Frank J. (Francis John) Fay, actor, theatrical producer and co-founder of the Abbey Theatre in Dublin, dies on January 2, 1931.

Fay is born on August 30, 1870, at 10 Lower Dorset Street, Dublin, the eldest son of four children of William Patrick Fay, a government clerk, and his wife, Martha Fay (née Dowling). He is educated at Belvedere College, Dublin, where he learns shorthand and typing, before leaving to become a secretary for an accountancy firm in Dublin. From an early age he has a passion for the theatre and immerses himself in books on the subject, becoming a drama expert. His brother, William George Fay, shares his enthusiasm and they take part in many amateur productions, setting up the Ormonde Dramatic Company in 1891.

Fay is an ardent nationalist, and Arthur Griffith appoints him drama critic for his newspaper, the United Irishman (1899–1902), where he develops his ideas on how the theatre should be run. Initially in favour of plays in the Irish language, he soon abandons this as unworkable. In May 1901 he attacks W. B. Yeats for his faulty notions about theatre and even his work as a dramatist, ending with the fiercely nationalistic assertion that “there is a herd of Saxon and other swine fattening on us. They must be swept into the sea with the pestilent breed of West Britons with which we are troubled, or they will sweep us there.” Yeats’s and Lady Gregory‘s next play is Cathleen ni Houlihan.

In 1902, Fay writes a famous article advocating a national theatre company that will “be the nursery of an Irish dramatic literature which, while making a world-wide appeal, would see life through Irish eyes.” He is a member of his brother’s National Dramatic Society, which merges with the Irish Literary Theatre in 1902 to form the Irish National Theatre Society, the originating body of the Abbey Theatre. The following year Yeats declares that the national theatre owes its existence to the two Fay brothers. Fay soon abandons Griffith and begins to champion the cause of Yeats.

An excellent tragic actor, Fay can make audiences forget his less than five feet six-inch stature through the power of his voice. When the Abbey Theatre opens on December 27, 1904, he stars in Yeats’s On Baile’s Strand as Cú Chulainn, a role he makes his own. He spends much time training the other actors. As an elocution teacher he has no equal. One play has Yeats leaving with his “head on fire” because of the quality of the voices on stage. Yeats dedicates his play The King’s Threshold (1904) with the words: “In memory of Frank Fay and his beautiful speaking in the character of Seanchan.”

Fay has a close but turbulent relationship with his brother William, whom he defers to in all theatrical matters except acting. Their heated arguments sometimes lead to blows. His temper is always volatile, and he is prone to histrionics and fits of depression. After 1905, the Abbey Theatre becomes a limited company owing to the patronage of Annie Horniman, and the Fays lose most of their control, which results in much tension and bitterness. In 1907, Fay plays Shawn Keogh in the first production of The Playboy of the Western World by John Millington Synge.

Disagreements with Yeats over the approach to choosing and staging of plays comes to a head late in late 1907 and the Fays resign on January 13, 1908. On March 13 they are suspended from the Irish National Theatre Society. They tour the United States with Charles Frohman before separating. Fay then tours England in minor Shakespearean roles and melodrama. Between 1912 and 1914, Thomas MacDonagh and Joseph Mary Plunkett attempt to persuade him to become actor-manager of an Irish theatre. In 1918 he returns to the Abbey Theatre in two short-lived revivals of Yeats’s The Hour Glass and The King’s Threshold. He retires to Dublin permanently in 1921, teaching elocution and directing plays in local colleges.

Fay marries, in 1912, Freda, known as “Bird.” They live at Upper Mount Street, Dublin, and have one son, Gerard, who becomes a popular writer and memoirist. Fay dies on January 2, 1931, having never really recovered from the death of his wife, and is buried at Glasnevin Cemetery. He is credited with creating the Abbey Theatre style of acting, which becomes internationally known, and influences many other schools of acting. He wanted actors to behave as naturally as possible and to speak the lines as people would in real life, rather than with an exaggerated stage delivery. His training is a major influence on subsequent generations, as actors learned to “speak words with quiet force, like feathers borne on puffs of wind.”

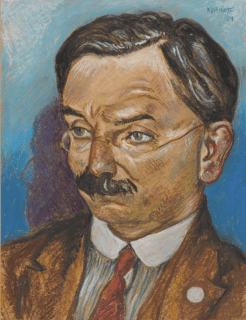

(From: “Fay, Frank J. (Francis John)” by Patrick M. Geoghegan, Dictionary of Irish Biography, http://www.dib.ie, October 2009) | Pictured: Portrait of Frank Fay by John Butler Yeats, commissioned by Annie Horniman for the opening of the Abbey Theatre, December 27, 1904)