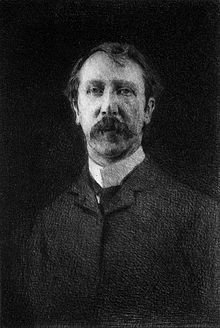

John Millington Synge, a leading figure in the Irish Literary Revival, dies in Dublin, on March 24, 1909. He is a poetic dramatist of great power who portrays the harsh rural conditions of the Aran Islands and the western Irish seaboard with sophisticated craftsmanship.

Synge is born in Newtown Villas, Rathfarnham, County Dublin, on April 16, 1871. He is the youngest son in a family of eight children. His parents are members of the Protestant upper middle class. His father, John Hatch Synge, who is a barrister, comes from a family of landed gentry in Glanmore Castle, County Wicklow.

Synge is born in Newtown Villas, Rathfarnham, County Dublin, on April 16, 1871. He is the youngest son in a family of eight children. His parents are members of the Protestant upper middle class. His father, John Hatch Synge, who is a barrister, comes from a family of landed gentry in Glanmore Castle, County Wicklow.

After studying at Trinity College and at the Royal Irish Academy of Music in Dublin, Synge pursues further studies from 1893 to 1897 in Germany, Italy, and France. In 1894 he abandons his plan to become a musician and instead concentrates on languages and literature. He meets William Butler Yeats while studying at the Sorbonne in Paris in 1896. Yeats inspires him with enthusiasm for the Irish renaissance and advises him to stop writing critical essays and instead to go to the Aran Islands and draw material from life. Already struggling against the progression of Hodgkin’s lymphoma which is untreatable at the time and eventually leads to his death, Synge lives in the islands during part of each year between 1898 and 1902, observing the people and learning their language, recording his impressions in The Aran Islands (1907) and basing his one-act plays In the Shadow of the Glen and Riders to the Sea (1904) on islanders’ stories. In 1905 his first three-act play, The Well of the Saints, is produced.

Synge’s travels on the Irish west coast inspire his most famous play, The Playboy of the Western World (1907). This morbid comedy deals with the moment of glory of a peasant boy who becomes a hero in a strange village when he boasts of having just killed his father but who loses the villagers’ respect when his father turns up alive. In protest against the play’s unsentimental treatment of the Irishmen’s love for boasting and their tendency to glamorize ruffians, the audience riots at its opening at Dublin’s Abbey Theatre. Riots of Irish Americans accompany its opening in New York City in 1911, and there are further riots in Boston and Philadelphia. Synge remains associated with the Abbey Theatre, where his plays gradually win acceptance, until his death. His unfinished Deirdre of the Sorrows, a vigorous poetic dramatization of one of the great love stories of Celtic mythology, is performed there in 1910.

John Millington Synge dies at the Elpis Nursing Home in Dublin on March 24, 1909, at the age of 37, and is buried in Mount Jerome Cemetery and Crematorium, Harold’s Cross, Dublin.

In the seven plays he writes during his comparatively short career as a dramatist, Synge records the colourful and outrageous sayings, flights of fancy, eloquent invective, bawdy witticisms, and earthy phrases of the peasantry from County Kerry to County Donegal. In the process he creates a new, musical dramatic idiom, spoken in English but vitalized by Irish syntax, ways of thought, and imagery.