On September 10, 1973, the Provisional Irish Republican Army (IRA) bombs the King’s Cross railway station and Euston railway station, two mainline railway stations in Central London. The blasts wound 13 civilians, some of whom are seriously injured, and also causes large-scale but superficial damage. This is a second wave of bombing attacks launched by the IRA in England in 1973 after the Old Bailey car bombing earlier in the year which had killed one and injured around 200 civilians.

In 1971, during the Troubles, after two years engaged in violence based on a defensive strategy in Irish communal districts of Northern Ireland, the Provisional IRA launches an offensive against the United Kingdom. At a meeting of the IRA Army Council in June 1972 the organization’s Chief of Staff, Seán Mac Stíofáin, first proposes making bombing attacks in England. The Army Council does not at first agree to the suggestion, but in early 1973 after its negotiations with the British Government for a truce the previous year had failed to advance the political objective of the removal of Northern Ireland from the United Kingdom by the application of the threat of violence, it re-engages its paramilitary campaign and sanctions Mac Stíofáin’s proposal. Mac Stíofáin had put the strategy forward on the basis that extending the urban paramilitary violence of the Northern Ireland state into England would help to relieve pressure being exerted by the British Army on the IRA’s strongholds of Irish communal support in districts in the province, such as west Belfast and Derry, by diverting British security strength from them back into England, while at the same time increasing strategic pressure upon the British Government to resolve the conflict by political concessions to the IRA’s demands. He also believes that a successful bombing campaign in London, as the capital city of the United Kingdom, will offer substantial propaganda value for paramilitary Irish Republicanism, and provide a morale boost to its supporters.

The effects of the previous 1973 Old Bailey bombing appear to give some credence to the idea of the propaganda value of extending violence into London as, although it is considered almost routine in Northern Ireland by the mid-1970s and draws only brief media notice, being carried out instead in London, a global capital city, makes the event world news headlines. However, although the bombing of the Old Bailey is successfully carried out, and gains media attention, increasing political pressure upon the British Government to address the issue of the conflict in Northern Ireland with more urgency, it is costly to the IRA, as 10 out of the 11-man active service unit that carry it out are arrested by the British police while trying to leave England before the bombs they had planted detonate. Drawing the tactical lesson that large teams are a security liability, for the second wave of bombings in England later in 1973, instead of sending a large team to carry it out with orders to withdraw back to Ireland immediately afterwards, smaller detached “cell” units of 3-4 personnel are sent to carry out the operation, with instructions to remain in England afterward and wage a campaign of bombings around England upon a variety of targets.

There are bombings on September 8, 1973, including one at London Victoria station which injures four civilians.

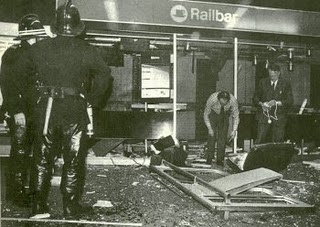

On September 10, 1973, a bomb (with no warning issued beforehand) explodes at King’s Cross railway station in the booking hall at 12:24 p.m. when a youth of around 16 to 17 years of age walks up to the entrance of the station’s old booking hall and throws a bag into it which contains a 3 lb. (1.4 kg) device, which detonates, shattering glass throughout the hall and throwing a baggage trolley several feet into the air. The youth then flees into the station’s crowd and escapes the scene.

Approximately 45 minutes after the attack at King’s Cross, after a telephone call warning to the Press Association five minutes beforehand by a man with an Irish accent, a second bomb detonates in a snack bar at Euston railway station, injuring another eight civilians. One witness at Euston says, “I saw a flash and suddenly people were being thrown through the air – it was a terrible mess, they were bleeding and screaming.” A total of 13 civilians are injured in the two attacks. The Metropolitan Police issue a photofit picture of a 5 ft. 2 in. (157 cm) tall youth they are seeking in regard to the King’s Cross attack.

On September 12, 1973, two more bombs explode, one in Oxford Street and another in Sloane Square, targeting retail shopping centres. Police subsequently announce that they are looking for five people in connection with this second wave of bomb attacks in England.

Judith Ward is later wrongly convicted of having been involved in the late 1973 London bombings, along with the M62 coach bombing. She is later acquitted. No one else is brought to trial for this IRA bombing campaign.