Sir James Ware, historian, collector of manuscripts, and civil servant, dies at his home in Castle Street, Dublin, on December 1, 1666.

Ware is born on November 16, 1594, in Castle Street, Dublin, eldest surviving son among ten children of Sir James Ware, auditor general, and his wife Mary Bryden, sister of Sir Ambrose Briden of Maidstone, Kent, England, whose house provides Ware’s base in England. His father, a Yorkshireman, comes to Ireland in the train of Lord Deputy of Ireland Sir William FitzWilliam in 1588 and builds up a substantial landed estate. He enters Trinity College Dublin (TCD), where his father is the college auditor, as a fellow commoner in 1605 and is presented a silver standing bowl in 1609. His association with the college continues, as he particularly remembers the philosophy lectures of Anthony Martin, who becomes a fellow in 1611. He takes his MA on January 8, 1628, but by then he has already launched on his future course. His father procures him the reversion of his office in 1613, and by 1620 he already owns the Annals of Ulster and is taking notes from the Black Book of Christ Church. In 1621, he marries Elizabeth Newman, daughter of Jacob Newman, one of the six clerks in chancery. Newman becomes clerk of the rolls in 1629, which apparently facilitates Ware’s assiduous research in the Irish public records.

From Ware’s numerous surviving notebooks, it is possible to follow his scholarly tracks over the rest of his life. He is particularly concerned to trace the succession of the Irish bishops. The first fruits appear in print in 1626, Archiepiscoporum Cassiliensium et Tuamensium . . . adjicitur historia coenobiorum Cisterciensium Hiberniae, followed in 1628 by De presulibus Lageniae . . ., the whole to be rounded off in 1665 with De presulibus Hiberniae. . . . However, he has wide interests in Irish history and in 1633 edits Edmund Spenser‘s A View of the Present State of Irelande and the Irish histories of Edmund Campion, Meredith Hanmer, and Henry of Marlborough. The first Irish biographical dictionary follows in 1639, De scriptoribus Hiberniae. Both publications are dedicated to the viceroy, Thomas Wentworth. In public life he is a supporter, first of Wentworth, later of James Butler, 1st Duke of Ormond, rather than a leader, and always a stout royalist. He is knighted in 1630 and following his father’s death in 1632 he succeeds as auditor general. He is elected member of parliament for Dublin University in 1634, 1640, and 1661, but is not admitted to the Privy Council of Ireland until 1640.

Shortly after the outbreak of rebellion in October 1641, Ware is in England, and in London at the time of the passing of the Adventurers’ Act 1640, presumably on the council’s business. During Ormond’s prolonged negotiations with the confederates, he is sent to advise the king at Oxford in November 1645. While there he works in the Bodleian Library and is incorporated into the university as a Doctor of Civil Law. On his way back to Ireland in January 1646, he is captured at sea by a parliament ship and held prisoner in the Tower of London until October 1646.

When Ormond is arranging the surrender of Dublin to the parliament in the summer of 1647, Ware is sent to London as one of the hostages for his performance of the terms. Back in Dublin he has been replaced as auditor general but is able to carry on his work on the public records. In 1648 he publishes the catalogue of his manuscript library. As a leading royalist he is unwelcome to those governing the city for the parliament and is sent into exile in France on April 7, 1649, with his eldest son, also James, who already holds the reversion of the auditor generalship and eventually succeeds his father. He is allowed to live in London from October 1650, and from 1653, when hostilities end in Ireland, he is allowed brief visits there, perhaps taking up residence again in 1658.

Ware’s years in London are spent in the library of Archbishop of Armagh James Ussher, then in Lincoln’s Inn, and in the Royal, Cotton, Carew, and Dodsworth libraries. He publishes his De Hibernia et antiquitatibus ejus disquisitiones in 1654, lamenting the inaccessibility of his notes, then in Dublin. The second edition, published in 1658, also includes the annals of Henry VII. His Opuscula Sancto Patricio . . . adscripta . . . appears in 1656. In it he remarks that his knowledge of the Irish language is not expert enough for an edition of the ‘Lorica’. According to Roderick O’Flaherty, Ware can read and understand but not speak Irish. For the older language he employs Irish scholars, Dubhaltach Mac Fhirbhisigh being the last and most learned. The 1660 Stuart Restoration sees him back as auditor general and one of the commissioners for the Irish land settlement. He publishes annals of Henry VIII in 1662, and in 1664 annals for 1485–1558.

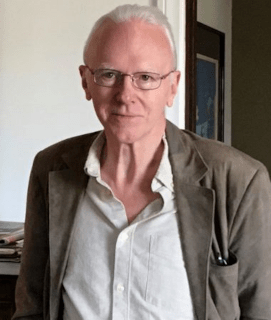

Ware dies in his house in Castle Street on December 1, 1666, and is buried in the family vault in St. Werburgh’s Church, Dublin. He has numerous friends among the scholars of the day, including Irish Franciscans, across the sectarian divide. While clergy lists are still partly dependent on his work, his notebooks and manuscripts remain of first importance for the study of medieval Ireland. Of his ten children, two boys and two girls survive him. His wife dies on June 9, 1651. The engraving by George Vertue prefixed to Harris’ edition of Ware’s Works is claimed to be based on a portrait in the possession of the family.

(From: “Ware, Sir James” by William O’Sullivan, Dictionary of Irish Biography, http://www.dib.ie, October 2009)