Mary Irvine, Irish judge who is the President of the Irish High Court between 2020 and 2022, is born on December 10, 1956, in Clontarf, Dublin. She first practiced as a barrister. She is a judge of the High Court between 2007 and 2014, a judge of the Court of Appeal from 2014 to 2019 and serves as a judge of the Supreme Court of Ireland from May 2019 until becoming President of the High Court on June 18, 2020. In addition to being the first woman to hold that position, she is the first judge to have held four judicial offices. She is an ex officio member of the Supreme Court and the Court of Appeal.

Irvine is born to John and Cecily Irvine, her father once being deputy director of RTÉ. She is educated at Mount Anville Secondary School, University College Dublin (UCD) and the King’s Inns. She is an international golf player, winning the Irish Girls Close Championship in 1975.

Irvine is called to the Bar in 1978 and becomes a Senior Counsel in 1996. She is the secretary of the Bar Council of Ireland in 1992. She is elected a Bencher of the King’s Inns in 2004.

Irvine specialises in medical law, appearing in medical negligence cases on behalf of and against health boards in actions. She is a legal advisor to an inquiry into deposit interest retention tax (DIRT) conducted by the Public Accounts Committee, along with future judicial colleagues Frank Clarke and Paul Gilligan. She represents the Congregation of Christian Brothers at the Commission to Inquire into Child Abuse.

Irvine’s practice also extends to constitutional law. As a junior counsel, she represents the plaintiff in Cahill v. Sutton in 1980 in the Supreme Court with seniors Niall McCarthy and James O’Driscoll. The case establishes the modern Irish law of standing for applicants to challenge the constitutional validity of statutes. She appears with Peter Kelly to argue on behalf the right of the unborn in a reference made by President of Ireland Mary Robinson under Article 26 of the Constitution to the Supreme Court in 1995 regarding the Information (Termination of Pregnancies) Bill 1995.

Irvine is appointed as a Judge of the High Court in June 2007. She is in charge of the High Court Personal Injuries list from 2009 to 2014 and subsequently becomes the second Chair of the Working Group on Medical Negligence and Periodic Payments, established by the President of the High Court.

Irvine is appointed to Court of Appeal on its establishment in October 2014. Some of her judgments on the Court of Appeal reduce awards given by lower courts for personal injuries compensation. She writes “most of the key” Court of Appeal judgments between 2015 and 2017 which have the effect of reducing awards arising from subsequent actions in the High Court.

Irvine is appointed to chair a statutory tribunal to conduct hearings and deal with cases related to the CervicalCheck cancer scandal in 2019. However, following her appointment as President of the High Court in 2020, she is unable to continue with the position.

On April 4, 2019, Irvine is nominated by the Government of Ireland as a Judge of the Supreme Court. She is appointed by the President of Ireland, Michael D. Higgins, on May 13, 2019. She writes decisions for the court in appeals involving planning law, the law of tort, intellectual property law, judicial review, and chancery law.

Irvine is appointed by Chief Justice Frank Clarke in 2019 to chair the Personal Injuries Guidelines Committee of the Judicial Council. The purpose of the committee is to review the levels of compensation issues in court cases arising out of personal injuries. Minister of State at the Department of Finance Michael W. D’Arcy writes a letter to congratulate her on her appointment and outlines his views that personal injuries awards in Ireland should be “recalibrated.” She responds to the letter by saying it is the not the committee’s duty to tailor its findings “in a manner favourable to any particular interest group.”

Following a cabinet meeting on June 12, 2020, it is announced that Irvine will be nominated to succeed Peter Kelly as President of the High Court. A three-person panel consisting of the Chief Justice Frank Clarke (later substituted by George Birmingham), the Attorney General Séamus Woulfe and a management consultant, Jane Williams, reviews applications for the position, before making recommendations to cabinet. The President of the Law Society of Ireland welcomes her appointment, describing her as an “outstandingly able judge.” She is the first woman to hold the role. As she is previously an ordinary judge of three courts, her appointment as President of the High Court makes her the first person to have held four judicial offices. She is appointed on June 18, 2020, and makes her judicial declaration on June 19.

Irvine takes over as president in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic in the Republic of Ireland. She issues guidelines for lawyers to negotiate personal injuries cases outside of court due to the backlog formed by delays in hearings. She issues a practice direction in July 2020 that face coverings are to be worn at High Court hearings. She criticises barristers and solicitors in October 2020 for not wearing masks in the Four Courts.

In Irvine’s first week as president, she presides over a three-judge division of the High Court in a case taken by a number of members of Seanad Éireann. The plaintiffs seek a declaration that the Seanad should sit even though the nominated members of Seanad Éireann have not been appointed. The court refuses the relief and finds for the State. In 2021, she also presides over a three-judge division on a Seanad Éireann voting rights case, where the plaintiff argues for the extension of voting rights to graduates of all third-level educational institutions and the wider population. The court finds against the plaintiff.

Irvine continues to sit in the Supreme Court following her appointment.

In April 2022, Irvine announces her intention to retire in July 2022. She retires on July 13, 2022, and is succeeded by David Barniville.

Irvine is formerly married to retired judge Michael Moriarty, with whom she has three children. Her only known son, Mark Moriarty, dies suddenly on August 19,2022.

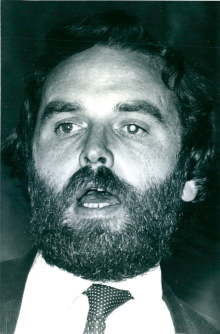

(Pictured: Justice Mary Irvine with the President of Ireland, Michael D. Higgins, on her appointment on the Supreme Court in 2019)