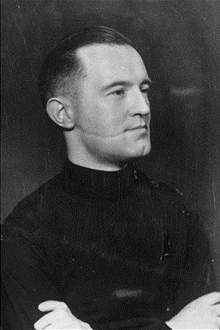

Ernesto “Che” Guevara, an Argentine Marxist revolutionary, physician, writer, guerrilla leader, diplomat, and military theorist of Spanish-Irish descent, is born on June 14, 1928, in Rosario, Santa Fe, Argentina. After his execution by the Bolivian army, he is regarded as a martyred hero by generations of leftists worldwide, and his image becomes an icon of leftist radicalism and anti-imperialism.

Guevara is the eldest of five children in a middle-class family of Spanish-Irish descent and leftist leanings. Although suffering from asthma, he excels as an athlete and a scholar, completing his medical studies in 1953. He spends many of his holidays traveling in Latin America, and his observations of the great poverty of the masses contributes to his eventual conclusion that the only solution lay in violent revolution. He comes to look upon Latin America not as a collection of separate nations but as a cultural and economic entity, the liberation of which would require an intercontinental strategy.

In particular, Guevara’s worldview is changed by a nine-month journey he begins in December 1951, while on hiatus from medical school, with his friend Alberto Granado. That trip, which begins on a motorcycle they call “the Powerful” (which breaks down and is abandoned early in the journey), takes them from Argentina through Chile, Peru, Colombia, and on to Venezuela, from which Guevara travels alone on to Miami, returning to Argentina by plane. During the trip he keeps a journal that is posthumously published under his family’s guidance as The Motorcycle Diaries: Notes on a Latin American Journey (2003) and adapted to film as The Motorcycle Diaries (2004).

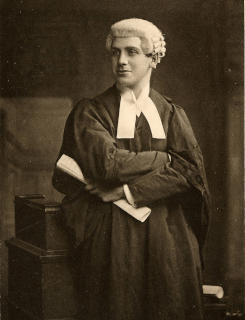

In 1953 Guevara goes to Guatemala, where Jacobo Árbenz heads a progressive regime that is attempting to bring about a social revolution. It is about this time he acquires his nickname, from a verbal mannerism of Argentines who punctuate their speech with the interjection “che.” The overthrow of the Árbenz regime in 1954 in a coup supported by the United States Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) persuades him that the United States will always oppose progressive leftist governments. This becomes the cornerstone of his plans to bring about socialism by means of a worldwide revolution. It is in Guatemala that he becomes a dedicated Marxist.

Guevara leaves Guatemala for Mexico, where he meets the Cuban brothers Fidel and Raúl Castro, political exiles who are preparing an attempt to overthrow the dictatorship of Fulgencio Batista in Cuba. He joins Fidel Castro’s 26th of July Movement, which lands a force of 81 men (including Guevara) in the Cuban Oriente Province on December 2, 1956. Immediately detected by Batista’s army, they are almost wiped out. The few survivors, including the wounded Guevara, reach the Sierra Maestra, where they become the nucleus of a guerrilla army. The rebels slowly gain in strength, seizing weapons from Batista’s forces and winning support and new recruits. Guevara had initially come along as the force’s doctor, but he has also trained in weapons use, and he becomes one of Castro’s most-trusted aides. Indeed, the complex Guevara, though trained as a healer, also, on occasion, acts as the executioner (or orders the execution) of suspected traitors and deserters.

After Castro’s victorious troops enter Havana on January 8, 1959, Guevara serves for several months at La Cabaña prison, where he oversees the executions of individuals deemed to be enemies of the revolution. He becomes a Cuban citizen, as prominent in the newly established Marxist government as he had been in the revolutionary army, representing Cuba on many commercial missions. He also becomes well known in the West for his opposition to all forms of imperialism and neocolonialism and for his attacks on U.S. foreign policy. He serves as chief of the Industrial Department of the National Institute of Agrarian Reform, president of the National Bank of Cuba (famously demonstrating his disdain for capitalism by signing currency simply “Che”), and Minister of Industries.

