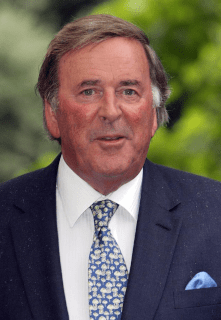

John Gerard Bruton, Irish Fine Gael politician who serves as Taoiseach from 1994 to 1997 and Leader of Fine Gael from 1990 to 2001, is born to a wealthy, Catholic farming family in Dunboyne, County Meath, on May 18, 1947. He plays a crucial role in advancing the process that leads to the Good Friday Agreement in 1998.

Bruton is educated at Clongowes Wood College and then goes on to study economics at University College Dublin (UCD), where he receives an honours Bachelor of Arts degree and qualifies as a barrister from King’s Inns, but never goes on to practice law. He joins the Fine Gael party in 1965 and is narrowly elected to Dáil Éireann in the 1969 Irish general election, as a Fine Gael TD for Meath. At the age of 22, he is one of the youngest ever members of the Dáil at the time. He serves as a parliamentary secretary in the government of Liam Cosgrave (1973–77).

Following Fine Gael’s defeat at the 1977 Irish general election, the new leader, Garret FitzGerald, appoints Bruton to the front bench as Spokesperson on Agriculture. He is later promoted as Spokesperson for Finance. He plays a prominent role in Fine Gael’s campaign in the 1981 Irish general election, which results in another coalition with the Labour Party, with FitzGerald as Taoiseach. He receives a personal vote in Meath of nearly 23%, and at the age of only 34 is appointed Minister for Finance, the most senior position in the cabinet. In light of overwhelming economic realities, the government abandons its election promises to cut taxes. The government collapses unexpectedly on the night of January 27, 1982, when Bruton’s budget, that was to impose an unpopular value-added tax (VAT) on children’s shoes, is defeated in the Dáil.

The minority Fianna Fáil government which follows only lasts until November 1982, when Fine Gael once again returns to power in a coalition government with the Labour Party. However, when the new government is formed, Bruton is moved from Finance to become Minister for Industry and Energy. After a reconfiguration of government departments in 1983, he becomes Minister for Industry, Trade, Commerce and Tourism. In a cabinet reshuffle in February 1986, he is appointed again as Minister for Finance. Although he is Minister for Finance, he never presents his budget. The Labour Party withdraws from the government due to a disagreement over his budget proposals leading to the collapse of the government and another election.

Following the 1987 Irish general election, Fine Gael suffers a heavy defeat. Garret FitzGerald resigns as leader immediately, and a leadership contest ensues between Alan Dukes, Peter Barry and Bruton himself, with Dukes being the ultimate victor. Dukes’s term as leader is lackluster and unpopular. The party’s disastrous performance in the 1990 Irish presidential election, in which the party finishes in a humiliating and then unprecedented third in a national election, proves to be the final straw for the party and Dukes is forced to resign as leader shortly thereafter. Bruton, who is the deputy leader of Fine Gael at the time, is unopposed in the ensuing leadership election.

Bruton’s election is seen as offering Fine Gael a chance to rebuild under a far more politically experienced leader. However, his perceived right-wing persona and his rural background are used against him by critics and particularly by the media. However, to the surprise of critics and of conservatives, in his first policy initiative he calls for a referendum on a Constitutional amendment permitting the enactment of legislation allowing for divorce in Ireland.

By the 1992 Irish general election, the anti-Fianna Fáil mood in the country produces a major swing to the opposition, but that support goes to the Labour Party, not Bruton’s Fine Gael, which actually loses a further 10 seats. Even then, it initially appears that Fine Gael is in a position to form a government. However, negotiations stall in part from Labour’s refusal to be part of a coalition which would include the libertarian Progressive Democrats, as well as Bruton’s unwillingness to take Democratic Left into a prospective coalition. The Labour Party breaks off talks with Fine Gael and opts to enter a new coalition with Fianna Fáil.

In late 1994, the government of Fianna Fáil’s Albert Reynolds collapses. Bruton is able to persuade Labour to end its coalition with Fianna Fáil and enter a new coalition government with Fine Gael and Democratic Left. He faces charges of hypocrisy for agreeing to enter government with Democratic Left, as Fine Gael campaigned in the 1992 Irish general election on a promise not to enter government with the party. Nevertheless, on December 15, 1994, aged 47, he becomes the then youngest ever Taoiseach. This is the first time in the history of the state that a new government is installed without a general election being held.

Bruton’s politics are markedly different from most Irish leaders. Whereas most leaders had come from or identified with the independence movement Sinn Féin (in its 1917–22 phase), Bruton identifies more with the more moderate Irish Parliamentary Party (IPP) tradition that Sinn Féin had eclipsed at the 1918 Irish general election.

Continued developments in the Northern Ireland peace process and Bruton’s attitude to Anglo-Irish relations come to define his tenure as Taoiseach. In February 1995, he launches the Anglo-Irish “Framework Document” with the British prime minister John Major. It foreshadows the 1998 Good Friday Agreement, which, among other things, establishes an elected, power-sharing executive authority to be run by these onetime adversaries, ending 30 years of bloodletting that had claimed more than 3,000 lives. However, he takes a strongly critical position on the British Government‘s reluctance to engage with Sinn Féin during the Irish Republican Army‘s 1994–1997 ceasefire. He also establishes a working relationship with Gerry Adams of Sinn Féin; however, both are mutually distrustful of each other.

Bruton presides over a successful Irish Presidency of the European Union in 1996, and helps finalise the Stability and Growth Pact, which establishes macroeconomic parameters for countries participating in the single European currency, the euro. He is the fifth Irish leader to address a joint session of the United States Congress on September 11, 1996. He presides over the first official visit by a member of the British royal family since 1912, by Charles, Prince of Wales.

The coalition remains in force to contest the 1997 Irish general elections, which are indecisive, and Bruton serves as acting taoiseach until the Dáil convenes in late June and elects a Fianna Fáil–Progressive Democrats government. He retires from Irish politics in 2004 and serves as the European Union Ambassador to the United States (2004–09).

Bruton dies at the age of 76 on February 6, 2024, at the Mater Private Hospital in Dublin, following a long bout with cancer. A state funeral is held on February 10 at St. Peter’s and St. Paul’s Church in Dunboyne.