kings Bench for Ireland and created Baron Kilwarden on July 3, 1798.

After the Irish Rebellion of 1798, Wolfe becomes notable for twice issuing writs of habeas corpus on behalf of Wolfe Tone, then held in military custody, but these are ignored by the army and forestalled by Tone’s suicide in prison. In 1795 he had also warned Tone and some of his associates to leave Ireland to avoid prosecution. Tone’s godfather, Theobald Wolfe of Blackhall (the father of Charles Wolfe), is Wolfe’s first cousin, and Tone may have been Theobald’s natural son. These attempts to help a political opponent are unique at the time.

After the passage of the Acts of Union 1800, which he supports, Wolfe is created Viscount Kilwarden on December 29, 1800. In 1802, he is appointed Vice-Chancellor of the University of Dublin.

In 1802 Wolfe presides over the case against Town Major Henry Charles Sirr in which the habitual abuses of power used to suppress rebellion are exposed in court.

In the same year Wolfe orders that the well-known Catholic priest Father William Gahan be imprisoned for contempt of court. In a case over the disputed will of Gahan’s friend John Butler, 12th Baron Dunboyne, the priest refuses to answer certain questions on the ground that to do so would violate the seal of the confessional, despite a ruling that the common law does not recognize the seal of the confessional as a ground for refusing to give evidence. The judge apparently feels some sympathy for Gahan’s predicament, as he is released from prison after only a few days.

During the Irish rebellion of 1803, Wolfe, who had never been forgiven by the United Irishmen for the execution of William Orr, is clearly in great danger. On the night of July 23, 1803, the approach of the Kildare rebels induces him to leave his residence, Newlands House, in the suburbs of Dublin, with his daughter Elizabeth and his nephew, Rev. Richard Wolfe. Believing that he will be safer among the crowd, he orders his driver to proceed by way of Thomas Street in the city centre. However, the street is occupied by Robert Emmet‘s rebels. Unwisely, when challenged, he gives his name and office, and he is rapidly dragged from his carriage and stabbed repeatedly with pikes. His nephew is murdered in a similar fashion, while Elizabeth is allowed to escape to Dublin Castle, where she raises the alarm. When the rebels are suppressed, Wolfe is found to be still alive and is carried to a watch-house, where he dies shortly thereafter. His last words, spoken in reply to a soldier who called for the death of his murderers, are “Murder must be punished; but let no man suffer for my death, but on a fair trial, and by the laws of his country.”

Wolfe is succeeded by his eldest son John Wolfe, 2nd Viscount Kilwarden. Neither John nor his younger brother Arthur, who dies in 1805, have male issue, and on John’s death in 1830 the title becomes extinct.

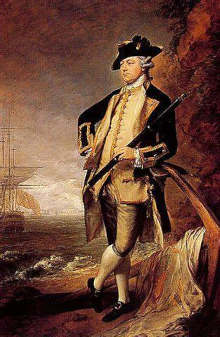

(Pictured: Portrait of Lord Chief Justice of Ireland, Arthur Wolfe (later Viscount Kilwarden) by Hugh Douglas Hamilton, between 1797 and 1800, Gallery of the Masters)