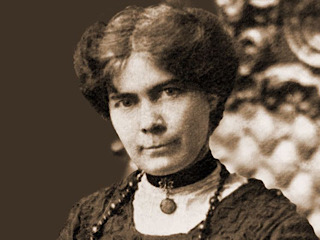

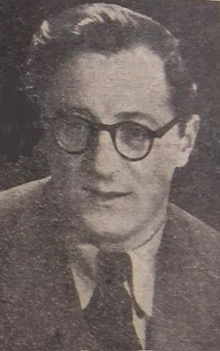

Éamon de Valera, Irish politician and patriot, is born George de Valero on October 14, 1882, in Lennox Hill, a neighborhood on the Upper East Side of Manhattan in New York City. He serves as Taoiseach (1932–48, 1951–54, 1957–59) and President of Ireland (1959–73). An active revolutionary from 1913, he becomes president of Sinn Féin in 1917 and founds the Fianna Fáil party in 1926. In 1937, he makes his country a sovereign state, renamed Ireland, or Éire. His academic attainments also inspire wide respect. He becomes chancellor of the National University of Ireland in 1921.

De Valera is the son of Catherine Coll, who is originally from Bruree, County Limerick, and Juan Vivion de Valera, described on the birth certificate as a Spanish artist born in 1853. His father dies when he is two years old. He Is then sent to his mother’s family in County Limerick, and studies at the local national school and at Blackrock College, Dublin. He graduates from the Royal University of Ireland and becomes a teacher of mathematics and an ardent supporter of the Irish language revival. In 1913, he joins the Irish Volunteers, which had been organized to resist opposition to Home Rule for Ireland.

In the 1916 Easter Rising in Dublin, de Valera commands an occupied building and is the last commander to surrender. Because of his American birth, he escapes execution by the British but is sentenced to penal servitude. Released in 1917 but arrested again and deported in May 1918 to England, where he is imprisoned, he is acclaimed by the Irish as the chief survivor of the uprising and in October 1917 is elected president of the Irish republican and democratic socialist Sinn Féin political party, which wins three-fourths of all the Irish constituencies in December 1918.

After a dramatic escape from HM Prison Lincoln in February 1919, de Valera goes in disguise to the United States, where he collects funds. He returns to Ireland before the Irish War of Independence ends with the truce that takes effect on July 11, 1921, and appoints plenipotentiaries to negotiate in London. He repudiates the Anglo-Irish Treaty of December 6, 1921, that they signed to form the Irish Free State, however, primarily because it imposes an oath of allegiance to the British crown.

After Dáil Éireann ratifies the treaty by a small majority in 1922, de Valera supports the republican resistance in the ensuing Irish Civil War. W. T. Cosgrave’s Irish Free State ministry imprisons him, but he is released in 1924 and then organizes a republican opposition party that does not sit in Dáil Éireann. In 1927, however, he persuades his followers to sign the oath of allegiance as “an empty political formula,” and his new Fianna Fáil (“Soldiers of Destiny”) party then enters the Dáil, demanding abolition of the oath of allegiance, of the governor-general, of the Seanad Éireann (senate) as then constituted, and of land-purchase annuities payable to Great Britain. The Cosgrave ministry is defeated by Fianna Fáil in 1932, and de Valera, as head of the new ministry, embarks quickly on severing connections with Great Britain. He withholds payment of the land annuities, and an “economic war” results. Increasing retaliation by both sides enables de Valera to develop his program of austere national self-sufficiency in an Irish-speaking Ireland while building up industries behind protective tariffs. In the new Constitution of Ireland, ratified by referendum in 1937, the Irish Free State becomes Ireland, a sovereign, independent democracy tenuously linked with the British Commonwealth (under the Executive Authority (External Relations) Act 1936) only for purposes of diplomatic representation.

De Valera’s prestige is enhanced by his success as president of the council of the League of Nations in 1932 and of its assembly in 1938. He also enters negotiations with British Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain in which he guarantees that he will never allow Ireland to be used as a base for attacking Britain in the event of war. This culminates in the Anglo-Irish defense agreement of April 1938, whereby Britain relinquishes the naval bases of Cobh, Berehaven, and Lough Swilly (retained in a defense annex to the 1921 treaty), and in complementary finance and trade treaties that end the economic war. This makes possible de Valera’s proclamation in September 1939, upon the outbreak of World War II, that Ireland will remain neutral and will resist attack from any quarter. In secret, however, de Valera also authorizes significant military and intelligence assistance to both the British and the Americans throughout the war. He realizes that a German victory will imperil Ireland’s independence, of which neutrality is the ultimate expression. By avoiding the burdens and destruction of the war, de Valera achieves a relative prosperity for Ireland in comparison with the war-torn countries of Europe, and he retains office in subsequent elections.

In 1948, a reaction against the long monopoly of power and patronage held by de Valera’s party enables the opposition, with the help of smaller parties, to form an interparty government under John A. Costello. Ironically, this precarious coalition collapses within three years after Ireland becomes a republic by means of the repeal of the Executive Authority (External Relations) Act 1936 and the severance of all ties with the British Commonwealth, an act de Valera had avoided. De Valera resumes office until 1954, when he appeals unsuccessfully for a fresh mandate, and Costello forms his second interparty ministry. No clearly defined difference now exists between the opposing parties in face of rising prices, continued emigration, and a backward agriculture. De Valera claims, however, that a strong single-party government is indispensable and that all coalitions must be weak and insecure. On this plea he obtains, in March 1957, the overall majority that he demands.

In 1959, de Valera agrees to stand as a candidate for the presidency. He resigns his position as Taoiseach and leader of the Fianna Fáil party. In June he is elected president, and is reelected in 1966. He retires to a nursing home near Dublin in 1973 and dies there on August 29, 1975.

De Valera’s career spans the dramatic period of Ireland’s modern cultural and national revolution. As an anticolonial leader, a skillful constitutionalist, and a symbol of national liberation, he dominates Ireland in the half century following the country’s independence.

(From: “Éamon de Valera, president of Ireland,” Encyclopedia Britannica, http://www.britannica.com, last updated August 14, 2025)