The Irish Confederation, an Irish nationalist independence movement, is established on January 13, 1847, by members of the Young Ireland movement who seceded from Daniel O’Connell‘s Repeal Association. Historian Theodore William Moody describes it as “the official organisation of Young Ireland.”

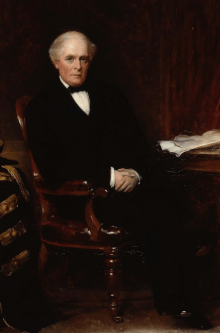

In June 1846, Sir Robert Peel‘s Tory Ministry falls, and the Whigs under Lord John Russell comes to power. Daniel O’Connell, founder of the Repeal Association which campaigns for a repeal of the Acts of Union 1800 between Great Britain and Ireland, simultaneously attempts to move the Association into supporting the Russell administration and English Liberalism.

The intention is that Repeal agitation is to be damped down in return for a profuse distribution of patronage through Conciliation Hall, home of the Repeal Association. On June 15, 1846, Thomas Francis Meagher denounces English Liberalism in Ireland saying that there is a suspicion that the national cause of Repeal will be sacrificed to the Whig government and that the people who are striving for freedom will be “purchased back into factious vassalage.” Meagher and the other “Young Irelanders” (an epithet of opprobrium used by O’Connell to describe the young men of The Nation newspaper), as active Repealers, vehemently denounce in Conciliation Hall any movement toward English political parties, be they Whig or Tory, so long as Repeal is denied.

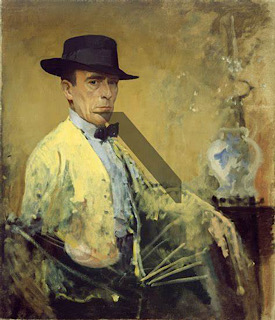

The “Tail” as the “corrupt gang of politicians who fawned on O’Connell” are named, and who hope to gain from the government places decide that the Young Irelanders must be driven from the Repeal Association. The Young Irelanders are to be presented as revolutionaries, factionists, infidels and secret enemies of the Church. For this purpose, resolutions are introduced to the Repeal Association on July 13 which declare that under no circumstances is a nation justified in asserting its liberties by force of arms. The Young Irelanders, as members of the association, have never advocated the use of physical force to advance the cause of repeal and oppose any such policy. Known as the “Peace Resolutions,” they declare that physical force is immoral under any circumstances to obtain national rights. Meagher agrees that only moral and peaceful means should be adopted by the Association, but if it is determined that Repeal cannot be carried by those means, a no less honourable one he would adopt though it be more perilous. The resolutions are again raised on July 28 in the Association and Meagher then delivers his famous “Sword Speech.”

Addressing the Peace Resolutions, Meagher holds that there is no necessity for them. Under the existing circumstances of the country, any provocation to arms will be senseless and wicked. He dissents from the Resolutions because by assenting to them he would pledge himself to the unqualified repudiation of physical force “in all countries, at all times, and in every circumstance.” There are times when arms will suffice, and when political amelioration calls for “a drop of blood, and many thousand drops of blood.” He then “eloquently defended physical force as an agency in securing national freedom.” Having been at first semi-hostile, Meagher carries the audience to his side and the plot against the Young Irelanders is placed in peril of defeat. Observing this he is interrupted by O’Connell’s son, John, who declares that either he or Meagher must leave the hall. William Smith O’Brien then protests against John O’Connell’s attempt to suppress a legitimate expression of opinion, and leaves with other prominent Young Irelanders, and never returns.

After negotiations for a reunion have failed, the seceders decide to establish a new organisation which is to be called the Irish Confederation. Its founders determine to revive the uncompromising demand for a national Parliament with full legislative and executive powers. They are resolute on a complete prohibition of place-hunting or acceptance of office under the existing Government. They wish to return to the honest policy of the earlier years of the Repeal Association, and are supported by the young men, who have shown their repugnance for the corruption and insincerity of Conciliation Hall by their active sympathy with the seceders. There are extensive indications that many of the previously Unionist class, in both the cities and among land owners, are resentful of the neglect of Irish needs by the British Parliament since the famine began. What they demand is vital legislative action to provide both employment and food, and to prevent all further export of the corn, cattle, pigs and butter which are still leaving the country. On this there is a general consensus of Irish opinion according to Dennis Gwynn, “such as had not been known since before the Act of Union.”

The first meeting of the Irish Confederation takes place in the Rotunda, Dublin, on January 13, 1847. The chairperson for the first meeting is John Shine Lawlor, the honorary secretaries being John Blake Dillon and Charles Gavan Duffy. Duffy is later replaced by Meagher. Ten thousand members are enrolled, but of the gentry there are very few, the middle class stand apart and the Catholic clergy are unfriendly. In view of the poverty of the people, subscriptions are purely voluntary, the founders of the new movement bearing the cost themselves if necessary.

In the 1847 United Kingdom general election, three Irish Confederation candidates stand – Richard O’Gorman in Limerick City, William Smith O’Brien in County Limerick and Thomas Chisholm Anstey in Youghal. O’Brien and Anstey are elected.

Following mass emigration by Irish people to England, the Irish Confederation then organises there also. There are more than a dozen Confederate Clubs in Liverpool and over 700 members of 16 clubs located in Manchester and Salford.