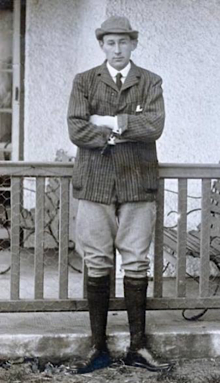

Sir Anthony Brutus Babington PC (NI), Anglo-Irish barrister, judge and politician, is born on November 24, 1877, at Creevagh House, County Londonderry, to Hume Babington JP, son of Rev. Hume Babington and a landowner of 1,540 acres, and Hester (née Watt), sister of Andrew Alexander Watt.

Babington is born into the Anglo-Irish Babington family that arrives in Ireland in 1610 when Brutus Babington is appointed Bishop of Derry. Notable relations include Robert Babington, William Babington, Benjamin Guy Babington and James Melville Babington and author Anthony Babington.

Babington is educated at Glenalmond School, Perthshire, and Trinity College, Dublin, where he wins the Gold Medal for Oratory of the College Historical Society in 1899.

Babington is called to the Irish Bar in 1900. He briefly lectures in Equity at King’s Inns, and it is during this time, in 1910, that he re-arranges and re-writes R.E. Osborne’s Jurisdiction and Practice of County Courts in Ireland in Equity and Probate Matters. He takes silk in 1917.

Babington moves to the newly established Northern Ireland in 1921 and practises as a barrister until his election to the House of Commons of Northern Ireland as the Ulster Unionist Party member for Belfast South in the 1925 Northern Ireland general election and subsequent appointment as Attorney General for Northern Ireland the same year in the cabinet of James Craig, 1st Viscount Craigavon. His appointment to the Privy Council of Northern Ireland in 1926 entitles him to the style “The Right Honourable.” From 1929 he is the MP for Belfast Cromac, the Belfast South constituency having been abolished. He is made an honorary bencher of the Middle Temple in 1930.

Babington resigns from politics in 1937 upon his appointment as a Lord Justice of Appeal and is knighted in the 1937 Coronation Honours.

In 1947, Babington chairs the Babington Agricultural Enquiry Committee, named in his honour, which is established in 1943 to examine agriculture in Northern Ireland. The committee’s first recommendation under Babington’s leadership is that Northern Ireland should direct all its energies to the production of livestock and livestock products and to their efficient processing and marketing.

Babington retires from the judiciary in 1949, taking up the chairmanship of the Northern Ireland Transport Tribunal, which exists until 1967, established under the Ulster Transport Act – promoting a car-centred transport policy – and which is largely responsible for the closure of the Belfast and County Down Railway. He endorses the closure on financial grounds and is at cross purposes with his co-chair, Dr. James Beddy, who advises against the closure, citing the disruption of life in the border region between the north and the south as his primary reason in addition to financial grounds.

Babington also chairs a government inquiry into the licensing of clubs, the proceeds of which results in new regulatory legislation at Stormont. While Attorney General, he is a proponent of renaming Northern Ireland as “Ulster.”

Babington is critical of the newly proposed Irish constitution, in which the name of the Irish state is changed to “Ireland,” laying claim to jurisdiction over Northern Ireland.

Michael McDunphy, Secretary to the President of Ireland, then Douglas Hyde, recalls Ernest Alton‘s correspondence with Babington on the question of Irish unity, in which Alton and Babington are revealed to be at cross purposes. The discussion is used as an example by Brian Murphy, in Forgotten Patriot: Douglas Hyde and the Foundation of the Irish Presidency, as an example of the office of the Irish President becoming embroiled in an initiative involving Trinity College Dublin and a senior Northern Ireland legal figure, namely Babington.

Babington writes to Alton, then Provost of Trinity College, Dublin, expressing his view that, as Murphy summarises, “… Severance between the two parts of Ireland could not continue, that it was the duty of all Irishmen to work for early unification and that in his opinion Trinity College was a very appropriate place in which the first move should be made.” When Alton arrives to meet with Hyde, it emerges, after conversing with Hyde’s secretary McDunphy, that he and Babington are at cross purposes. “It soon became clear that the united Ireland contemplated by Mr. [sic] Justice Babington of the Northern Ireland Judiciary was one within the framework of the British Commonwealth of Nations, involving recognition of the King of England as the Supreme Head, or as Dr. Alton put it, the symbol of unity of the whole system,” writes McDunphy.

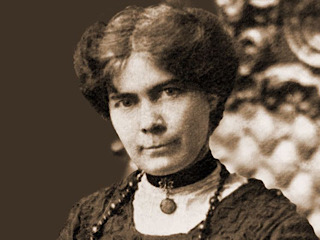

On September 5, 1907, Babington marries Ethel Vaughan Hart, daughter of George Vaughan Hart of Howth, County Dublin (the son of Sir Andrew Searle Hart) and his wife Mary Elizabeth Hone, a scion of the Hone family. They have three children.

Babington is a member of the Apprentice Boys of Derry. From 1926 to 1952, he is a member of the board of governors of the Belfast Royal Academy. He serves as warden (chairman) of the board from 1941 to 1943. Through his efforts the school acquires the Castle Grounds from Anthony Ashley-Cooper, 9th Earl of Shaftesbury in 1934.

Babington is a keen golfer. He is an international golfer from 1903 to 1913, during which he is runner-up in the Irish Amateur Golf Championships in 1909 and one of the Irish representatives at an international match in 1913. The Babington Room in the Royal Portrush Golf Club is named after him, as is the 18th hole on the course as a result of the key role he plays in shaping its history.

Babington dies at the age of 94 on April 10, 1972 at his home, Creevagh, Portrush, County Antrim.