The Dunmanway killings, also known as the Dunmanway murders or the Dunmanway massacre, takes place in and around Dunmanway, County Cork between April 26-28, 1922. The event refers to the killing (and in some cases, disappearances) of thirteen Protestant men and boys.

The killings happen in a period of truce after the July 1921 end of the Irish War of Independence and before the outbreak of the Irish Civil War in June 1922. All the dead and missing are Protestants, which has led to the killings being described as sectarian. Six are killed as purported British informants and loyalists, while four others are relatives killed in the absence of the target. Three other men are kidnapped and executed in Bandon as revenge for the killing of an Irish Republican Army (IRA) officer Michael O’Neill during an armed raid. One man is shot and survives his injuries.

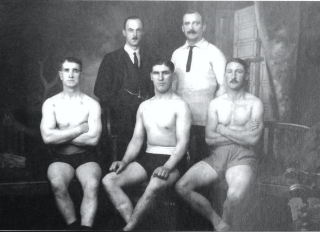

On April 26, 1922, a group of anti-Treaty IRA men, led by Michael O’Neill, arrive at the house of Thomas Hornibrook, a former magistrate, at Ballygroman, East Muskerry, Desertmore, Bandon (near Ballincollig on the outskirts of Cork City), seeking to seize his car. Hornibrook is in the house at the time along with his son, Samuel, and his nephew, Herbert Woods, a former Captain in the British Army. O’Neill demands a part of the engine mechanism that had been removed by Hornibrook to prevent such theft. Hornibrook refuses to give them the part, and after further efforts, some of the IRA party enter through a window. Herbert Woods then shoots O’Neill, wounding him fatally. O’Neill’s companion, Charlie O’Donoghue, takes him to a local priest who pronounces him dead. The next morning O’Donoghue leaves for Bandon to report the incident to his superiors, returning with “four military men,” meeting with the Hornibrooks and Woods, who admit to shooting O’Neill.

It is not clear who orders the attacks or carries them out. However, in 2014 The Irish Times releases a confidential memo from the then-Director of Intelligence Colonel Michael Joe Costello (later managing director of the Irish Sugar Company) in September 1925 in relation to a pension claim by former IRA volunteer Daniel O’Neill of Enniskeane, County Cork, stating: “O’Neill is stated to be a very unscrupulous individual and to have taken part in such operations as lotting [looting] of Post Offices, robbing of Postmen and the murder of several Protestants in West Cork in May 1922. A brother of his was shot dead by two of the latter named, Woods and Hornbrooke [sic], who were subsequently murdered.”

Sinn Féin and IRA representatives, from both the pro-Treaty side, which controls the Provisional Government in Dublin and the anti-Treaty side, which controls the area the killings take place in, immediately condemn the killings.

The motivation of the killers remains unclear. It is generally agreed that they were provoked by the fatal shooting of O’Neill by Woods, whose house was being raided on April 26. Some historians have claimed there were sectarian motives; others claim that those killed were targeted only because they were suspected of having been informers during the Irish War of Independence and argue that the dead were associated with the so-called “Murragh Loyalist Action Group,” and that their names may have appeared in captured British military intelligence files which listed “helpful citizens” during the war.

(Pictured: Herbert Woods, centre, whose decision to shoot sparks the massacre)