During the early 1960s, Guevara defines Cuba’s policies and his own views in many speeches and writings, notably “El socialismo y el hombre en Cuba” (1965; “Man and Socialism in Cuba,” 1967), an examination of Cuba’s new brand of communism, and a highly influential manual, La guerra de guerrillas (1960; Guerrilla Warfare, 1961). The last book includes his delineation of his foco theory (foquismo), a doctrine of revolution in Latin America drawn from the experience of the Cuban Revolution and predicated on three main tenets: 1) guerrilla forces are capable of defeating the army; 2) all the conditions for making a revolution do not have to be in place to begin a revolution, because the rebellion itself can bring them about; and 3) the countryside of underdeveloped Latin America is suited for armed combat.

Guevara expounds a vision of a new socialist citizen who would work for the good of society rather than for personal profit, a notion he embodies through his own hard work. Often he sleeps in his office, and, in support of the volunteer labour program he had organized, he spends his day off working in a sugarcane field. He grows increasingly disheartened, however, as Cuba becomes a client state of the Soviet Union, and he feels betrayed by the Soviets when they remove their missiles from the island without consulting the Cuban leadership during the Cuban Missile Crisis of 1962. He begins looking to the People’s Republic of China and its leader Mao Zedong for support and as an example.

In December 1964 Guevara travels to New York City, where he condemns U.S. intervention in Cuban affairs and incursions into Cuban airspace in an address to the United Nations General Assembly. Back in Cuba, increasingly disillusioned with the direction of the Cuban social experiment and its reliance on the Soviets, he begins focusing his attention on fostering revolution elsewhere. After April 1965 he drops out of public life. His movements and whereabouts for the next two years remain secret. It is later learned that he had traveled to what is now the Democratic Republic of the Congo with other Cuban guerrilla fighters in what proved to be a futile attempt to help the Patrice Lumumba battalion, which was fighting a civil war there. During that period he resigns his ministerial position in the Cuban government and renounces his Cuban citizenship. After the failure of his efforts in the Congo, he flees first to Tanzania and then to a safe house in a village near Prague.

In the autumn of 1966 Guevara goes to Bolivia, incognito (beardless and bald), to create and lead a guerrilla group in the region of Santa Cruz. After some initial combat successes, he and his guerrilla band find themselves constantly on the run from the Bolivian army. On October 9, 1967, the group is almost annihilated by a special detachment of the Bolivian army aided by CIA advisers. Guevara, who is wounded in the attack, is captured and shot. Before his body disappears to be secretly buried, his hands are cut off. They are preserved in formaldehyde so that his fingerprints can be used to confirm his identity.

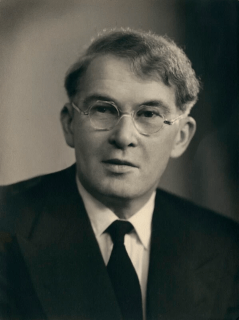

In 1995 one of Guevara’s biographers, Jon Lee Anderson, announces that he had learned that Guevara and several of his comrades had been buried in a mass grave near the town of Vallegrande in central Bolivia. In 1997 a skeleton that is believed be that of the revolutionary and the remains of his six comrades are disinterred and transported to Cuba to be interred in a massive memorial and monument in Santa Clara on the 30th anniversary of Guevara’s death. In 2007, a French and a Spanish journalist make a case that the body brought to Cuba is not actually Guevara’s. The Cuban government refutes the claim, citing scientific evidence from 1997 that, it says, proves that the remains are those of Guevara.

Guevara would live on as a powerful symbol, bigger in some ways in death than in life. He is almost always referenced simply as Che — like Elvis Presley, so popular an icon that his first name alone is identifier enough. Many on the political right condemn him as brutal, cruel, murderous, and all too willing to employ violence to reach revolutionary ends. On the other hand, his romanticized image as a revolutionary looms especially large for the generation of young leftist radicals in Western Europe and North America in the turbulent 1960s. Almost from the time of his death, his whiskered face adorns T-shirts and posters. Framed by a red-star-studded beret and long hair, his face frozen in a resolute expression, the iconic image is derived from a photo taken by Cuban photographer Alberto Korda on March 5, 1960, at a ceremony for those killed when a ship that had brought arms to Havana exploded. At first the image of Che is worn as a statement of rebellion, then as the epitome of radical chic, and, with the passage of time, as a kind of abstract logo whose original significance may even have been lost on its wearer, though for some he remains an enduring inspiration for revolutionary action.