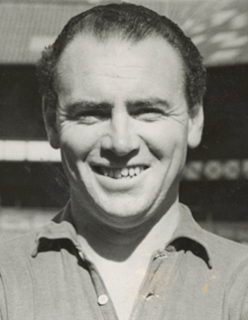

Richard James Mulcahy, Irish Fine Gael politician and army general, is born in Manor Street, Waterford, County Waterford, on May 10, 1886, the son of post office clerk Patrick Mulcahy and Elizabeth Slattery. He is educated at Mount Sion Christian Brothers School and later in Thurles, County Tipperary, where his father is the postmaster.

Mulcahy joins the Royal Mail (Post Office Engineering Dept.) in 1902, and works in Thurles, Bantry, Wexford and Dublin. He is a member of the Gaelic League and joins the Irish Volunteers at the time of their formation in 1913. He is also a member of the Irish Republican Brotherhood.

Mulcahy is second-in-command to Thomas Ashe in an encounter with the armed Royal Irish Constabulary (RIC) at Ashbourne, County Meath, during the 1916 Easter Rising, one of the few stand-out victories won by republicans in that week and generally credited to Mulcahy’s grasp of tactics. In his book on the Rising, Charles Townshend principally credits Mulcahy with the defeat of the RIC at Ashbourne, for conceiving and leading a flanking movement on the RIC column that had engaged with the Irish Volunteers. Arrested after the Rising, he is interned at Knutsford and at the Frongoch internment camp in Wales until his release on December 24, 1916.

On his release, Mulcahy immediately rejoins the republican movement and becomes commandant of the Dublin Brigade of the Irish Volunteers. He is elected to the First Dáil in the 1918 Irish general election for Dublin Clontarf. He is then named Minister for Defence in the new government and later Assistant Minister for Defence. In March 1918, he becomes Irish Republican Army (IRA) chief of staff, a position he holds until January 1922.

Mulcahy and Michael Collins are largely responsible for directing the military campaign against the British during the Irish War of Independence. During this period of upheaval in 1919, he marries Mary Josephine (Min) Ryan, sister of Kate and Phyllis Ryan, the successive wives of Seán T. O’Kelly. Her brother is James Ryan. O’Kelly and Ryan both later serve in Fianna Fáil governments.

Mulcahy supports the Anglo-Irish Treaty of December 1921. Archive film shows that Mulcahy, as Minister of Defence, is the Irish officer who raises the Irish tricolour at the first hand-over of a British barracks to the National Army in January 1922. He is defence minister in the Provisional Government on its creation and succeeds Collins, after the latter’s assassination, as Commander-in-Chief of the Provisional Government’s forces during the subsequent Irish Civil War.

Mulcahy earns notoriety through his order that anti-Treaty activists captured carrying arms are liable for execution. A total of 77 anti-Treaty prisoners are executed by the Provisional Government. He serves as Minister for Defence in the new Free State government from January 1924 until March 1924, but resigns in protest because of the sacking of the Army Council after criticism by the Executive Council over the handling of the “Army Mutiny,” when some National Army War of Independence officers almost revolt after he demobilises many of them at the end of the Irish Civil War. He re-enters the cabinet as Minister for Local Government and Public Health in 1927.

During Mulcahy’s period on the backbenches of Dáil Éireann his electoral record fluctuates. He is elected as TD for Dublin North-West at the 1921 and 1922 Irish general elections. He moves to Dublin North for the election the following year and is re-elected there in four further elections: June 1927, September 1927, 1932, and 1933.

Dublin North is abolished for the 1937 Irish general election, at which Mulcahy is defeated in the new constituency of Dublin North-East. However, he secures election to Seanad Éireann as a Senator, the upper house of the Oireachtas, representing the Administrative Panel. The 2nd Seanad sits for less than two months, and at the 1938 Irish general election he is elected to the 10th Dáil as a TD for Dublin North-East. Defeated again in the 1943 Irish general election, he secures election to the 4th Seanad by the Labour Panel.

After the resignation of W. T. Cosgrave as Leader of Fine Gael in 1944, Mulcahy becomes party leader while still a member of the Seanad. Thomas F. O’Higgins is parliamentary leader of the party in the Dáil at the time and Leader of the Opposition. Facing his first general election as party leader, Mulcahy draws up a list of 13 young candidates to contest seats for Fine Gael. Of the eight who run, four are elected. He is returned again to the 12th Dáil as a TD for Tipperary at the 1944 Irish general election. While Fine Gael’s decline had been slowed, its future is still in doubt.

Following the 1948 Irish general election Mulcahy is elected for Tipperary South, but the dominant Fianna Fáil party finishes six seats short of a majority. However, it is 37 seats ahead of Fine Gael, and conventional wisdom suggests that Fianna Fáil is the only party that can possibly form a government. Just as negotiations get underway, however, Mulcahy realises that if Fine Gael, the Labour Party, the National Labour Party, Clann na Poblachta and Clann na Talmhan band together, they would have only one seat fewer than Fianna Fáil and, if they can get support from seven independents, they will be able to form a government. He plays a leading role in persuading the other parties to put aside their differences and join forces to consign the then Taoiseach and Fianna Fáil leader Éamon de Valera, to the opposition benches.

Mulcahy initially seems set to become Taoiseach in a coalition government. However, he is not acceptable to Clann na Poblachta’s leader, Seán MacBride. Many Irish republicans had never forgiven him for his role in the Irish Civil War executions carried out under the Cosgrave government in the 1920s. Consequently, MacBride lets it be known that he and his party will not serve under Mulcahy. Without Clann na Poblachta, the other parties would have 57 seats between them — 17 seats short of a majority in the 147-seat Dáil. According to Mulcahy, the suggestion that another person serve as Taoiseach comes from Labour leader William Norton. He steps aside and encourages his party colleague John A. Costello, a former Attorney General of Ireland, to become the parliamentary leader of Fine Gael and the coalition’s candidate for Taoiseach. For the next decade, Costello serves as the party’s parliamentary leader while Mulcahy remained the nominal leader of the party.

Mulcahy goes on to serve as Minister for Education under Costello from 1948 until 1951. Another coalition government comes to power at the 1954 Irish general election, with Mulcahy once again stepping aside to become Minister for Education in the Second Inter-Party Government. The government falls in 1957, but he remains as Fine Gael leader until October 1959. In October the following year, he tells his Tipperary constituents that he does not intend to contest the next election.

Mulcahy dies from natural causes at the age of 85 in Dublin on December 16, 1971. He is buried in Littleton, County Tipperary.