William Brown, Irish sailor, merchant, and naval commander who serves in the Argentine Navy during the wars of the early 19th century, is born on June 22, 1777, in Foxford, County Mayo. He is also known in Spanish as Guillermo Brown or Almirante Brown.

Comparatively little is known of his early life, and it has been suggested that he was illegitimate and took his mother’s surname and that his father’s surname was actually Gannon. He emigrates with his father to Baltimore, Maryland, in 1793, eventually settling in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. A short time after their arrival, the friend who had invited them and offered them food and hospitality dies of yellow fever. Several days later, his father also succumbs to the same disease.

One morning, while Brown is wandering along the banks of the Delaware River, he meets the captain of a ship then moored in port. The captain inquires if he wants employment and Brown agrees. The captain engages him as a cabin boy, thereby setting him on the naval promotion ladder, where he works his way to the captaincy of a merchant ship. After ten years at sea, where he develops his skills as a sailor and reaches the rank of captain, Brown is press-ganged into a Royal Navy warship. British impressment of American sailors is one of the primary issues leading to the War of 1812.

During the Napoleonic Wars, Brown escapes the ship he is serving on, a galley, and scuttles the vessel. However, the French do not believe he had assisted them and imprison him in Lorient. On being transferred to Metz, he escapes, disguised in a French officer’s uniform. However, he is recaptured and is imprisoned in the fortress of Verdun. In 1809, he escapes from there in the company of a British Army officer named Clutchwell, and eventually reaches German territory.

Returning to England, Brown renounces his maritime career and on July 29, 1809, he marries Elizabeth Chitty, daughter of an English shipping magnate, in Kent. As he is a Catholic and she a Protestant, they agree to raise their sons as Catholics and their daughters as Protestants. Despite lengthy periods of enforced separation, they have nine children. He leaves the same year for the Río de la Plata on board Belmond and sets himself up as a merchant in Montevideo, Uruguay.

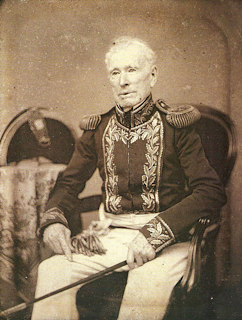

Late in 1811 Brown settles in Buenos Aires just as a criollo rebellion against Spanish colonial rule in Argentina is gaining strength. By April 1812, he is developing a coastal shipping business in fruit and hides. As the Spanish naval blockade of 1812–14 begins to choke trade, he is first commissioned by the patriot government as a privateer licensed to raid Spanish merchantmen, and then, on March 1, 1814, invited to take charge of a small rebel naval squadron to contest Spanish control of the Río de la Plata estuary. Leading a fleet of nineteen ships, he fixes with great speed on a set of wartime naval routines and signaling methods, and organises a system of discipline, founding the navy on principles that pay exceptional attention to the welfare of ordinary seamen.

In early March 1814, Brown shows personal courage and incisive skill in outwitting and defeating a more powerful Spanish force near Martín García Island, thereby dividing the Spanish blockade. A Spanish attempt in May 1814 to break his blockade of Montevideo is decisively crushed by him and his makeshift navy, and the Spanish strongholds on the Atlantic coast collapse, ending open war. In 1815 and 1816, however, he carries out skirmishing raids on military and commercial targets belonging to Spanish South American possessions, until detained by a British colonial governor in Barbados in July 1816 for alleged infringements of international rules of trade.

Illness, and a tortuous but ultimately successful appeal process, take up most of 1817–18, but when Brown returns to Argentina in October 1818, political enemies set in motion a prosecution for alleged disobedience of orders. Cashiered in August 1819, then restored in rank but forced to retire, he attempts suicide the following month. Convalescence and resumption of his trading concern occupies him for several years.

A repentant government renews Brown’s command of the navy in December 1825, when war breaks out with Brazil. Though vastly outnumbered by the Brazilian fleet, he shows audacity and great finesse in a number of successful engagements in the Plate estuary in 1826, roving up the Brazilian coast on occasion to create great confusion. In February 1827, he triumphs in a series of actions known as the Battle of Juncal. After another year of commercial privateering against the Brazilian merchant fleet, he is one of two delegates selected to sign peace terms with Brazil in October 1828.

Retiring from active service that month, Brown tries to remain neutral as civil war erupts in Argentina, but reluctantly accepts the post of governor of Buenos Aires under General Juan Lavalle from December 1828 to May 1829, when he resigns in disgust at government excesses. During 1829–37 he holds aloof from the despotic government of Juan Manuel de Rosas. After French and British encroachments on the region in the later 1830s, he offers to take charge of the navy again to protect national independence and is available to defend Argentine interests when war breaks out with a French-backed Uruguay in early 1841. Though exasperated by a long and “stupid war,” he blockades the Uruguayan navy effectively until French and British fleets intervene in July 1845 with overwhelming force to capture his squadron and bring the war to an end.

Idolised by the Argentinian population for his high-principled and humane advocacy of independent democracy, Brown passes his last years trading and farming a country estate. In late 1847, he journeys to Ireland, hoping to find relations in Mayo, and is shocked by the hunger and destitution of the Great Famine.

Brown dies on March 3, 1857, at his home in Buenos Aires and is buried with full military honours. The Argentine government issues a comuniqué: “With a life of permanent service to the national wars that our homeland has fought since its independence, William Brown symbolized the naval glory of the Argentine Republic.” During his burial, General Bartolomé Mitre famously says: “Brown in his lifetime, standing on the quarterdeck of his ship, was worth a fleet to us.” His grave is currently located in the La Recoleta Cemetery in Buenos Aires.